I am accepting charitable donations,.

ETH: 0x66e2871ef39334962fb75ce34407f825d67ec434 | BTC: 38B6vGaqNvMyTtoFEZPmNvMS7icV6ZnPMm | xDAI: 0x66e2871ef39334962fb75ce34407f825d67ec434

Tecumseh

| Tecumseh | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Chief of Tecumseh's Confederacy | |

| In office 1808 – October 5, 1813 |

|

| Preceded by | Tenskwatawa |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Chief of the Shawnee | |

| In office 1789 – October 5, 1813 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 1768 Likely on the Scioto River, near present-day Chillicothe, Ohio |

| Died | October 5, 1813 (aged 45) Moravian of the Thames, Upper Canada, British Empire |

| Resting place | Unknown,[1] (possibly Walpole Island, Ontario) |

| Nationality | Shawnee |

| Parents | Puckshinwa, Methoataske |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Western Confederacy Tecumseh's Confederacy |

| Years of service | 1783–1813 |

| Rank | Commander-in-chief (de-facto) |

| Battles/wars | Northwest Indian War Tecumseh's War War of 1812 † |

Tecumseh /tɪˈkʌmsə, tɪˈkʌmsi/ ti-KUM-sə, ti-KUM-see (March 1768 – October 5, 1813) was a Native American Shawnee warrior and chief, who became the primary leader of a large, multi-tribal confederacy in the early years of the nineteenth century. Born in the Ohio Country (present-day Ohio), and growing up during the American Revolutionary War and the Northwest Indian War, Tecumseh was exposed to warfare and envisioned the establishment of an independent Indian nation east of the Mississippi River under British protection and worked to recruit additional members to his tribal confederacy from the southern United States.[2]

Tecumseh was among the most celebrated Indian leaders in history and was known as a strong and eloquent orator who promoted tribal unity. He was also ambitious, willing to take risks, and make significant sacrifices to repel the Americans from Indian lands in the Old Northwest Territory. In 1808, with his brother Tenskwatawa ("The Prophet"), Tecumseh founded the Indian village the Americans called Prophetstown, located north of present-day Lafayette, Indiana. Prophetstown grew into a large, multi-tribal community and a central point in Tecumseh's political and military alliance.

Tecumseh's confederation fought the Americans during Tecumseh's War, but he was unsuccessful in getting the U.S. government to rescind the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809) and other land-cession treaties. In 1811, as he traveled south to recruit more allies, his brother Tenskwatawa initiated the Battle of Tippecanoe against William Henry Harrison's army, but the Indians retreated from the field and the Americans burned Prophetstown. Although Tecumseh remained the military leader of the pan-Indian confederation, his plan to enlarge the Indian alliance was never fulfilled.

Tecumseh and his confederacy continued to fight the Americans after forming an alliance with Great Britain in the War of 1812. During the war, Tecumseh's confederacy helped in the capture of Fort Detroit. However, after U.S. naval forces took control of Lake Erie in 1813, the British and their Indian allies retreated into Upper Canada, where the American forces engaged them at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813, and Tecumseh was killed. His death and the end of the war caused the pan-Indian alliance to collapse in failure. Within a few years, the remaining tribal lands in the Old Northwest were ceded to the U.S. government and subsequently opened for new settlement and most of the American Indians eventually moved west, across the Mississippi River. Since his death Tecumseh has become an iconic folk hero in American, Aboriginal and Canadian history.[3]

Early life and family background[edit]

Tecumseh (in Shawnee, Tekoomsē, meaning "Shooting Star" or "Panther Across The Sky", or "Blazing Comet," and also written as Tecumtha or Tekamthi) was born about March 1768.[4] Some accounts identify his birthplace as Old Chillicothe[5] (the present-day Oldtown area of Xenia Township, Greene County, Ohio, about 12 miles (19 km) east of Dayton). Because the Shawnee did not settle in Old Chillicothe until 1774, biographer John Sugden concludes that Tecumseh was born either in a different village named "Chillicothe" (in Shawnee, Chalahgawtha)[6] along the Scioto River, near present-day Chillicothe, Ohio, or in a nearby Kispoko village situated along a small tributary of the Scioto. (Tecumseh's family had moved to this village around the time of his birth.)[7]

Tecumseh's father, Puckshinwa (in Shawnee, Puckeshinwau), meaning "Alights from flying," "Something that drops," or "I light from flying," and rendered in various records as Puckeshinwa, Pucksinwah, Pukshinwa, Pukeesheno, Pekishinoah, Pooksehnwe and other variations) was a minor Shawnee war chief of the Kispoko ("Dancing Tail" or "Panther") band and the panther clan. According to some sources, Puckshinwa's father was Muscogee (Creek) and his mother was Shawnee. (Either his father died when Puckshinwa was young or because among the Creeks a husband lives with his wife's family, Puckshinwa was considered a Shawnee.)[8][9] Tecumseh biographer John Sugden concludes that Puckshinwa's ancestry "must remain a mystery," because other testimonies provide alternate details of his heritage, such as stating that said the Kispoko chief had a British father.[10][11]

Tecumseh's mother, Methotaske (in Shawnee, Methoataaskee, meaning "[One who] Lays Eggs in the Sand" or "A turtle laying eggs in the sand", and alternately spelled Methoataske, Meetheetashe, Methotase, or Methoatase), was Puckshinwa's second wife. She is believed to have been either either Muscogee Creek, Cherokee, or Shawnee through both her parents, possibly of the Pekowi band and the turtle clan. Some traditions argue that Methotaske was Creek because she had lived among that tribe prior to marriage, while others claim that she was Cherokee, having died in old age living among that tribe. Others suggest that she was a white captive due to the family stories that claim Puckshinwa had been married to a white captive.[8][12] Puckshinwa and Methotaske had at least eight children.[13] Shawnee divisional identity was recorded patrilineally, meaning that inheritance and descent are traced through the male line, which made Tecumseh and his siblings members of the Kispoko.[14] Tecumseh's great-great grandfather on his mother's side, Straight Tail Meaurroway Opessa, was a prominent chief of the Pekowi and the turtle clan.

When Tecumseh's parents met and married, the Pekowi were living somewhere near the present-day site of Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The Pekowi had lived in that region alongside the Creek people, since the Iroquois (a powerful confederacy based in New York and Pennsylvania) forced them from the Ohio River valley during the Beaver Wars in the seventeenth century.[15] About 1759 the Pekowi band moved north into the Ohio Country. Not wanting to force Methotaske to choose between staying in the south with him or moving with her family, Puckshinwa decided to travel north with her. The Pekowi founded an Indian settlement named Chillicothe, where Tecumseh was likely born.[16]

In October 1774, during Tecumseh's boyhood, frontiersmen killed his father at the Battle of Point Pleasant during Lord Dunmore’s War.[17] The white men "had crossed onto Indian land in violation of a recent treaty."[18] After Puckshinwa's death, Methoataske may have gone to live with her Creek relatives prior to moving west with the Kispoko in 1779. Methoataske left Tecumseh and his siblings under the care of their married older sister, Tecumapese. Wahskiegaboe, Tecumapese's husband, later became one of Tecumseh's supporters.[13][19]

Chiksika or Cheeseekau, Tecumseh's eldest brother and a leading warrior, essentially raised him. Chiksika took Tecumseh hunting and taught him to become a warrior; however, their younger brother, Lalawethika, who later changed his name to Tenskwatawa, stayed behind and showed little evidence of the powerful spiritual leader and close partnership he would form with Tecumseh as an adult.[20][21]

Early experiences[edit]

During the American Revolutionary War, the Shawnee were military allies of the British and repeatedly battled the Americans. Following his father's death, Tecumseh's family moved to Chief Blackfish's nearby village of Chillicothe. They remained there until the Kentucky militia destroyed it in retaliation for Blackfish's attack on Boonesborough, Kentucky.[22] Tecumseh's family fled to another nearby Kispoko village, but forces under the command of George Rogers Clark destroyed it in 1780. Next, the family moved to the village of Sanding Stone, which Clark and his men attacked in November 1782, and Tecumseh's family relocated to a Shawnee settlement near present-day Bellefontaine, Ohio.[23] Some historians believe that witnessing the sacking of his childhood homes by the Americans was a catalyst to his drive to becoming a warrior like his father and older brother, Chiksika (Cheeseekau),[24] and to be like "a fire spreading over the hill and valley, consuming the race of dark souls".[18]

Tecumseh may have witnessed his first battle, the Battle of Piqua, in 1780, while he was still a young boy under Chiksika's supervision, but Tecumseh did not engage in combat. Tribal chiefs later recalled that Tecumseh became so frightened during the battle that he ran away; it was allegedly the only instance in Tecumseh's life where he fled the battlefield.[18][24]

After the American Revolutionary War ended in 1783, fifteen-year-old Tecumseh joined a band of Shawnee who intended to stop white settlers from invading their lands by attacking settlers' flatboats as thet traveled down the Ohio River from Pennsylvania. "For a while," the Indians "were so effective that river traffic virtually ceased."[18] Tecumseh participated in several raids on Americans between 1786 and 1788, and in time, he assumed leadership of his own band of warriors.[25]

The Northwest Indian War brought continued violence to the American frontier. The Wabash Confederacy, a large tribal alliance that included all the major tribes of Ohio and the Illinois Country formed to repel the American settlers from the region. As the war between the Indian confederacy and the Americans expanded in the late 1780s and Tecumseh grew older, he began training to become a warrior and to fight alongside with his older brother Chiksika, an important war leader.[26]

In late 1789 or early 1790, Tecumseh traveled south with Chiksika to live among and fight alongside the Chickamauga faction of the Cherokee. During their trip south, Tecumseh fell from his horse during a hunting expedition and broke a bone in his thigh. The injury took several months to heal and caused him to walk with a slight limp for the remainder of his life. Accompanied by twelve Shawnee warriors, the brothers stayed at Running Water in Marion County, Tennessee, where Chiksika's wife and daughter lived. There Tecumseh met Dragging Canoe, a Chickamauga leader who was leading Indian resistance to American expansionism. Tecumseh remained with the Chickamauga for nearly two years. During this time he fathered a daughter with a Cherokee; however, the relationship was brief and the child remained with her mother.[27]

After a brief return to the Ohio Country in 1791, Tecumseh and his band of Shawnee warriors rejoined his brother in the Cumberland River area in Tennessee, where Chiksika was killed while leading a raid in September 1792. Tecumseh assumed leadership of the small Shawnee band and subsequent Chickamauga raiding parties before he returned to the Ohio Country at the end of 1792.[28] Afterwards, Tecumseh took part in several battles, including that of the Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794), in which the Americans defeated the Indians to end the Northwestern Indian Wars in the Americans' favor.[29][30] Despite the loss, Tecumseh refused to sign the Treaty of Greenville (1795), in which the Indians ceded large tracts of their lands in the Old Northwest Territory (about two-thirds of the present-day state of Ohio and portions of present-day Indiana) in exchange for goods valued at $20,000.[31][32]

Tecumseh took a wife, Mamate, and had a son, Paukeesaa, born about 1796. Their marriage did not last. Tecumseh's sister, Tecumapese, raised Paukeesaa from the age of seven or eight.[33]

Tenskwatawa and Prophetstown[edit]

Tecumseh's younger brother, Lalawethika ("He Makes A Loud Noise" or "Noise Maker"), who later took the new name of Tenskwatawa ("The Open Door" or "One with Open Mouth") and became known as "The Prophet" or "The Shawnee Prophet", was part of a set of triplet brothers born in early 1775. (One of the triplets died within the first year of his birth, but Lalawethika and his triplet brother Kumskaukau survived.[30]) Lalawethika's early years as a depressed and isolated young man were marked by numerous failures and alcoholism.[20][21] However, around 1805 Tenskwatawa began preaching and soon emerged as a powerful and influential religious leader of a spiritual revival. The Prophet's beliefs were based on the earlier teachings of the Lenape prophets, Scattamek and Neolin, who predicted a coming apocalypse that would destroy the European-American settlers.[34]

The Prophet attracted a large following among Indians who had suffered from epidemics and dispossession of their lands. He urged them to reject the American way of life and to return to their traditional ways. The Prophet wanted Indians to reject the white man's customs, which included firearms, consumption of alcohol, and European-style clothing. He also urged his followers to pay traders only half the value of their debts and to refrain from ceding any more lands to the U.S. government.[20][30]

Tecumseh eventually settled near Greenville, Ohio, in an Indian community that Tenskwatawa formed with his followers along the White River in western Ohio in 1805.[35] Tenskwatawa, who proved to be harsh, even brutal, in his treatment of those who opposed him and his teachings accused his detractors and anyone who associated with Americans of witchcraft.[36][37] His teachings also led to rising tensions between the settlers and his followers. Opposing Tenskwatawa was the Shawnee leader Black Hoof, who was working to maintain a peaceful relationship with the United States.[34]

The earliest record of Tecumseh's interaction with the Americans occurred in 1807, when U.S. Indian agent William Wells met with Blue Jacket and other Shawnee leaders in Greenville to determine their intentions after the recent murder of a settler. Tecumseh, who was among those who spoke with Wells and assured him that his band of Shawnee intended to remain at peace and wanted only to follow the will of the Great Spirit and his prophet. According to Wells's report, Tecumseh also told him that the Prophet intended to move with his followers deeper into the frontier, away from American settlements.[38] By 1808, as tensions between the Indians at Greenville and the encroaching settlers increased, Black Hoof demanded that Tenskwatawa and his followers leave the area. According to Tenskwatawa's later account, Tecumseh was already contemplating a pan-tribal confederacy to counter American expansion into Indian-held lands.[39]

In 1808 the Prophet and Tecumseh were leaders of the group that decided to move further west and establish a village near the confluence of the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers (near Battle Ground, north of present-day Lafayette, Indiana). Although the site was in Miami tribal territory and their chief, Little Turtle, warned the group not to settle there, the Shawnee ignored the warning and moved into the region; the Miami left them alone. The Americans called the Indian settlement Prophetstown, after the Shawnee spiritual leader. The village gained significance as a central point in the political and military alliance that was forming around Tecumseh, a natural and charismatic leader.[20]

As Tenskwatawa's religious teachings became more widely known, he attracted numerous followers to Prophetstown that included members of other tribes. The village soon expanded to form a large, multi-tribal community in the southwestern Great Lakes region that served as a major center of Indian culture, a temporary barrier to the encroaching settlers' westward movement, and a base to expel the whites and their culture from the territory. The community attracted thousands of Algonquin-speaking Indians and became an intertribal, religious stronghold within the Indiana Territory for 3,000 inhabitants.[20]

Tecumseh emerged as the primary leader and war chief of the confederation of warriors at Prophetstown. Recruits came from an estimated fourteen different tribal groups, although the majority were members of Shawnee, Delaware, and Potawatomi tribes.[20][40][41] The growing community at Prophetstown also caused increasing concerns among Americans in the area to fear that Tecumseh was forming an army of warriors to destroy their settlements.[42]

In 1811 Tenskwatawa precipitated the Battle of Tippecanoe when he was overcome by his power and defied Tecumseh's orders to evacuate if Harrison approached the village of Prophetstown. Tenskwatawa claimed to have had a vision and spoke to the tribes "in the voice of Moneto," their god, to attack as the white men could not hurt them, and that no one could die or would feel harm. The loss of this battle brought an end to the Prophet's influence among the Indian confederacy and caused many tribes to lose faith in Tecumseh's great plan of a strong Indian alliance.[43][44]

Tecumseh's War[edit]

Portraits of Pushmataha (left) and Tecumseh (right). "These white Americans ... give us fair exchange, their cloth, their guns, their tools, implements, and other things which the Choctaws need but do not make ... So in marked contrast with the experience of the Shawnee, it will be seen that the whites and Indians in this section are living on friendly and mutually beneficial terms." — Pushmataha, 1811[45] |

Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison,[47] the two principal adversaries in Tecumseh's War, had both been junior participants in the Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794) at the end of the Northwest Indian War. Although Tecumseh was not among the signers of the Treaty of Greenville (1795) that ceded much of present-day Ohio, long inhabited by the Shawnee and other American Indians, to the U.S. government, many of the Indian leaders in the region accepted the Greenville treaty's terms. For the next ten years pan-tribal resistance to American hegemony faded.

After the Treaty of Greenville was signed, most of the Shawnee in Ohio settled at the Shawnee village of Wapakoneta on the Auglaize River, where Black Hoof, a senior chief who had signed the treaty was their leader. Little Turtle, a Miami war chief, a participant in the Northwest Indian War, and a signer of the treaty at Greenville, lived in his village along the Eel River. Black Hoof and Little Turtle urged cultural adaptation and accommodation with the United States. The tribes of the region also participated in several additional treaties, including the Treaty of Vincennes (1803 and 1804) and the Treaty of Grouseland (1805), that ceded Indian-held land in southern Indiana to the Americans. The treaties granted the Indians annuity payments and other reimbursements in exchange for their lands.[48]

Rising tensions[edit]

In September 1809, William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, negotiated the Treaty of Fort Wayne in which a delegation of Indians in the Wabash River area ceded 2.5 to 3 million acres (12,000 km2) of land in what is present-day Indiana and Illinois to the U.S. government. The validity of the treaty negotiations were challenged with claims that the U.S. president, and thus the U.S. government, had not authorized them. The negotiations also involved what some historians have described as bribes, which included offering large subsidies to the tribes and their chiefs, and liberal distribution of liquor before the negotiations began.[49]

Tecumseh and his brother, Tenskwatawa, who adamantly wanted to retain their independence from the Americans, denounced the treaty, became openly hostile to those who had signed it, including other tribal leaders, and began recruiting members to their pan-Indian alliance.[50] Tecumseh emerged as a prominent war chief and leader among the Indians who opposed the treaty. Although the Shawnee had no claim on the land ceded to the U.S. government under the Treaty of Fort Wayne, he was angered because many of those who lived in Prophetstown were Piankeshaw, Kickapoo, and Wea, the primary inhabitants of the ceded lands. Tecumseh revived an idea advocated in previous years by the Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant that stated that Indian land was owned in common by all.[51]

Tecumseh was not ready to confront the United States directly. His primary adversaries were initially the Indian leaders who had signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne. Tecumseh, an impressive orator, began to travel widely, urging warriors to abandon the accommodationist chiefs and to join his resistance movement.[52] He insisted that the Fort Wayne treaty was illegal and asked Harrison to nullify it. Tecumseh also warned that the Americans should not attempt to settle on the ceded lands and claimed that "the only way to stop this evil [loss of land] is for the red man to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land, as it was first, and should be now, for it was never divided."[53]

Harrison's Confrontation[edit]

Tecumseh met with William Henry Harrison in 1810 and in 1811 to demand that the U.S. government rescind its land cession treaties with the Shawnee and other tribes. Harrison refused. In mid-August 1810, Tecumseh led 400 armed warriors from Prophetstown to confront Harrison at Grouseland, the territorial governor's home at Vincennes. The warriors' appearance startled the townspeople and the gathering quickly became hostile after Harrison rejected Tecumseh's demands. Harrison argued that individual tribes could have relations with the U.S. government and claimed that the tribes of the area did not welcome Tecumseh's interference.[54] Tecumseh's response to Harrison's remarks included his impassioned rebuttal:

Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children? How can we have confidence in the white people?[55]

Afterwards, some witnesses to the gathering claimed that Tecumseh had incited the warriors to kill Harrison, who responded by drawing his sword from its sheath at his side. The small garrison defending the town quickly moved to protect the territorial governor; the Potawatomi chief, Winnemac, stood and countered Tecumseh's arguments to the group, urging the warriors to leave peacefully. As the warriors departed, Tecumseh warned Harrison that unless the Treaty of Fort Wayne was rescinded, he would seek an alliance with the British.[56]

In July 1811, Tecumseh, accompanied by an estimated 300 warriors, met with Harrison at his home in Vincennes. Tecumseh told Harrison that the Shawnee and their Indiana allies wanted to remain at peace with the United States; however, their differences had to be resolved. The meeting proved to be unproductive. Harrison believed that the Indians were "simply looking forward to a quarrel."[57]

Tecumseh's pan-Indian campaign[edit]

Following the late July meeting with Harrison in 1811, Tecumseh traveled south, on a mission to recruit allies among the Five Civilized Tribes. The war speech he delivered to the Muscogee (Creek) at Tuckaubatchee, in October 1811, was so reported by John Francis Hamtramck Claiborne in 1860, its account being credited to General Samuel Dale, who was allegedly present at the meeting:[58]

In defiance of the white warriors of Ohio and Kentucky, I have traveled through their settlements, once our favorite hunting grounds. No war-whoop was sounded, but there is blood on our knives. The Pale-faces felt the blow, but knew not whence it came. Accursed be the race that has seized on our country and made women of our warriors. Our fathers, from their tombs, reproach us as slaves and cowards. I hear them now in the wailing winds. The Muscogee was once a mighty people. The Georgians trembled at your war-whoop, and the maidens of my tribe, on the distant lakes, sung the prowess of your warriors and sighed for their embraces. Now your very blood is white; your tomahawks have no edge; your bows and arrows were buried with your fathers. Oh! Muscogees, brethren of my mother, brush from your eyelids the sleep of slavery; once more strike for vengeance; once more for your country. The spirits of the mighty dead complain. Their tears drop from the weeping skies. Let the white race perish. They seize your land; they corrupt your women; they trample on the ashes of your dead! Back, whence they came, upon a trail of blood, they must be driven. Back! back, ay, into the great water whose accursed waves brought them to our shores! Burn their dwellings! Destroy their stock! Slay their wives and children! The Red Man owns the country, and the Pale-faces must never enjoy it. War now! War forever! War upon the living! War upon the dead! Dig their very corpses from the grave. Our country must give no rest to a white man's bones. This is the will of the Great Spirit, revealed to my brother, his familiar, the Prophet of the Lakes. He sends me to you. All the tribes of the north are dancing the war-dance. Two mighty warriors across the seas will send us arms. Tecumseh will soon return to his country. My prophets shall tarry with you. They will stand between you and the bullets of your enemies. When the white men approach you the yawning earth shall swallow them up. Soon shall you see my arm of fire stretched athwart the sky. I will stamp my foot at Tippecanoe, and the very earth shall shake.[59][60]

The above account has since remained very popular, being continually mentioned and quoted in books, reviews and websites. Its trustworthiness however was already questioned in 1895 by historians Henry Sale Halbert and Timothy Horton Ball, according to whom "there is no reasonable evidence that it contains the substance of the statements of Tecumseh", and it shows a "murderous, vengeful, barbarous Tecumseh of imagination rather than of fact".[61] Some ninety years later the whole question was thoroughly examined again by British historian John Sugden, who came to even sharper conclusions: "Claiborne's description of Tecumseh at Tuckabatchie ... is fraudulent"[62] and "students are ... warned against using [his] influential but bogus accounts".[63]

Here is also, however, the text of quite a different-toned speech Tecumseh allegedly delivered to a band of Osages on his way back home in 1811. It was reported by John Dunn Hunter, an Anglo-American whose parents had been killed by the Kickapoos, and who had been later raised among the Osages:[64]

Brothers, we all belong to one family; we are all children of the Great Spirit; we walk in the same path; slake our thirst at the same spring; and now affairs of the greatest concern lead us to smoke the pipe around the same council fire! Brothers, we are friends; we must assist each other to bear our burdens. The blood of many of our fathers and brothers has run like water on the ground, to satisfy the avarice of the white men. We, ourselves, are threatened with a great evil; nothing will pacify them but the destruction of all the red men. Brothers, when the white men first set foot on our grounds, they were hungry; they had no place on which to spread their blankets, or to kindle their fires. They were feeble; they could do nothing for themselves. Our fathers commiserated their distress, and shared freely with them whatever the Great Spirit had given his red children. They gave them food when hungry, medicine when sick, spread skins for them to sleep on, and gave them grounds, that they might hunt and raise corn. Brothers, the white people are like poisonous serpents: when chilled, they are feeble and harmless; but invigorate them with warmth, and they sting their benefactors to death. The white people came among us feeble; and now that we have made them strong, they wish to kill us, or drive us back, as they would wolves and panthers. Brothers, the white men are not friends to the Indians: at first, they only asked for land sufficient for a wigwam; now, nothing will satisfy them but the whole of our hunting grounds, from the rising to the setting sun. Brothers, the white men want more than our hunting grounds; they wish to kill our old men, women, and little ones. Brothers, many winters ago there was no land; the sun did not rise and set; all was darkness. The Great Spirit made all things. He gave the white people a home beyond the great waters. He supplied these grounds with game, and gave them to his red children; and he gave them strength and courage to defend them. Brothers, my people wish for peace; the red men all wish for peace; but where the white people are, there is no peace for them, except it be on the bosom of our mother. Brothers, the white men despise and cheat the Indians; they abuse and insult them; they do not think the red men sufficiently good to live. The red men have borne many and great injuries; they ought to suffer them no longer. My people will not; they are determined on vengeance; they have taken up the tomahawk; they will make it fat with blood; they will drink the blood of the white people. Brothers, my people are brave and numerous; but the white people are too strong for them alone. I wish you to take up the tomahawk with them. If we all unite, we will cause the rivers to stain the great waters with their blood. Brothers, if you do not unite with us, they will first destroy us, and then you will fall an easy prey to them. They have destroyed many nations of red men, because they were not united, because they were not friends to each other. Brothers, the white people send runners amongst us; they wish to make us enemies, that they may sweep over and desolate our hunting grounds, like devastating winds, or rushing waters. Brothers, our Great Father[65] over the great waters is angry with the white people, our enemies. He will send his brave warriors against them; he will send us rifles, and whatever else we want—he is our friend, and we are his children. Brothers, who are the white people that we should fear them? They cannot run fast, and are good marks to shoot at: they are only men; our fathers have killed many of them: we are not squaws, and we will stain the earth red with their blood. Brothers, the Great Spirit is angry with our enemies; he speaks in thunder, and the earth swallows up villages, and drinks up the Mississippi. The great waters will cover their lowlands; their corn cannot grow; and the Great Spirit will sweep those who escape to the hills from the earth with his terrible breath. Brothers, we must be united; we must smoke the same pipe; we must fight each other’s battles; and, more than all, we must love the Great Spirit: he is for us; he will destroy our enemies, and make all his red children happy.[66]

Despite Tecumseh's efforts, most of the southern nations rejected his appeals, especially the Choctaw chief, Pushmataha, who opposed Tecumseh's pan-Indian alliance and insisted upon adhering to the terms of the peace treaties that had been signed with the U.S. government.[67] However, a faction among the Creeks, who came to be known as the Red Sticks, responded to Tecumseh's call to arms that lead to the Creek War.[56] Tecumseh, whose name meant "shooting star", also told the Creeks that the arrival of a comet signaled his coming and that the confederacy and its allies took it as an omen of good luck. McKenney reported that Tecumseh claimed he would prove that the Great Spirit had sent him to the Creeks by giving the tribes a sign.

Battle of Tippecanoe[edit]

When Harrison heard from intelligence that Tecumseh was away, he reported to the U.S. Department of War that Tecumseh was putting "a finishing stroke upon his work. I hope, however, before his return that that part of the work which he considered complete will be demolished and even its foundation rooted up."[68] Harrison decided to strike first, while Tecumseh was absent, and force the Indians from Prophetstown, which he thought posed a threat to the region, and destroy the village.[42][69] Harrison marched from Vincennes on September 26, 1811, with more than 1,200 men toward Prophetstown, where he intended to intimidate the Prophet's followers and weaken the spiritual leader's influence.[70]

In the meantime, Tenskwatawa thought that a skirmish with Harrison's men would persuade more Indians to join the alliance. Tenskwatawa decided to make the first strike against Harrison's army instead of following through on an agreement that he had previously made with Tecumseh to evacuate Prophetstown if the American military approached the village. Prior to the battle, the Prophet claimed that they would not be harmed if they attacked the white men and the warriors would not die.[42][71]

On November 6, 1811, when Harrison and about 1,000 of his men approached Prophetstown, the Prophet sent a messenger to request a meeting with Harrison to negotiate. Harrison agreed to meet with him the following day and encamped with his army on a nearby hill about two miles from Prophetstown. In the pre-dawn hours on November 7, an estimated 600 to 700 warriors launched a surprise attack on Harrison's camp to initiate the Battle of Tippecanoe. Harrison's men held their ground in the two-hour engagement, but the Prophet's warriors withdrew from the field and abandoned Prophetstown after the battle. The Americans burned the village to the ground the following day and returned to Vincennes.[72][73]

An American Indian named Shabonee later explained in his firsthand account of the events that Harrison initially intended to negotiate, but the Indians were prepared to fight. The Shawnee reported that the young warriors had said, "We are ten to their one. If they stay upon one side, we will let them alone. If they cross the Wabash we will take their scalps or drive them into the river."[74] Shabonee also asserted that Tenskwatawa attacked at the urging of Canadians and "the battle of Tippecanoe was the work of white men who came from Canada and urged us to make war."[75]

The battle did not end the Indians' resistance to the Americans. Despite the loss at Prophetstown, Tecumseh continued his role as the military leader of the pan-Indian alliance and began to rebuild its membership. However, many tribes lost faith and his great plan to establish a stronger Indian alliance was never fulfilled.[43] The battle was also a severe blow for Tenskwatawa's prestige. He lost his influence among the Indians, as well as the confidence of his brother. The Prophet became an outcast and eventually moved to Canada, where he served as one of Tecumseh's subordinates during the War of 1812.[76][77]

When the Americans went to war with the British in 1812, Tecumseh's War became a part of that struggle.[72] On December 16, 1811, the New Madrid earthquake shook the South and the Midwest. Although the interpretation of this event varied from tribe to tribe, one consensus was universally accepted: the powerful earthquake had to have meant something. For many tribes in the pan-Indian alliance, it meant that Tecumseh and the Prophet must be supported.[78]

War of 1812[edit]

Siege of Detroit[edit]

Tecumseh rallied his confederacy and allied his forces with the British army invading the Northwest Territory from Upper Canada. He joined British Major-General Sir Isaac Brock in the Siege of Detroit, helping to force the city's surrender in August 1812. At one point in the battle, as Brock advanced to a point just out of range of Detroit's guns, Tecumseh had his approximately 400 warriors parade out from a nearby wood and circle back around to repeat the maneuver, making it appear that there were many more men under his command than was actually the case. Brigadier General William Hull, the fort commander, surrendered in fear of a massacre. The victory was of a great strategic value to the British allies.[79]

Tecumseh was made a brigadier general in the British army as the commander in chief of its Indian allies. In an effort to honor Tecumseh for his help during the siege, Major-General Henry Procter, the next British commander in the region, awarded him a sash, but Tecumseh returned it "with respectful contempt."[80]

The victory at Detroit was reversed a little over a year later, when Commodore Perry's victory on Lake Erie in the summer of 1813 cut the British supply lines. Along with William Henry Harrison's successful defense of Fort Meigs, which created a staging area for the recapture of Fort Detroit, the British found themselves in an indefensible position and had to withdraw from the city. They burned all public buildings in Detroit and retreated into Upper Canada along the Thames Valley. Tecumseh sought continued British support in order to defend tribal lands against the Americans. However, a much reinforced Harrison led an invasion of Canada.

Siege of Fort Meigs[edit]

The siege began on May 5, 1813, when a small British force of less than 1,000 men under the command of Major-General Procter, the British commander on the Detroit frontier, and an estimated 1,250 Indian warriors led by Tecumseh and the Wyandot leader, Roundhead, attempted to capture Fort Meigs in northwestern Ohio.[81] The British hoped that the effort would delay an American offensive attack against Detroit, which the British had captured in 1812. The American force of 1,100 men suffered heavy casualties, but the British and their Indian allies failed to capture Fort Meigs. On May 7, terms were arranged providing for exchange or parole of British and American prisoners.[82]

After the initial battle, some of the Indian warriors succeeded in killing several American prisoners before Tecumseh, Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Elliott, and Captain Thomas McKee of the Indian Department persuaded them to stop.[83] Tecumseh reportedly asked Procter why he had not stopped the massacre. Procter, who complained that the Indians could not be made to obey, replied, "Begone! You are unfit to command. Go and put on petticoats."[84] According to another account of the incident, Tecumseh supposedly rebuked Procter with the remark, "I conquer to save; you to kill."[85] Eyewitnesses estimated between twelve and fourteen Americans were killed in the massacre.[86] Tecumseh's actions during the event are thought to be a major reason why he later became a hero also in the United States and is considered a "noble savage."[87]

Battle of the Thames[edit]

Major-General Procter did not have the same working relationship with Tecumseh as his predecessor Isaac Brock. Tecumseh and Proctor disagreed over tactics. While Procter favored withdrawal into Canada to avoid further battles, leaving the Americans to suffer through the hardships of winter, Tecumseh was more eager to launch an immediate and decisive action to defeat the Americans and allow his warriors to retake their homelands in the northwest.[88] Meanwhile, Harrison pursued the retreating British and allied tribes. When Procter's forces failed to appear at Chatham in Upper Canada (although he had promised Tecumseh that he would make a stand there against the Americans), Tecumseh reluctantly moved his men to meet up with Procter's troops near Moraviantown. Tecumseh informed Procter that he would withdraw no farther and announced that if the British wanted his continued help, they needed to wait for the arrival of Harrison's army and fight. At the conclusion of an impassioned speech Tecumseh declared:

Our lives are in the hands of the Great Spirit. We are determined to defend our lands, and if it be his will, we wish to leave our bones upon them.[89]

On October 5, 1813, the Americans attacked and won a victory over the British and Native Americans at the Battle of the Thames, near Moraviantown. Tecumseh was killed.[90][91] After the battle, most of the Indian confederacy surrendered to Harrison at Detroit and returned to their homes.[92][93]

Death[edit]

The circumstances surrounding Tecumseh’s death are unclear due to several conflicting accounts. Some sources claim that Colonel Richard Johnson killed Tecumseh during a cavalry charge.[94] However, the Wyandott historian, Peter D. Clarke, offered a different explanation after talking with Indians who had fought in the battle: "[A] Potawatamie brave, who, on perceiving an American officer (supposed to be Colonel Johnson) on horse ... turned to tomahawk his pursuer, but was shot down by him with his pistol .... The fallen Potawatamie brave was probably taken for Tecumseh by some of Harrison's infantry, and mutilated soon after the battle."[95]

John Sugden, who provided an in-depth examination of Tecumseh's death in his book, Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985), suggested that crediting Johnson for taking Tecumseh's life would have, and did, greatly enhanced Johnson's political career. In 1836, when Johnson was elected U.S. Vice President, and again in 1840, his campaign supporters used the slogan, "Rumpsey Dumpsey, Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh."[94][96] However, after an exhaustive study, Sugden could not conclude that Johnson killed Tecumseh.[97]

In another account, "A half-Indian and half-white, named William Caldwell .... overtook and passed Tecumseh, who was walking along slowly, using his rifle for a staff—when asked by Caldwell if he was wounded, he replied in English, 'I am shot'—Caldwell noticed where a rifle bullet had penetrated his breast, through his buckskin hunting coat. His body was found by his friends, where he had laid [sic] down to die, untouched, within the vicinity of the battle ground ...."[98] Several of Harrison's men also claimed to have killed Tecumseh; however, none of them were present when Tecumseh was mortally wounded.[98]

Other sources have credited William Whitley as the person responsible for Tecumseh's death, but Sugden argued that Whitely had been killed in battle prior to Tecumseh's death.[99] In his 1929 autobiography, James A. Drain Sr., Whitley's grandson, continued to claim that his grandfather single-handedly shot and killed Tecumseh. As Drain explained it, Whitley was mortally wounded, but he saw Tecumseh spring towards him, "intent upon taking for himself a scalp," and drew his gun "to center his sights upon the red man's breast. And as he fired, he fell and the Indian as well, each gone where good fighting men go."[100]

Edwin Seaborn, who recorded an oral history from Saugeen First Nation in the 1930s, provides another account of Tecumseh's death. Pe-wak-a-nep, who was seventy years old in 1938, describes his grandfather’s eyewitness account of Tecumseh’s last battle. Pe-wak-a-nep explained that Tecumseh was fighting on a bridge when his lance snapped. Tecumseh "fell after ‘a long knife’ was run through his shoulder from behind."[101]

Sugden concluded that Tecumseh was killed during the fierce fighting in the opening engagement between the Indians and Johnson's mounted regiment. Shortly after his death, the Indians retreated from the battle and headed toward Lake Ontario. The details of how he died remain unclear. Tecumseh's body was identified by British prisoners after the battle and examined by some Americans who knew him and could confirm that its injuries were consistent with earlier wounds that Tecumseh has suffered to his legs (a broken thigh and a bullet wound). The body had a fatal wound to the left breast and also showed damage to the head by a blow, possibly inflicted after his death.[102]

According to Sugden, Tecumseh's body had been defiled, although later accounts were likely exaggerated. Sugden also discounted some conflicting Indian accounts that indicated his body had been removed from the battlefield before it could be mutilated. From his analysis of the evidence, Sugden firmly claimed that Tecumseh's remains, mutilated beyond recognition, were left on the battlefield.[103] Sugden's Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985) also recounted varied accounts of Tecumseh's burial and the still unknown location of his gravesite.[104]

Legacy[edit]

Tecumseh was an energetic warrior, a respected war chief, and a strong and eloquent orator, whose lifelong goal was to repel the Americans from Indian lands. He and his brother, Tenskwatawa, founded Prophetstown, a large, multi-tribal community that attracted thousands and became a major center of Indian culture, a temporary barrier to encroaching settlers, and a central point for the political and military alliance that was forming around Tecumseh. With a base of supporters in Prophetstown, Tecumseh became the principal organizer and driving force of a multi-tribal confederacy of American Indians. Tecumseh's message promoted tribal unity; he adamantly insisted that tribal lands belong collectively to all Indians.[43][105]

After the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, Tecumseh resumed his role as the military leader of the pan-Indian confederation, but the battle ended his plan to form a larger, pan-Indian alliance. Tecumseh and the Indian resistance movement allied with the British against the Americans during the War of 1812, but his death at the Battle of the Thames in 1813 and the end of War of 1812 led to the collapse of the alliance. Over the next several years the Indians ceded their remaining land east of the Mississippi River to the U.S. government. As most of the Indians removed to reservation land in the western United States, white settlers claimed the former Indian lands in the Old Northwest Territory for themselves.[43][105]

Tecumseh is considered "one of the most sophisticated and celebrated Indian leaders in all history."[106] However, his weaknesses as an ambitious, impulsive, and arrogant leader willing to make significant sacrifices, including risking the lives of his followers, impacted the Indian resistance movement. Despite his relentless efforts, the pan-Indian alliance was not successful in achieving its goal of retaining control of Indian lands in the Old Northwest Territory.[107]

Consequences for Native Americans[edit]

Tecumseh's death was a decisive blow to the American Indians. It had larger implications during negotiations for the Treaty of Ghent (1814). During the treaty process, the British called for the U.S. government to return lands in Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan to the Indians. For decades the British strategy had been to create a buffer state to block American expansion, but the Americans refused to consider the British proposal and it was dropped.[108] Although Article IX of the treaty included provisions to restore to native inhabitants "all possessions, rights and privileges which they may have enjoyed, or been entitled to in 1811", the provisions were unenforceable.[109]

Tecumseh's dream of a pan-Indian confederation would not be realized until 1944, with the founding of the National Congress of American Indians.[citation needed]

Notable quotes[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tecumseh |

Noted by Indian, American, and English colleagues, allies, and enemies as an inspiring orator, Tecumseh left these words to live by:

Live your life so that the fear of death can never enter your heart ... Love your life, perfect your life, beautify all things in your life. Seek to make your life long and in the service of your people...

Always give a word or a sign of salute when meeting or passing a friend, even a stranger, when in a lonely place. Show respect to all people and grovel to none. When you arise in the morning give thanks for the food and for the joy of living. If you see no reason for giving thanks, the fault lies only in yourself...

When it comes your time to die, be not like those whose lives are filled with the fear of death, so that when time comes they weep and pray for a little more time to live their lives over again in a different way. Sing your death song and die like a hero going home.[110]

He rallied many tribes to his alliance by his attacks on white people:

Brothers – the white people are like poisonous serpents: when chilled they are feeble and harmless, but invigorate them with warmth and they sting their benefactors to death.[111]

Honors and memorials[edit]

Canada[edit]

Tecumseh is honored in Canada as a hero and military commander who played a major role in Canada's successful repulsion of an American invasion in the War of 1812, which, among other things, eventually led to Canada's nationhood in 1867 with the British North America Act. Among the tributes, Tecumseh is ranked 37th in The Greatest Canadian list. The Canadian naval reserve unit HMCS Tecumseh is based in Calgary, Alberta. The Royal Canadian Mint released a two dollar coin on June 18, 2012 and will release four quarters, celebrating the Bicentennial of the War of 1812. The second quarter in the series, was released in November 2012 and features Tecumseh.[112]

The Ontario Heritage Foundation & Kent Military Reenactment Society erected a plaque in Tecumseh Park, 50 William Street North, Chatham, Ontario, reading: "On this site, Tecumseh, a Shawnee Chief, who was an ally of the British during the war of 1812, fought against American forces on October 4, 1813. Tecumseh was born in 1768 and became an important organizer of native resistance to the spread of white settlement in North America. The day after the fighting here, he was killed in the Battle of Thames near Moraviantown. Tecumseh park was named to commemorate strong will and determination."[113]

He is also honored by a massive portrait which hangs in the Royal Canadian Military Institute. The unveiling of the work, commissioned under the patronage of Kathryn Langley Hope and Trisha Langley, took place at the Toronto-based RCMI on October 29, 2008.[114]

A replica of the War of 1812 warship HMS Tecumseh was built in 1994 and displayed in Penetanguishene, Ontario, near the raised wreck of the original HMS Tecumseh. The original HMS Tecumseh was built in 1815 to be used in defense against the Americans. First on Lake Erie, she moved to Lake Huron in 1817. She sank in Penetanguishene harbor in 1828, and was raised in 1953.[115]

U.S. Military[edit]

The United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, has Tecumseh Court, which is located outside Bancroft Hall's front entrance, and features a bust of Tecumseh. The bust is often decorated to celebrate special days. The bust was originally meant to represent Tamanend, an Indian chief from the 17th century who was known as a lover of peace and friendship, but the Academy's midshipmen preferred the warrior Tecumseh, and have referred to the statue by his name.[116]

Four ships of the United States Navy have been named USS Tecumseh.

- The first USS Tecumseh (1863), was a Canonicus-class monitor, commissioned on 19 April 1864. It was lost with almost all hands on 5 August, at the Battle of Mobile Bay.

- The second USS Tecumseh (YT-24), was a tugboat, originally named Edward Luckenbach, purchased by the Navy in 1898 and renamed. She served off and on until she was struck from the Navy list ca. 1945.

- The third USS Tecumseh (YT-273), was a Pessacus-class tugboat, commissioned in 1943 and struck from service in 1975.

- The fourth USS Tecumseh (SSBN-628), was a James Madison-class ballistic missile submarine, commissioned in 1964 and struck in 1993.

Persons' names[edit]

Union Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman, was given the middle name of Tecumseh because "my father...had caught a fancy for the great chief of the Shawnees."[117] Another Civil War general, Napoleon Jackson Tecumseh Dana, also bore the name of the Shawnee leader. (Evolutionary biologist and cognitive scientist W. Tecumseh Fitch was named after Sherman, and thus only indirectly for the chief.)

Town names[edit]

A number of towns have been named in honor of Tecumseh, including those in the states of Kansas, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and the province of Ontario, as well as the town and township of New Tecumseth, Ontario, and Mount Tecumseh in New Hampshire.

School names[edit]

Schools named in honor of Tecumseh include, in the United States: Tecumseh Junior – Senior High in Hart Township, Warrick County, just outside Lynnville, Indiana. Lafayette Tecumseh Junior High in Lafayette, Indiana. Tecumseh-Harrison Elementary[118] in Vincennes, Indiana. Tecumseh Acres Elementary, Tecumseh Middle and Tecumseh High in Tecumseh, Michigan.[119] Tecumseh Elementary in Farmingville, New York. Tecumseh Elementary in Jamesville, New York. Tecumseh Middle and Tecumseh High in Bethel Township, Clark County near New Carlisle, Ohio and their district, the Tecumseh Local School District. Tecumseh Elementary in Xenia Township, Greene County near Xenia, Ohio. Tecumseh Middle[120] and Tecumseh High in Tecumseh, Oklahoma. And in Canada: Tecumseh Elementary[121] in Vancouver. Tecumseh Public[122] in Burlington, Ontario. Tecumseh Public School in Chatham, Ontario.[citation needed] Tecumseh Public School in London, Ontario.[citation needed] Tecumseh Senior Public[123] in Scarborough, Ontario.

Depictions[edit]

Benson Lossing's engraved portrait of Tecumseh, in his 1868 The Pictorial Fieldbook of the War of 1812 (p. 283),[124][125] was based on a sketch done from life in 1808. Lossing altered the original by putting Tecumseh in a British uniform, under the mistaken (but widespread) belief that Tecumseh had been a British general.[126] This depiction is unusual in that it includes a nose ring, popular among the Shawnee at the time, but typically omitted in idealized depictions.[127] On the other hand, the artist quotes Captain J. B. Glegg as follows: "Three small silver crosses or coronets were suspended from the lower cartilage of his aquiline nose[...]".[125][128] (Tecumseh's brother "The Prophet" is depicted with a nose ring in Lossing's book[129]—as well as by George Catlin.) Apart from Tecumseh's "gala dress" (at a celebration of the Surrender of Detroit) Lossing referred to, also his face may not be rendered faithfully—no fully authenticated portrait of the Shawnee leader exists.[126] In general, many known portraits and sculptures have been made decades after Tecumseh's death, by artists unfamiliar with Tecumseh's actual appearance.

Numerous depictions show how Colonel Richard Johnson, leading a cavalry attack of the Battle of the Thames, shot Tecumseh—see above for doubts (it has been reported that an Indian raised his tomahawk against Johnson and was shot by the latter, while some reports deny that this Indian was Tecumseh). These depictions range from a book illustration to a section of the frieze of the rotunda of the United States Capitol.

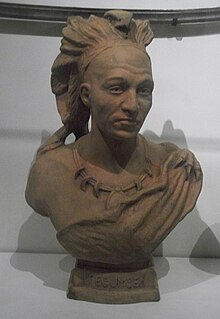

Sculptures[edit]

In Canada, the Royal Ontario Museum exhibits a bust of Tecumseh created by Hamilton MacCarthy in 1896.

German sculptor Ferdinand Pettrich (1798–1872) studied under the neo-classicist Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen in Rome and moved to the United States in 1835. He was especially impressed by the Indians. He modelled The Dying Tecumseh ca. 1837–1846; it was finished 1856 in marble and copper alloy. The sculpture was put on display in the U.S. Capitol, where a stereoscopic photograph was taken of it in the later 1860s; in 1916 it was transferred to the Smithsonian American Art Museum.[130]

In recent years, Peter Wolf Toth has created the Trail of the Whispering Giants, a series of sculptures honoring Native Americans. He donated one work devoted to Tecumseh to the City of Vincennes, which was Indiana's territorial capital in the years around 1810, where Tecumseh confronted governor William Henry Harrison, and in the area of which Tecumseh's war then happened and the War of 1812 started.[citation needed] In Lafayette, Indiana, Tecumseh appears along with the Marquis de Lafayette and Harrison in a pediment on the Tippecanoe County Courthouse (1882).[131]

Just west of Portsmouth, Ohio, there is a wood carving of the aged Tecumseh in Shawnee State Park's Shawnee Lodge and Conference Center.[citation needed]

In popular culture[edit]

Art and other media[edit]

- A twelve-part comic book version of the Orson Scott Card novel, Red Prophet. The cover of one of the issues of the comic book series was a copy of a painting featuring Tecumseh by John Buxton; the painting had been commissioned by the Heritage Center of Clark County, Ohio.[132]

- The outdoor drama Tecumseh![133] is performed near Chillicothe, Ohio, and was written by novelist/historian, Allan W. Eckert.[134]

- Tecumseh was a featured character in The Battle of Tippecanoe Outdoor Drama held in Battle Ground, Indiana, during the summers of 1989 and 1990.[135]

Film[edit]

- Tecumseh (1972) is an East German film, where Tecumseh is the main character. Tecumseh is played by Serbian actor Gojko Mitić.[136]

- Tecumseh: The Last Warrior (1995) is a movie about Tecumseh's life. Tecumseh is played by Jesse Borrego, who claims to have Native American ancestry.

- Tecumseh (played by Canadian actor, Lorne Cardinal) is featured in the 2000 documentary Canada: A People's History.

- Actor Michael Greyeyes portrayed Tecumseh in the 2009 documentary We Shall Remain.

- The poem "Live Your Life", allegedly composed by Tecumseh (but also ascribed to some of the Wabasha chiefs, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Wovoka)[137] was featured in the closing moments of the 2012 film Act of Valor.

Literature[edit]

- Ann Rinaldi's 1997 novel, The Second Bend in the River, depicts a fictionalized version of a romance between Tecumseh and Rebecca Galloway.[138]

- Orson Scott Card's novel, Red Prophet, featured Tecumseh (named Ta-Kumsaw).

- Mimi Malenšek's 1959 Slovene historical novel, Tecumseh: Indijanska kronika (Ljubljana, 303 pp.).

- James Alexander Thom's historical novel, Panther in the Sky, is a novelized biography of Tecumseh.

- Fritz Steuben Tecumseh-Reihe, Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung, Stuttgart 1930-1939.

- Allan W. Eckert's "Winning of America" series, volumes The Frontiersman, Wilderness Empire, The Conquerors, The Wilderness War, Gateway to Empire, Twilight of Empire and A Sorrow in Our Heart: The Life of Tecumseh, which depicts a major turning point in the American history - the settling of the Ohio River Valley.

- In Blood of Tyrants, the eight novel of Naomi Novik's Temeraire series, Tecumseh is revealed to be the President of the United States in 1813, having defeated Alexander Hamilton, suggesting that Indians are much more accepted in U.S. society in that alternative history.

- Longin Jan Okoń's Polish adventure novels Tecumseh (Lublin 1976), Czerwonoskóry generał (Lublin 1978) and Śladami Tecumseha (Lublin 1980).

Television[edit]

- A life-size statue of Tecumseh is featured in the sitcom Cheers.[139]

- Insurance company executive Randall tries to quote Tecumseh in the Mad Men season six episode, "The Flood".[140] In greeting Roger Sterling and the SCDP creative team hello and goodbye, Randall raises his hand in a stereotyped Native American gesture associated with "How"; this gesture is also a military greeting.[141]

See also[edit]

- Junaluska

- Shawnee people

- Curse of Tippecanoe also called Tecumseh's Curse

- Tenskwatawa

- Osceola

- Tecumseh's War

- William Henry Harrison

- War of 1812

- Battle of Tippecanoe

- Siege of Detroit

- Siege of Fort Meigs

- Battle of the Thames

Notes[edit]

- ^ J. Laxar (2012). Tecumseh & Brock: The War of 1812. House of Anansi Press. pp. 301–302. ISBN 9780887842610. According to Laxar, there are several competing claims regarding Tecumseh's final resting place. The bones found on Walpole Island do not contain a thigh bone, which is critical because Tecumseh broke his thigh while riding a horse when he was younger. Other competing claims for his resting place include the east end of London, Ontario, or alternatively, that he is buried near the site of his death.

- ^ Robert S. Allen (2009). "Tecumseh". The Canadian Encyclopedia-Biography-Native Political Leaders. Historica-Dominion. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ^ J. M. Bumsted (2009). The peoples of Canada: a pre-Confederation history. Oxford U.P. p. 244. ISBN 9780195431018.

- ^ The exact date of Tecumseh's birth is not known; however, John Sugden, a Tecumseh biographer, suggests it was March 1768, based on accounts from Stephen Ruddell, who first met Tecumseh when he was twelve and estimated that Tecumseh was about six months older than himself. See John Sugden (1998). Tecumseh: A Life. New York: Henry Holt and company. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-8050-4138-9.

- ^ "Birthplace of Tecumseh Marker". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Chalahgawtha was the name of one of the five bands of the Shawnee.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 20-23.

- ^ a b "The Family of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa". Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Sugden explained that Anthony Shane, "a mixed-blood who spent most of his life in Shawnee towns," and his wife Lameteshe, "one of Tecumseh's kindred," claimed that Puckshinwau's father was British and his mother was Shawnee. See Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 15.

- ^ Although the claim has not been endorsed by major later historians, according to one white family's tradition that Hazen Hayes Pleasant reported in his book on the history of Crawford County, Indiana, Tecumseh's father was reputed to have been a white man who was born in Crawford County, Indiana, and raised since childhood among the Shawnee. According to Pleasant: "The Wisemans claim that in the early history of the West a certain Wiseman boy was captured by the Indians who adopted him into the tribe of Shawnees. When he became a man, he married an Indian girl. To them was born an Indian boy who became the famous Tecumseh." See: Hazen Hayes Pleasant (1926). A History of Crawford County, Indiana. Greenfield, Indiana: William Mitchell. p. 16.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 13–16.

- ^ a b R. David Edmunds (1985). The Shawnee Prophet. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-8032-1850-8.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 13.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 16.

- ^ Benjamin Drake (1841). Life of Tecumseh, and His Brother the Prophet: With a Historical Sketch of the Shawanoe Indians. E. Morgan and Company. pp. 28–33.

- ^ a b c d "Famous Native Americans: Tecumseh Part 1". Retrieved May 8, 2010. (Reproduced from David Wallechinsky and Irving Wallace (1975–1981). The People's Almanac.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f James H. Madison (2014). Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press and the Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-253-01308-8.

- ^ a b Andrew R. L. Cayton (1996). Frontier Indiana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 205–9. ISBN 0253330483.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 33.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Drake, p. 68.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 47–52.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 37–39.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 54, 60–61, 66.

- ^ Allan W. Eckert (1983). Gateway To Empire. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 132–33; 139–41. ISBN 0316208612.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 76–78.

- ^ a b c James H. Madison and Lee Ann Sandweiss (2014). Hoosiers and the American Story. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-87195-363-6.

- ^ "Treaty of Greeneville (1795)". Ohio History Central. Ohio History Connection. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Glenn Tucker (August 19, 2014). "Tecumseh". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 98–99.

- ^ a b Robert M. Owens (2007). Mr. Jefferson's Hammer: William Henry Harrison and the Origins of American Indian Policy. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-0-8061-3842-8.

- ^ Edmunds, The Shawnee Prophet, p. 34.

- ^ Cayton, pp. 207–8.

- ^ Edmunds, The Shawnee Prophet, p. 39.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), pp. 4–7.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 9.

- ^ Owens, p. 210.

- ^ "Shawnee" in Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1996.

- ^ a b c Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

- ^ a b c d Gugin and St. Clair, eds., Indiana's 200, p. 347.

- ^ Eckert, pp. 387–90.

- ^ William R. Carmack (1979). Indian Oratory: A Collection of Famous Speeches by Noted Indian Chieftains. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 73.

- ^ Frederick Turner III (1978) [1973]. "Poetry and Oratory". The Portable North American Indian Reader. Penguin Book. pp. 246–47. ISBN 0-14-015077-3.

- ^ In 1801 William Henry Harrison became the first governor of the Indiana Territory and was elected president of the United States in 1840; he died in office on April 4, 1841. See Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press and the Indiana Historical Bureau. pp. 18, 25. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.

- ^ Cayton, pp. 210–12.

- ^ "Treaty with the Delawares, Etc., 1809". Indiana Historical Bureau. Archived from the original on July 21, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- ^ Cayton, pp. 216–17.

- ^ Owens, p. 203

- ^ Owens, p. 209.

- ^ Chapter 5, "Three-D Deeds: The Rise of Air Rights in New York," in Theodore Steinberg (1996). Slide Mountain, or, The Folly of Owning Nature. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 39621653.

- ^ A. J. Langguth (2006). Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 165. ISBN 0-7432-2618-6.

- ^ Frederick Turner III (1973). "Poetry and Oratory". The Portable North American Indian Reader. Penguin Books. pp. 245–46. ISBN 0-14-015077-3.

- ^ a b Langguth, p. 167.

- ^ Cayton, pp. 220–21.

- ^ (1860). Life and times of Gen. Sam. Dale, the Mississippi partisan. New York;, Harper & Brothers, pp. 59–61 (accessibile for free online at books.google)

- ^ Bunn, Mike; Clay Willams (2008). "Original Documents, Excerpt from Tecumseh's Speech at Tuckaubatchee, 1811". Battle for the Southern Frontier. The History Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-59629-371-7.

- ^ Battlefield Biker (2006–2008). "Shawnee Chief Tecumseh Delivers War Speech to Creek Indians at Tuckabatchee, Alabama in October 1811". Battlefield Biker. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ Halbert, H.S.; Ball, T.H. (1895). The Creek war of 1813–1814. Chicago: Donohue&Henneberry, pp. 69–70 (accessibile for free online at Internet Archive). Halbert furtherly pointed out Claiborne's incorrect historical methods, in his article "Some Inaccuracies in Claiborne's History in Regard to Tecumseh" (cited in References below).

- ^ Sugden, "Early Pan-Indianism", in Nichols, p. 120.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 440, note 6

- ^ Drinnon, Richard (1972). White Savage: The Case of John Dunn Hunter. New York: Schocken Books.

- ^ The King of Great Britain.

- ^ Dunn Hunter, John (1824). Memoirs of a captivity among the Indians of North America, from childhood to the age of nineteen: with anecdotes descriptive of their manners and customs. London: Longman, Hurst, Orme, Brown, and Green. pp. 45–48. (accessible online in books.google)

- ^ J. Wesley Whicker (December 1921). "Shabonee's Account of Tippecanoe". Indiana Magazine of History. Bloomington: Indiana University. 17 (4): 317, 321. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- ^ Reed Beard (1911). The Battle of Tippecanoe: Historical sketches of the famous field upon which General William Henry Harrison won renown that aided him in reaching the presidency; lives of the Prophet and Tecumseh, with many interesting incidents of their rise and overthrow. The campaign of 1888 and election of General Benjamin Harrison (4th ed.). Chicago: Hammond Press. p. 44.

- ^ Madison, p. 41.

- ^ Cayton, p. 221.

- ^ Edmunds, The Shawnee Prophet, pp. 105, 110–11.

- ^ a b Langguth, p. 168

- ^ Cayton, p. 222.

- ^ Whicker, "Shabonee's Account of Tippecanoe," p. 354.

- ^ Whicker, "Shabonee's Account of Tippecanoe," p. 356.

- ^ Cayton, p. 224.

- ^ Madison and Sandweiss, p. 15.

- ^ Ehle pp. 102–4.

- ^ Pierre Burton (1980). The Invasion of Canada. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. pp. 177–82.

- ^ John Wesley Whicker (December 1922). "Tecumseh and Pushmataha". Indiana Magazine of History. Indiana University, Department of History. 18 (4): 324, 327.

- ^ John R. Elting (1995). Amateurs to Arms: A Military History of the War of 1812. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-306-80653-3.

- ^ The British official casualties for the siege of Fort Meigs were 101; their Indian allies suffered 19 casualties. The total American casualties in the siege were 986. About 630 Americans were captured, compared to 40 British. See Alec R. Gilpin (1958). The War of 1812 in the Old Northwest (1968 reprint ed.). East Lansing: The Michigan State University Press. p. 189. See also: William James (1818). A Full and Correct Account of the Military Occurrences of the Late War between Great Britain and the United States of America. I. London. pp. 188, 199–200. ISBN 0-665-35743-5. See: Ernest Cruikshank (1971) [1902]. The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in the Year 1813. Part I: January to June, 1813. New York: Arno Press. p. 297. ISBN 0-405-02838-5.

- ^ Sandy Antal (1997). A Wampum Denied: Proct[e]r's War of 1812. Carleton University Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-87013-443-4.

- ^ Gilpin, p. 187.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 337.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 335.

- ^ Norman K. Risjord (2001). Representative Americans: The Revolutionary Generation. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-7425-2075-2.

- ^ Langguth, p. 196.

- ^ Benjamin Bussey Thatcher (1832). Indian Biography, or An historical account of those individuals who have been distinguished among the North American natives as orators, warriors, statesmen and other remarkable characters. II. New York: J. and J. Harper. p. 237.

- ^ The Prophet, who observed the battle from a position behind the British line, fled on horseback after the initial charge from the American forces and remained in exile in Canada. He did not return to the United States until 1824. See Gugin and St. Clair, eds., Indiana’s 200, pp. 347–48.

- ^ Madison, p. 43.

- ^ Langguth, p. 206.

- ^ Not all tribes surrendered. Among them were the Kickapoo who had followed Tecumseh to Canada. In August 1816 more than 150 Kickapoo were still living in the Prophet's settlement at Amherstberg, where they continued their private war against the United States. Not until 1819 did the entire Canadian band of Kickapoos return south. See Arrell Morgan Gibson (1963). The Kickapoos: Lords of the Middle Border. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-8061-1264-6.

- ^ a b Mark O. Hatfield, with the Senate Historical Office (1997). "Richard Mentor Johnson (1837–1841)" (pdf). Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 121–31. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ Charles Hamilton, ed. (1950). Cry of the Thunderbird: The American Indian's Own Story. New York: Macmillan Company. p. 162.

- ^ Chapter 6, "Who Killed Tecumseh?" in Sugden, Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985), pp. 136–81.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985), p. 145.

- ^ a b Peter Dooyentate Clarke (1870). Origin and traditional history of the Wyandotts and sketches of other Indian tribes of North America, true traditional stories of Tecumseh and his league, in the years 1811 and 1812. Toronto: Hunter, Rose and Company. pp. 113–15.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985), pp. 146–47, 150.

- ^ James A. Drain Sr., "2–The Line of the Drains," in Mark L. Bardenwerper Sr., ed. (2013). Single Handed. Cambridge, Wisconsin: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1470032760.

- ^ Jason Winders (March 27, 2014). "Lecture Revisits Western's Archives and Tecumseh's Death". Western University. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- ^ Sudgen, Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985), p. 176.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985), p. 180.

- ^ Sugden, "The Dispute Over Tecumseh's Burial," Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985), pp. 215–20.

- ^ a b Madison, pp. 38–39, 43.

- ^ Madison, p. 38.

- ^ Sugden, Tecumseh (1998), p. 401; Sugden, Tecumseh's Last Stand (1985), p. 96.

- ^ Robert Remini (1991). Henry Clay. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 117. ISBN 9780393030044.

- ^ A. T. Mahan (1905). "The Negotiations at Ghent in 1814". The American Historical Review. 11 (1): 73–78.

- ^ Rich in Years: Finding Peace and Purpose in a Long Life, Johann Christophe Arnold, Plough Publishing House 2013

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (2012). The Encyclopedia Of the War Of 1812. ABC-CLIO. p. 837.

- ^ "War of 1812 hero Tecumseh commemorated on Royal Canadian Mint 25-cent circulation coin". Royal Canadian Mint. November 16, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ "Tecumseh plaque: Memorial 35035-002 Chatham, ON". National Inventory of Canadian Military Memorials. Veterans Affairs Canada. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Welland Tribune (Article ID# 2803886).

- ^ McAllister, Michael. "Underwater Archaeology". The Hamilton & Scourge National Historic Site. The City of Hamilton. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Tamanend, Chief of Delaware Indians (1628-1698), (sculpture).", Smithsonian Institution, SI.edu

- ^ WTS Memoirs, 2d ed. 11 (Lib. of America 1990)

- ^ "Tecumseh-Harrison Elementary". Vincennes Community School Corporation. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ "Tecumseh Public Schools Home Page". Tecumseh (Michigan) Public Schools. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ "Tecumseh Middle School". Tecumseh (Oklahoma) Public Schools. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ "Tecumseh Elementary School: About Us: Who was Tecumseh?". Vancouver School Board. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ "Tecumseh Public School". Halton District School Board. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ "Tecumseh Senior Public School". Toronto District School Board. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ "Photograph of a Benson John Lossing engraving of Tecumseh, based partially on a sketch by Pierre Le Dru 1812, of Tecumtha or Tecumseh with Peace Medal, undated". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b Lossing, Benson John (1868). The pictorial field-book of the war of 1812; or, illustrations, by pen and pencil, of the history, biography, scenery, relics, and traditions of the last war for American independence. Archive.org. New York City: Harper & brothers. p. 283. LCCN 08033629. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ a b Sugden, John (1985). Tecumseh's Last Stand. Google Books (Reprint 1990 ed.). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. Frontispiece. ISBN 0806122420. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ "DHH – aboriginal people in the Canadian Military". Canadian National Defence / Chief Military Personnel. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Lossing, Benson John (1868). "Chapter XIV – Campaign on the Detroit Frontier.". The pictorial field-book of the war of 1812; or, illustrations, by pen and pencil, of the history, biography, scenery, relics, and traditions of the last war for American independence. Ancestry.com. New York: Harper & Brothers. footnote of p. 283 / note 35 of Chap. XIV. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Lossing, Benson John (1868). "Chapter X – Hostilities of the Indians in the Northwest.". The pictorial field-book of the war of 1812; or, illustrations, by pen and pencil, of the history, biography, scenery, relics, and traditions of the last war for American independence. Ancestry.com. depiction of The Prophet. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ "The dying Tecumseh by Ferdinand Pettrich / American Art". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Tippecanoe County Courthouse, (sculpture) | Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution". Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ Nl.newsbank.com BYLINE:Andrew McGinn Staff Writer DATE: February 22, 2007 PUBLICATION: Springfield News-Sun (OH)

- ^ Chillicothegazette.com Archived 2014-08-08 at the Wayback Machine. 'Tecumseh' to receive award this weekend

- ^ Washington Post Allan Eckert, playwright of ‘Tecumseh!’ outdoor drama in Ohio dies at 80 in California

- ^ Historical Overview, The Battle of Tippecanoe Outdoor Drama 1990 Souvenir Program, Summer 1990.

- ^ Tecumseh at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ Seton, Ernest Thompson (2006). "IV: Wabasha". The Gospel of the Red Man: An Indian Bible. Book Tree. p. 60. ISBN 9781585092765.

- ^ Galloway, William Albert. Old Chillicothe. Xenia, OH: The Buckeye Press, 1934.

- ^ Cf. storyline of the episode Bar Wars III: The Return of Tecumseh (15 Mars 1990; Season 8, Episode 21) at IMDb (accessed 2 August 2014).

- ^ Alan Sepinwall (April 28, 2013). "Mad Men: The Floor - He had a dream". Hitfix.

- ^ "Indian Greetings". Google Answers. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

References[edit]

- Baym, Nina, Robert S. Levine, and Arnold Krupat (2007). The Norton Anthology of American Literature: Beginning to 1820. A. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393927399.

- Cayton, Andrew R. L. (1996). Frontier Indiana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253330483.

- Drake, Benjamin (1841). Life of Tecumseh, and His Brother the Prophet: With a Historical Sketch of the Shawanoe Indians. E. Morgan and Company.

- Edmunds, R. David (1985). The Shawnee Prophet. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1850-8.

- Gugin, Linda C., and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press and the Indiana Historical Bureau. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.

- Gugin, Linda C., and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 346–48. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.