Theology

| Part of a series on |

| God |

|---|

|

In particular religions |

|

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the Divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries.[1] It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the supernatural, but also deals with religious epistemology, asks and seeks to answer the question of revelation. Revelation pertains to the acceptance of God, gods, or deities, as not only transcendent or above the natural world, but also willing and able to interact with the natural world and, in particular, to reveal themselves to humankind. While theology has turned into a secular field, religious adherents still consider theology to be a discipline that helps them live and understand concepts such as life and love and that helps them lead lives of obedience to the deities they follow or worship.

Etymology[edit]

Theology is derived from the Greek theologia (θεολογία), which derived from theos (Θεός), meaning "god", and -logia (-λογία),[2][3] meaning "utterances, sayings, or oracles" (a word related to logos [λόγος], meaning "word, discourse, account, or reasoning") which had passed into Latin as theologia and into French as théologie. The English equivalent "theology" (Theologie, Teologye) had evolved by 1362.[4] The sense the word has in English depends in large part on the sense the Latin and Greek equivalents had acquired in patristic and medieval Christian usage, although the English term has now spread beyond Christian contexts.

Definition[edit]

Augustine of Hippo define the Latin equivalent, theologia, as "reasoning or discussion concerning the Deity";[5] Richard Hooker defined "theology" in English as "the science of things divine".[6] The term can, however, be used for a variety of disciplines or fields of study.[7]

Theology considers whether the divine exists in some form, such as in physical, supernatural, mental, or social realities, and what evidence for and about it may be found via personal spiritual experiences or historical records of such experiences as documented by others. The study of these assumptions is not part of theology proper but is found in the philosophy of religion, and increasingly through the psychology of religion and neurotheology. Theology then aims to structure and understand these experiences and concepts, and to use them to derive normative prescriptions for how to live our lives.

Theologians use various forms of analysis and argument (experiential, philosophical, ethnographic, historical, and others) to help understand, explain, test, critique, defend or promote any myriad of religious topics. As in philosophy of ethics and case law, arguments often assume the existence of previously resolved questions, and develop by making analogies from them to draw new inferences in new situations.

The study of theology may help a theologian more deeply understand their own religious tradition,[8] another religious tradition,[9] or it may enable them to explore the nature of divinity without reference to any specific tradition. Theology may be used to propagate,[10] reform,[11] or justify a religious tradition or it may be used to compare,[12] challenge (e.g. biblical criticism), or oppose (e.g. irreligion) a religious tradition or world-view. Theology might also help a theologian address some present situation or need through a religious tradition,[13] or to explore possible ways of interpreting the world.[14]

History[edit]

Greek theologia (θεολογία) was used with the meaning "discourse on God" around 380 BC by Plato in The Republic, Book ii, Ch. 18.[15] Aristotle divided theoretical philosophy into mathematike, physike and theologike, with the last corresponding roughly to metaphysics, which, for Aristotle, included discourse on the nature of the divine.[16]

Drawing on Greek Stoic sources, the Latin writer Varro distinguished three forms of such discourse: mythical (concerning the myths of the Greek gods), rational (philosophical analysis of the gods and of cosmology) and civil (concerning the rites and duties of public religious observance).[17]

Some Latin Christian authors, such as Tertullian and Augustine, followed Varro's threefold usage,[18] though Augustine also used the term more simply to mean 'reasoning or discussion concerning the deity'[5]

In patristic Greek Christian sources, theologia could refer narrowly to devout and inspired knowledge of, and teaching about, the essential nature of God.[19]

The Latin author Boethius, writing in the early 6th century, used theologia to denote a subdivision of philosophy as a subject of academic study, dealing with the motionless, incorporeal reality (as opposed to physica, which deals with corporeal, moving realities).[20] Boethius' definition influenced medieval Latin usage.[21]

In scholastic Latin sources, the term came to denote the rational study of the doctrines of the Christian religion, or (more precisely) the academic discipline which investigated the coherence and implications of the language and claims of the Bible and of the theological tradition (the latter often as represented in Peter Lombard's Sentences, a book of extracts from the Church Fathers).[22]

In the Renaissance, especially with Florentine Platonist apologists of Dante's poetics, the distinction between "poetic theology" (theologia poetica) and "revealed" or Biblical theology serves as steppingstone for a revival of philosophy as independent of theological authority.

It is in this last sense, theology as an academic discipline involving rational study of Christian teaching, that the term passed into English in the fourteenth century,[23] although it could also be used in the narrower sense found in Boethius and the Greek patristic authors, to mean rational study of the essential nature of God – a discourse now sometimes called theology proper.[24]

From the 17th century onwards, it also became possible to use the term theology to refer to study of religious ideas and teachings that are not specifically Christian (e.g., in the term natural theology which denoted theology based on reasoning from natural facts independent of specifically Christian revelation,[25]) or that are specific to another religion (see below).

"Theology" can also now be used in a derived sense to mean "a system of theoretical principles; an (impractical or rigid) ideology".[26]

In various religions[edit]

The term theology has been deemed by some as only appropriate to the study of religions that worship a supposed deity (a theos), i.e. more widely than monotheism; and presuppose a belief in the ability to speak and reason about this deity (in logia). They suggest the term is less appropriate in religious contexts that are organized differently (religions without a single deity, or that deny that such subjects can be studied logically). ("Hierology" has been proposed as an alternative, more generic term.[27])

Abrahamic religions[edit]

Christianity[edit]

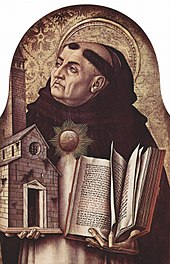

As defined by Thomas Aquinas, theology is constituted by a triple aspect: what is taught by God, teaches of God and leads to God (Latin: Theologia a Deo docetur, Deum docet, et ad Deum ducit).[28] This indicates the three distinct areas of God as theophanic revelation, the systematic study of the nature of divine and, more generally, of religious belief, and the spiritual path. Christian theology as the study of Christian belief and practice concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and the New Testament as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theologians use biblical exegesis, rational analysis and argument. Theology might be undertaken to help the theologian better understand Christian tenets, to make comparisons between Christianity and other traditions, to defend Christianity against objections and criticism, to facilitate reforms in the Christian church, to assist in the propagation of Christianity, to draw on the resources of the Christian tradition to address some present situation or need, or for a variety of other reasons.

Islam[edit]

Islamic theological discussion that parallels Christian theological discussion is called Kalam; the Islamic analogue of Christian theological discussion would more properly be the investigation and elaboration of Sharia or Fiqh.

Kalam ... does not hold the leading place in Muslim thought that theology does in Christianity. To find an equivalent for 'theology' in the Christian sense it is necessary to have recourse to several disciplines, and to the usul al-fiqh as much as to kalam. (L. Gardet)[29]

Judaism[edit]

In Jewish theology, the historical absence of political authority has meant that most theological reflection has happened within the context of the Jewish community and synagogue, including through rabbinical discussion of Jewish law and Midrash (rabbinic biblical commentaries). Jewish theology is linked to ethics and therefore has implications for how one behaves.[30][31]

Indian religions[edit]

Buddhism[edit]

Some academic inquiries within Buddhism, dedicated to the investigation of a Buddhist understanding of the world, prefer the designation Buddhist philosophy to the term "Buddhist theology", since Buddhism lacks the same conception of a theos. Jose Ignacio Cabezon, who argues that the use of "theology" is appropriate, can only do so, he says, because "I take theology not to be restricted to discourse on God ... I take 'theology' not to be restricted to its etymological meaning. In that latter sense, Buddhism is of course atheological, rejecting as it does the notion of God."[32]

Hinduism[edit]

Within Hindu philosophy, there is a tradition of philosophical speculation on the nature of the universe, of God (termed "Brahman", Paramatma and Bhagavan in some schools of Hindu thought) and of the Atman (soul). The Sanskrit word for the various schools of Hindu philosophy is Darshana (meaning "view" or "viewpoint"). Vaishnava theology has been a subject of study for many devotees, philosophers and scholars in India for centuries. A large part of its study lies in classifying and organizing the manifestations of thousands of gods and their aspects. In recent decades the study of Hinduism has also been taken up by a number of academic institutions in Europe, such as the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies and Bhaktivedanta College.[33] See also: Krishnology

Other[edit]

Shinto[edit]

In Japan, the term "theology" (神学, shingaku) has been ascribed to Shinto since the Edo period with the publication of Mano Tokitsuna's Kokon shingaku ruihen (古今神学類編; lit. "categorized compilation of ancient theology"). In modern times, other terms are used to denote studies in Shinto--as well as Buddhist--belief, such as kyōgaku (教学; "education [and] studies") and shūgaku (宗学; "religion studies").

Modern Paganism[edit]

English academic Graham Harvey has commented that Pagans "rarely indulge in theology".[34] Nevertheless, theology has been applied in some sectors across contemporary Pagan communities, including Wicca, Heathenry, Druidry and Kemetism. As these religions have given precedence to orthopraxy, theological views often vary among adherents.

The term is used by Christine Kraemer in her book Seeking The Mystery: An Introduction to Pagan Theologies and by Michael York in Pagan Theology: Paganism as a World Religion.

Topics[edit]

As an academic discipline[edit]

The history of the study of theology in institutions of higher education is as old as the history of such institutions themselves. For instance, Taxila was an early centre of Vedic learning, possible from the 6th century BC or earlier;[35] the Platonic Academy founded in Athens in the 4th century BC seems to have included theological themes in its subject matter;[36] the Chinese Taixue delivered Confucian teaching from the 2nd century BC;[37] the School of Nisibis was a centre of Christian learning from the 4th century AD;[38][39] Nalanda in India was a site of Buddhist higher learning from at least the 5th or 6th century AD;[40] and the Moroccan University of Al-Karaouine was a centre of Islamic learning from the 10th century,[41] as was Al-Azhar University in Cairo.[42]

The earliest universities were developed under the aegis of the Latin Church by papal bull as studia generalia and perhaps from cathedral schools. It is possible, however, that the development of cathedral schools into universities was quite rare, with the University of Paris being an exception.[43] Later they were also founded by Kings (University of Naples Federico II, Charles University in Prague, Jagiellonian University in Kraków) or municipal administrations (University of Cologne, University of Erfurt). In the early medieval period, most new universities were founded from pre-existing schools, usually when these schools were deemed to have become primarily sites of higher education. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by monasteries.[44] Christian theological learning was therefore a component in these institutions, as was the study of Church or Canon law: universities played an important role in training people for ecclesiastical offices, in helping the church pursue the clarification and defence of its teaching, and in supporting the legal rights of the church over against secular rulers.[45] At such universities, theological study was initially closely tied to the life of faith and of the church: it fed, and was fed by, practices of preaching, prayer and celebration of the Mass.[46]

During the High Middle Ages, theology was therefore the ultimate subject at universities, being named "The Queen of the Sciences" and serving as the capstone to the Trivium and Quadrivium that young men were expected to study. This meant that the other subjects (including Philosophy) existed primarily to help with theological thought.[47]

Christian theology's preeminent place in the university began to be challenged during the European Enlightenment, especially in Germany.[48] Other subjects gained in independence and prestige, and questions were raised about the place of a discipline that seemed to involve commitment to the authority of particular religious traditions in institutions that were increasingly understood to be devoted to independent reason.[49]

Since the early nineteenth century, various different approaches have emerged in the West to theology as an academic discipline. Much of the debate concerning theology's place in the university or within a general higher education curriculum centres on whether theology's methods are appropriately theoretical and (broadly speaking) scientific or, on the other hand, whether theology requires a pre-commitment of faith by its practitioners, and whether such a commitment conflicts with academic freedom.[50]

Ministerial training[edit]

In some contexts, theology has been held to belong in institutions of higher education primarily as a form of professional training for Christian ministry. This was the basis on which Friedrich Schleiermacher, a liberal theologian, argued for the inclusion of theology in the new University of Berlin in 1810.[51]

For instance, in Germany, theological faculties at state universities are typically tied to particular denominations, Protestant or Roman Catholic, and those faculties will offer denominationally-bound (konfessionsgebunden) degrees, and have denominationally bound public posts amongst their faculty; as well as contributing 'to the development and growth of Christian knowledge' they 'provide the academic training for the future clergy and teachers of religious instruction at German schools.'[52]

In the United States, several prominent colleges and universities were started in order to train Christian ministers. Harvard,[53] Georgetown,[54] Boston University, Yale,[55] Duke University[56], and Princeton[57] all had the theological training of clergy as a primary purpose at their foundation.

Seminaries and bible colleges have continued this alliance between the academic study of theology and training for Christian ministry. There are, for instance, numerous prominent examples in the United States, including Catholic Theological Union in Chicago,[58] The Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley,[59] Criswell College in Dallas,[60] The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville,[61] Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois,[62] Andersonville Theological Seminary in Camilla, Georgia,[63] Dallas Theological Seminary,[64] North Texas Collegiate Institute in Farmers Branch, Texas[65] and the Assemblies of God Theological Seminary in Springfield, Missouri.

As an academic discipline in its own right[edit]

In some contexts, scholars pursue theology as an academic discipline without formal affiliation to any particular church (though members of staff may well have affiliations to churches), and without focussing on ministerial training. This applies, for instance, to many university departments in the United Kingdom, including the Faculty of Divinity at the University of Cambridge, the Department of Theology and Religion at the University of Exeter, and the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of Leeds.[66] Traditional academic prizes, such as the University of Aberdeen's Lumsden and Sachs Fellowship, tend to acknowledge performance in theology (or divinity as it is known at Aberdeen) and in religious studies.

Religious studies[edit]

In some contemporary contexts, a distinction is made between theology, which is seen as involving some level of commitment to the claims of the religious tradition being studied, and religious studies, which by contrast is normally seen as requiring that the question of the truth or falsehood of the religious traditions studied be kept outside its field. Religious studies involves the study of historical or contemporary practices or of those traditions' ideas using intellectual tools and frameworks that are not themselves specifically tied to any religious tradition and that are normally understood to be neutral or secular.[67] In contexts where 'religious studies' in this sense is the focus, the primary forms of study are likely to include:

- Anthropology of religion

- Comparative religion

- History of religions

- Philosophy of religion

- Psychology of religion

- Sociology of religion

Sometimes, theology and religious studies are seen as being in tension,[68] and at other times, they are held to coexist without serious tension.[69] Occasionally it is denied that there is as clear a boundary between them.[70]

Criticism[edit]

Before the 20th century[edit]

Whether or not reasoned discussion about the divine is possible has long been a point of contention. Protagoras, as early as the fifth century BC, who is reputed to have been exiled from Athens because of his agnosticism about the existence of the gods, said that "Concerning the gods I cannot know either that they exist or that they do not exist, or what form they might have, for there is much to prevent one's knowing: the obscurity of the subject and the shortness of man's life."[71]

Since at least the eighteenth century, various authors have criticized the suitability of theology as an academic discipline.[72] In 1772, Baron d'Holbach labeled theology "a continual insult to human reason" in Le Bon sens.[72] Lord Bolingbroke, an English politician and political philosopher, wrote in Section IV of his Essays on Human Knowledge, "Theology is in fault not religion. Theology is a science that may justly be compared to the Box of Pandora. Many good things lie uppermost in it; but many evil lie under them, and scatter plagues and desolation throughout the world."[73]

Thomas Paine, a Deistic American political theorist and pamphleteer, wrote in his three-part work The Age of Reason (published in 1794, 1795, and 1807), "The study of theology, as it stands in Christian churches, is the study of nothing; it is founded on nothing; it rests on no principles; it proceeds by no authorities; it has no data; it can demonstrate nothing; and it admits of no conclusion. Not anything can be studied as a science, without our being in possession of the principles upon which it is founded; and as this is the case with Christian theology, it is therefore the study of nothing."[74]

The German atheist philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach sought to dissolve theology in his work Principles of the Philosophy of the Future: "The task of the modern era was the realization and humanization of God – the transformation and dissolution of theology into anthropology."[75] This mirrored his earlier work The Essence of Christianity (pub. 1841), for which he was banned from teaching in Germany, in which he had said that theology was a "web of contradictions and delusions".[76]

The American satirist Mark Twain remarked in his essay "The Lowest Animal", originally written in around 1896, but not published until after Twain's death in 1910,[77] that "[Man] is the only animal that loves his neighbor as himself and cuts his throat if his theology isn't straight. He has made a graveyard of the globe in trying his honest best to smooth his brother's path to happiness and heaven... The higher animals have no religion. And we are told that they are going to be left out in the Hereafter. I wonder why? It seems questionable taste."[77][78]

20th and 21st centuries[edit]

A.J. Ayer, a British former logical-positivist, sought to show in his essay "Critique of Ethics and Theology" that all statements about the divine are nonsensical and any divine-attribute is unprovable. He wrote: "It is now generally admitted, at any rate by philosophers, that the existence of a being having the attributes which define the god of any non-animistic religion cannot be demonstratively proved... [A]ll utterances about the nature of God are nonsensical."[79]

The Jewish atheist philosopher Walter Kaufmann, in his essay "Against Theology", sought to differentiate theology from religion in general. "Theology, of course, is not religion; and a great deal of religion is emphatically anti-theological... An attack on theology, therefore, should not be taken as necessarily involving an attack on religion. Religion can be, and often has been, untheological or even anti-theological." However, Kaufmann found that "Christianity is inescapably a theological religion".[80]

The English atheist Charles Bradlaugh believed theology prevented human beings from achieving liberty,[81] although he also noted that many theologians of his time held that, because modern scientific research sometimes contradicts sacred scriptures, the scriptures must therefore be wrong.[82] Robert G. Ingersoll, an American agnostic lawyer, stated that, when theologians had power, the majority of people lived in hovels, while a privileged few had palaces and cathedrals. In Ingersoll's opinion, it was science that improved people's lives, not theology. Ingersoll further maintained that trained theologians reason no better than a person who assumes the devil must exist because pictures resemble the devil so exactly.[83]

The British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins has been an outspoken critic of theology.[72][84] In an article published in The Independent in 1993, he severely criticizes theology as entirely useless,[84] declaring that it has completely and repeatedly failed to answer any questions about the nature of reality or the human condition.[84] He states, "I have never heard any of them [i.e. theologians] ever say anything of the smallest use, anything that was not either platitudinously obvious or downright false."[84] He then states that, if all theology were completely eradicated from the earth, no one would notice or even care.[84] He concludes: "The achievements of theologians don't do anything, don't affect anything, don't achieve anything, don't even mean anything. What makes you think that 'theology' is a subject at all?"[84]

References[edit]

- ^ "theology". Wordnetweb.princeton.edu. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ The accusative plural of the neuter noun λόγιον; cf. Walter Bauer, William F. Arndt, F. Wilbur Gingrich, Frederick W. Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament, 2nd ed., (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 476. For examples of λόγια in the New Testament, cf. Acts 7:38; Romans 3:2; 1 Peter 4:11.

- ^ See Constantine B. Scouteris, Ἡ ἔννοια τῶν ὅρων "Θεολογία", "Θεολογεῖν", "Θεολόγος", ἐν τῇ διδασκαλίᾳ τῶν Ἑλλήνων Πατέρων καί Ἐκκλησιαστικῶν συγγραφέων μέχρι καί τῶν Καππαδοκῶν, Ἀθῆναι 1972, pp. 187 - Αναδημοσίευση στη νέα ελληνική 2016 [The Meaning of the Terms "Theology", "to Theologize" and "Theologian" in the Teaching of the Greek Fathers up to and Including the Cappadocians; (in Greek), Athens 1972, pp. 187 - Republication in 2016].

- ^ Langland, Piers Plowman A ix 136

- ^ a b City of God Book VIII. i. "de divinitate rationem sive sermonem" Archived 4 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "''Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity'', 3.8.11" (PDF). Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ McGrath, Alister. 1998. Historical Theology: An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 1–8.

- ^ See, e.g., Daniel L. Migliore, Faith Seeking Understanding: An Introduction to Christian Theology 2nd ed.(Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004)

- ^ See, e.g., Michael S. Kogan, 'Toward a Jewish Theology of Christianity' in The Journal of Ecumenical Studies 32.1 (Winter 1995), 89–106; available online at [1] Archived 15 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See, e.g., Duncan Dormor et al (eds), Anglicanism, the Answer to Modernity (London: Continuum, 2003)

- ^ See, e.g., John Shelby Spong, Why Christianity Must Change or Die (New York: Harper Collins, 2001)

- ^ See, e.g., David Burrell, Freedom and Creation in Three Traditions (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1994)

- ^ See, e.g., Timothy Gorringe, Crime, Changing Society and the Churches Series (London:SPCK, 2004)

- ^ See e.g., Anne Hunt Overzee's gloss upon the view of Ricœur (1913–2005) as to the role and work of 'theologian': "Paul Ricœur speaks of the theologian as a hermeneut, whose task is to interpret the multivalent, rich metaphors arising from the symbolic bases of tradition so that the symbols may 'speak' once again to our existential situation." Anne Hunt Overzee The body divine: the symbol of the body in the works of Teilhard de Chardin and Rāmānuja, Cambridge studies in religious traditions 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), ISBN 0-521-38516-4, ISBN 978-0-521-38516-9, p.4; Source: [2] (accessed: Monday 5 April 2010)

- ^ Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon''.

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book Epsilon. Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ As cited by Augustine, City of God, Book 6, ch.5.

- ^ See Augustine, City of God, Book 6, ch.5. and Tertullian, Ad Nationes, Book 2, ch.1.

- ^ Gregory of Nazianzus uses the word in this sense in his fourth-century Theological Orations; after his death, he was called "the Theologian" at the Council of Chalcedon and thereafter in Eastern Orthodoxy—either because his Orationswere seen as crucial examples of this kind of theology, or in the sense that he was (like the author of the Book of Revelation) seen as one who was an inspired preacher of the words of God. (It is unlikely to mean, as claimed in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers introduction to his Theological Orations, that he was a defender of the divinity of Christ the Word.) See John McGukin, Saint Gregory of Nazianzus: An Intellectual Biography (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2001), p.278.

- ^ "Boethius, On the Holy Trinity" (PDF). Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ G.R. Evans, Old Arts and New Theology: The Beginnings of Theology as an Academic Discipline (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980), 31–32.

- ^ See the title of Peter Abelard's Theologia Christiana, and, perhaps most famously, of Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica

- ^ See the 'note' in the Oxford English Dictionary entry for 'theology'.

- ^ See, for example, Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology, vol. 1, part 1 (1871).

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, sense 1

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1989 edition, 'Theology' sense 1(d), and 'Theological' sense A.3; the earliest reference given is from the 1959 Times Literary Supplement 5 June 329/4: "The 'theological' approach to Soviet Marxism ... proves in the long run unsatisfactory."

- ^ E.g., by Count E. Goblet d'Alviella in 1908; see Alan H. Jones, Independence and Exegesis: The Study of Early Christianity in the Work of Alfred Loisy (1857–1940), Charles Guignebert (1857 [i.e. 1867]–1939), and Maurice Goguel (1880–1955) (Mohr Siebeck, 1983), p.194.

- ^ Kapic, Kelly M. Kapic (2012). A Little Book for New Theologians. Why and How to Study Theology. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-830-86670-0.

- ^ L. Gardet, 'Ilm al-kalam' in The Encyclopedia of Islam, ed. P.J. Bearman et al (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 1999).

- ^ Libenson, Dan and Lex Rofeberg, hosts. "God and Gender - Rachel Adler." Judaism Unbound, episode 138, 5 Oct. 2018.

- ^ Randi Rashkover, 'A Call for Jewish Theology', Crosscurrents, Winter 1999, starts by saying, "Frequently the claim is made that, unlike Christianity, Judaism is a tradition of deeds and maintains no strict theological tradition. Judaism's fundamental beliefs are inextricable from their halakhic observance (that set of laws revealed to Jews by God), embedded and presupposed by that way of life as it is lived and learned."

- ^ Jose Ignacio Cabezon, 'Buddhist Theology in the Academy' in Roger Jackson and John J. Makransky's Buddhist Theology: Critical Reflections by Contemporary Buddhist Scholars (London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 25–52.

- ^ See Anna S. King, 'For Love of Krishna: Forty Years of Chanting' in Graham Dwyer and Richard J. Cole, The Hare Krishna Movement: Forty Years of Chant and Change (London/New York: I.B. Tauris, 2006), pp. 134–167: p. 163, which describes developments in both institutions, and speaks of Hare Krishna devotees 'studying Vaishnava theology and practice in mainstream universities.'

- ^ Graham, Harvey (2007). Listening People, Speaking Earth: Contemporary Paganism (second ed.). London: Hurst & Company. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-85065-272-4.

- ^ Timothy Reagan, Non-Western Educational Traditions: Alternative Approaches to Educational Thought and Practice, 3rd edition (Lawrence Erlbaum: 2004), p.185 and Sunna Chitnis, 'Higher Education' in Veena Das (ed), The Oxford India Companion to Sociology and Social Anthropology (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 1032–1056: p.1036 suggest an early date; a more cautious appraisal is given in Hartmut Scharfe, Education in Ancient India (Leiden: Brill, 2002), pp. 140–142.

- ^ John Dillon, The Heirs of Plato: A Study in the Old Academy, 347–274BC (Oxford: OUP, 2003)

- ^ Xinzhong Yao, An Introduction to Confucianism (Cambridge: CUP, 2000), p.50.

- ^ Becker, Adam H. (2006). The Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom: The School of Nisibis and the Development of Scholastic Culture in Late Antique Mesopotamia. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ "The School of Nisibis". Nestorian.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ Hartmut Scharfe, Education in Ancient India (Leiden: Brill, 2002), p.149.

- ^ The Al-Qarawiyyin mosque was founded in 859 AD, but 'While instruction at the mosque must have begun almost from the beginning, it is only ... by the end of the tenth-century that its reputation as a center of learning in both religious and secular sciences ... must have begun to wax.' Y. G-M. Lulat, A History of African Higher Education from Antiquity to the Present: A Critical Synthesis (Greenwood, 2005), p.71

- ^ Andrew Beattie, Cairo: A Cultural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), p.101.

- ^ Gordon Leff, Paris and Oxford Universities in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. An Institutional and Intellectual History, Wiley, 1968.

- ^ Johnson, P. (2000). The Renaissance : a short history. Modern Library chronicles (Modern Library ed.). New York: Modern Library, p. 9.

- ^ Walter Rüegg, "Themes" in Walter Rüegg, A History of the University in Europe, vol.1, ed. H. de Ridder-Symoens, Universities in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 3–34: pp. 15–16.

- ^ See Gavin D'Costa, Theology in the Public Square: Church, Academy and Nation (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), ch.1.

- ^ Thomas Albert Howard, Protestant Theology and the Making of the Modern German University (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), p.56: '[P]hilosophy, the scientia scientarum in one sense, was, in another, portrayed as the humble "handmaid of theology".'

- ^ See Thomas Albert Howard, Protestant Theology and the Making of the Modern German University (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006):

- ^ See Thomas Albert Howard's work already cited, and his discussion of, for instance, Immanuel Kant's Conflict of the Faculties (1798), and J.G. Fichte's Deduzierter Plan einer zu Berlin errichtenden höheren Lehranstalt (1807).

- ^ See Thomas Albert Howard, Protestant Theology and the Making of the Modern German University (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Hans W. Frei, Types of Christian Theology, ed. William C. Placher and George Hunsinger (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992); Gavin D'Costa, Theology in the Public Square: Church, Academy and Nation (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005); James W. McClendon, Systematic Theology 3: Witness (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2000), ch.10: 'Theology and the University'.

- ^ Friedrich Schleiermacher, Brief Outline of Theology as a Field of Study, 2nd edition, tr. Terrence N. Tice (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 1990); Thomas Albert Howard, Protestant Theology and the Making of the Modern German University (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), ch.14.

- ^ Reinhard G. Kratz, 'Academic Theology in Germany', Religion 32.2 (2002): pp.113–116.

- ^ 'The primary purpose of Harvard College was, accordingly, the training of clergy.' But 'the school served a dual purpose, training men for other professions as well.' George M. Marsden, The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), p.41.

- ^ Georgetown was a Jesuit institution founded in significant part to provide a pool of educated Catholics some of whom who could go on to full seminary training for the priesthood. See Robert Emmett Curran, Leo J. O'Donovan, The Bicentennial History of Georgetown University: From Academy to University 1789–1889 (Georgetown: Georgetown University Press, 1961), Part One.

- ^ Yale's original 1701 charter speaks of the purpose being 'Sincere Regard & Zeal for upholding & Propagating of the Christian Protestant Religion by a succession of Learned & Orthodox' and that 'Youth may be instructed in the Arts and Sciences (and) through the blessing of Almighty God may be fitted for Publick employment both in Church and Civil State.' 'The Charter of the Collegiate School, October 1701' in Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Documentary History of Yale University, Under the Original Charter of the Collegiate School of Connecticut 1701–1745 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1916); available online at [1]

- ^ Duke University Libraries. "Duke University: A Brief Narrative History". Duke University Libraries. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ At Princeton, one of the founders (probably Ebeneezer Pemberton) wrote in c.1750, 'Though our great Intention was to erect a seminary for educating Ministers of the Gospel, yet we hope it will be useful in other learned professions – Ornaments of the State as Well as the Church. Therefore we propose to make the plan of Education as extensive as our Circumstances will admit.' Quoted in Alexander Leitch, A Princeton Companion (Princeton University Press, 1978).

- ^ "The CTU Story". Catholic Theological Union. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

lay men and women, religious sisters and brothers, and seminarians have studied alongside one another, preparing to serve God's people

- ^ See 'About the GTU' at The Graduate Theological Union website (Retrieved 29 August 2009): 'dedicated to educating students for teaching, research, ministry, and service.'

- ^ "The Criswell Vision". Criswell College. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

Criswell College exists to serve the churches of our Lord Jesus Christ by developing God-called men and women in the Word (intellectually and academically) and by the Word (professionally and spiritually) for authentic ministry leadership

- ^ "Mission Statement". Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

the mission of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary is ... to be a servant of the churches of the Southern Baptist Convention by training, educating, and preparing ministers of the gospel for more faithful service

- ^ "About Trinity Evangelical Divinity School". Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

Trinity Evangelical Divinity School (TEDS) is a learning community dedicated to the development of servant leaders for the global church, leaders who are spiritually, biblically, and theologically prepared to engage contemporary culture for the sake of Christ's kingdom

- ^ ATS. "Doctoral Programs Student Catalog & Handbook". Andersonvilleseminary.com. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ See 'About DTS' at the Dallas Theological Seminary website (Retrieved 29 August 2009): 'At Dallas, the scholarly study of biblical and related subjects is inseparably fused with the cultivation of the spiritual life. All this is designed to prepare students to communicate the Word of God in the power of the Spirit of God.'

- ^ ".::North Texas Collegiate Institute ::". .::North Texas Collegiate Institute ::.

- ^ See the 'Why Study Theology?' Archived 9 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine page at the University of Exeter (Retrieved 1 September 2009), and the 'About us' page at the University of Leeds. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 August 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ See, for example, Donald Wiebe, The Politics of Religious Studies: The Continuing Conflict with Theology in the Academy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000).

- ^ See K.L. Knoll, 'The Ethics of Being a Theologian', Chronicle of Higher Education, 27 July 2009.

- ^ See David Ford, 'Theology and Religious Studies for a Multifaith and Secular Society' in D.L. Bird and Simon G. Smith (eds), Theology and Religious Studies in Higher Education (London: Continuum, 2009).

- ^ Timothy Fitzgerald, The Ideology of Religious Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- ^ Protagoras, fr.4, from On the Gods, tr. Michael J. O'Brien in The Older Sophists, ed. Rosamund Kent Sprague (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1972), 20, emphasis added. Cf. Carol Poster, "Protagoras (fl. 5th C. BCE)" in The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy; accessed: 6 October 2008.

- ^ a b c Loughlin, Gerard (2009). "11- Theology in the university". In Ker, John; Merrigan, Terrance (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to John Henry Newman. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–240. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521871860.011. ISBN 9780521871860.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ^ The philosophical works of Lord Bolingbroke Volume 3, p. 396

- ^ Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, from "The Life and Major Writings of Thomas Paine", ed. Philip S. Foner, (New York, The Citadel Press, 1945) p. 601.

- ^ Ludwig Feuerbach, Principles of the Philosophy of the Future, trans. Manfred H. Vogel, (Indianapolis, Hackett Publishing Company, 1986) p5

- ^ Ludwig Feuerbach, The Essence of Christianity, trans. George Eliot, (Amherst, New York, Prometheus Books, 1989) Preface, XVI.

- ^ a b Twain, Mark (1896). "The Lowest Animal". thoughtco.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ^ "Directory of Mark Twain's maxims, quotations, and various opinions". Twainquotes.com. 28 November 1902. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ A.J. Ayer, Language, Truth and Logic, (New York, Dover Publications, 1936) pp. 114–115.

- ^ Walter Kaufmann, The Faith of a Heretic, (Garden City, New York, Anchor Books, 1963) pp. 114, 127–128, 130.

- ^ "Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891)". Positiveatheism.org. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Humanity's Gain from Unbelief". Positiveatheism.org. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Robert Green Ingersoll". Positiveatheism.org. 11 August 1954. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Dawkin, Richard (20 March 1993). "Letter: Scientific versus theological knowledge". The Independent.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links[edit]

| Library resources about Theology |

| Look up theology in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Theology |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theology. |

- "Theology" on Encyclopædia Britannica

- Chattopadhyay, Subhasis. "Reflections on Hindu Theology" in Prabuddha Bharata or Awakened India 120(12):664-672 (2014). ISSN 0032-6178. Edited by Swami Narasimhananda.

Theology public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Theology public domain audiobook at LibriVox