The Wall

| The Wall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 30 November 1979 | |||

| Recorded | December 1978 – November 1979 | |||

| Studio | Various

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 80:02 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | ||||

| Pink Floyd chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Wall | ||||

| ||||

The Wall is the eleventh studio album by English rock band Pink Floyd, released 30 November 1979 on Harvest and Columbia Records. It is a rock opera that explores Pink, a jaded rockstar whose eventual self-imposed isolation from society is symbolized by a wall. The album was a commercial success, topping the US charts for 15 weeks, and reaching number three in the UK. It initially received mixed reviews from critics, many of whom found it overblown and pretentious, but later came to be considered one of the greatest albums of all time.

Bassist Roger Waters conceived The Wall during Pink Floyd's 1977 In The Flesh tour, modeling the character of Pink after himself and former bandmate Syd Barrett. Recording spanned from December 1978 to November 1979. Producer Bob Ezrin helped to refine the concept and bridge tensions during recording, as the band were struggling with personal and financial issues at the time. The Wall is the last album to feature Pink Floyd as a quartet; keyboardist Richard Wright was fired by Waters during production, but stayed on as a salaried musician. Three singles were issued from the album: "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" (the band's only US number-one single), "Run Like Hell", and "Comfortably Numb". From 1980 to 1981, Pink Floyd performed the full album on a tour that featured elaborate theatrical effects.

The Wall was adapted into a 1982 feature film of the same name and remains one of the best-known concept albums.[4]. The album has sold more than 24 million copies, is the second best-selling in the band's catalog, behind The Dark Side of the Moon, and is one of the best-selling of all time. Some of the outtakes from the recording sessions were later used on the group's next album, The Final Cut (1983). In 2000 it was voted number 30 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums.[5] In 2003, Rolling Stone listed The Wall at number 87 on its list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". From 2010 to 2013, Waters staged a new Wall live tour that became the highest-grossing tour by a solo musician.

Background[edit]

In 1977, Pink Floyd played the In the Flesh Tour, their first playing in stadiums. Bassist and songwriter Roger Waters disliked the experience, feeling the audience was not listening and that many were too far away to see the band. He said: "It became a social event rather than a more controlled and ordinary relationship between musicians and an audience."[6] Some audience members set off firecrackers, leading Waters to stop playing and scold them. In July 1977, on the final date at the Montreal Olympic Stadium, a group of noisy and excited fans near the stage irritated Waters so much that he spat at one of them.[7]

Guitarist David Gilmour refused to perform a final encore and sat at the soundboard,[8] leaving the band, with backup guitarist Snowy White, to improvise a slow, sad 12-bar blues, which Waters announced to the audience as "some music to go home to".[9][10] That night, Waters spoke with producer Bob Ezrin and Ezrin's psychiatrist friend about the alienation he was experiencing. He articulated his desire to isolate himself by constructing a wall across the stage between the performers and the audience.[11]

While Gilmour and Wright were in France recording solo albums, and drummer Nick Mason was busy producing Steve Hillage's Green, Waters began to write material.[12] The spitting incident became the starting point for a new concept, which explored the protagonist's self-imposed isolation after years of traumatic interactions with authority figures and the loss of his father as a child.[10]

In July 1978, Pink Floyd reconvened at Britannia Row Studios, where Waters presented two new ideas for concept albums. The first was a 90-minute demo with the working title Bricks in the Wall.[13] The second was about a man's dreams across one night, and dealt with marriage, sex, and the pros and cons of monogamy and family life versus promiscuity.[14] The band chose the first option; the second eventually became Waters's first solo album, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking (1984).[13]

By September, Pink Floyd were having financial problems and urgently needed to produce an album to make money.[15] Financial planners Norton Warburg Group (NWG) had invested £1.3–3.3 million, up to £19.1 million in contemporary value,[16] of the group's money in high-risk venture capital to reduce their tax liabilities. The strategy failed when many of the businesses NWG invested in lost money, leaving the band facing tax rates potentially as high as 83 percent. "We made Dark Side and it looked as if we'd cracked it," recalled Waters. "Then suddenly these bastards had stolen it all. It looked as if we might be faced with huge tax bills for the money that had been lost. Eighty-three per cent was a lot of money in those days and we didn't have it."[17] Pink Floyd terminated their relationship with NWG, demanding the return of uninvested funds.[18][nb 1] "By force of necessity, I had to become closely involved in the business side," said Gilmour, "because no one around us has shown themselves sufficiently capable or honest to cope with it, and I saw with Norton Warburg that the shit was heading inexorably towards the fan. They weren't the first crooks we stupidly allied ourselves with. Ever since then, there's not a penny that I haven't signed for. I sign every cheque and examine everything."[17]

To help manage the project's 26 tracks, Waters decided to bring in a producer and collaborator,[13] feeling he needed "a collaborator who was musically and intellectually in a similar place to where I was".[19] They hired Ezrin at the suggestion of Waters's then-girlfriend Carolyne Christie, who had worked as Ezrin's secretary.[15] Ezrin had worked with Alice Cooper, Lou Reed, Kiss, and Peter Gabriel.[20] From the start, Waters made it clear who was in charge, telling him: "You can write anything you want. Just don't expect any credit."[21]

Ezrin and Gilmour reviewed Waters's concept, discarding what they thought was not good enough. Waters and Ezrin worked mostly on the story, improving the concept.[22] Ezrin presented a 40-page script to the rest of the band, with positive results. He recalled: "The next day at the studio, we had a table read, like you would with a play, but with the whole of the band, and their eyes all twinkled, because then they could see the album."[19] Ezrin broadened the storyline, distancing it from the autobiographical work Waters had written and basing it on a composite character named Pink.[23] Engineer Nick Griffiths later said: "Ezrin was very good in The Wall, because he did manage to pull the whole thing together. He's a very forceful guy. There was a lot of argument about how it should sound between Roger and Dave, and he bridged the gap between them."[24] Waters wrote most of the album, with Gilmour co-writing "Comfortably Numb", "Run Like Hell", and "Young Lust",[25] and Ezrin co-writing "The Trial".[22]

Concept and storyline[edit]

The Wall is a rock opera[26] that explores abandonment and isolation, symbolized by a wall. The songs create an approximate storyline of events in the life of the protagonist, Pink, a character based on Syd Barrett[27] as well as Roger Waters,[28] whose father was killed during WWII. Pink's father also dies in a war, which is where Pink starts to build a metaphorical wall around himself. The album includes several references to former band member Syd Barrett, including "Nobody Home", which hints at his condition during Pink Floyd's abortive US tour of 1967, with lyrics such as "wild, staring eyes", "the obligatory Hendrix perm" and "elastic bands keeping my shoes on". "Comfortably Numb" was inspired by Waters' injection with a muscle relaxant to combat the effects of hepatitis during the In the Flesh Tour, while in Philadelphia.[29]

Plot[edit]

Pink is a rock star, one of the many reasons which have left him depressed. Pink imagines a crowd of fans entering one of his concerts, and we begin a flashback on his life, and it is revealed that his father was killed defending the Anzio bridgehead during World War II, in Pink's infancy ("In the Flesh?"). Pink's mother raises him alone ("The Thin Ice"), and with the death of his father, Pink starts to build a metaphorical wall around himself ("Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1").

Growing older, Pink is tormented at school by tyrannical, abusive teachers ("The Happiest Days of Our Lives"), and memories of these traumas become metaphorical "bricks in the wall" ("Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2"). As an adult now, Pink remembers his oppressive and overprotective mother ("Mother") and his upbringing during the Blitz ("Goodbye Blue Sky"). Pink soon marries, and is about to complete his "wall" ("Empty Spaces"). While touring in America, he turns to a willing groupie ("Young Lust"). After learning of his wife's infidelity, he brings the groupie back to his hotel room, only to trash it in a violent fit of rage, terrifying the groupie out of the room ("One of My Turns"). Pink, depressed, thinks about his wife, and feels trapped in his room ("Don't Leave Me Now"), and dismisses every traumatic experience he has ever had as a "brick" in the metaphorical wall ("Another Brick in the Wall, Part 3"), Pink's wall is now finished, completing his total isolation from human contact ("Goodbye Cruel World").

Immediately after the wall's completion, Pink questions his decisions, ("Hey You"), and locks himself in his hotel room ("Is There Anybody Out There?"). Beginning to feel depressed, Pink turns to his possessions for comfort ("Nobody Home"), and yearns for the idea of reconnecting with his personal roots ("Vera"), Pink's mind flashes back to World War II, with the people demanding that the soldiers return home ("Bring the Boys Back Home"). Returning to the present, Pink's manager and roadies have busted into his hotel room, where they find him drugged and unresponsive. A paramedic injects him with drugs to enable him to perform ("Comfortably Numb").

This results in a hallucinatory on-stage performance ("The Show Must Go On") where he believes that he is a fascist dictator, and that his concert is a Neo-Nazi rally, at which he sets brownshirt-like men on fans he considers unworthy ("In the Flesh"). He proceeds to attack ethnic minorities ("Run Like Hell"), and then holds a rally in suburban London, symbolizing his descent into insanity ("Waiting for the Worms"). Pink's hallucination then ceases, and he begs for everything to stop ("Stop"). Showing human emotion, he is tormented with guilt and places himself on trial ("The Trial"), his inner judge ordering him to "tear down the wall", opening Pink to the outside world ("Outside the Wall"). The album turns full circle with its closing words "Isn't this where ...", the first words of the phrase that begins the album, "... we came in?", with a continuation of the melody of the last song hinting at the cyclical nature of Waters' theme.[30]

Production[edit]

Recording[edit]

The album was recorded in several locations. In France, Super Bear Studios was used between January and July 1979, with Waters recording his vocals at the nearby Studio Miraval. Michael Kamen supervised the orchestral arrangements at CBS Studios in New York, in September.[31] Over the next two months the band used Cherokee Studios, Producers Workshop and The Village Recorder in Los Angeles. A plan to work with the Beach Boys at the Sundance Productions studio in Los Angeles was cancelled.[32][33]

James Guthrie, recommended by previous Floyd collaborator Alan Parsons, arrived early in the production process.[34] He replaced engineer Brian Humphries, emotionally drained by his five years with the band.[35] Guthrie was hired as a co-producer, but was initially unaware of Ezrin's role: "I saw myself as a hot young producer ... When we arrived, I think we both felt we'd been booked to do the same job."[36] The early sessions at Britannia Row were emotionally charged, as Ezrin, Guthrie and Waters each had strong ideas about the direction the album would take. Relations within the band were at a low ebb, and Ezrin's became an intermediary between Waters and the rest of the band.[37]

As Britannia Row was initially regarded as inadequate for The Wall, the band upgraded much of its equipment,[38] and by March another set of demos were complete. However, their former relationship with NWG placed them at risk of bankruptcy, and they were advised to leave the UK by no later than 6 April 1979, for a minimum of one year. As non-residents they would pay no UK taxes during that time, and within a month all four members and their families had left. Waters moved to Switzerland, Mason to France, and Gilmour and Wright to the Greek Islands. Some equipment from Britannia Row was relocated in Super Bear Studios near Nice.[24][39] Gilmour and Wright were each familiar with the studio and enjoyed its atmosphere, having recorded solo albums there. While Wright and Mason lived at the studio, Waters and Gilmour stayed in nearby houses. Mason later moved into Waters's villa near Vence, while Ezrin stayed in Nice.[40]

Ezrin's poor punctuality caused problems with the tight schedule dictated by Waters.[41] Mason found Ezrin's behaviour "erratic", but used his elaborate and unlikely excuses for his lateness as ammunition for "tongue-in-cheek resentment".[40] Ezrin's share of the royalties was less than the rest of the band and he viewed Waters as a bully, especially when Waters mocked him by having badges made that read NOPE (No Points Ezrin), alluding to his lesser share.[41] Ezrin later said he had had marital problems and was not "in the best shape emotionally".[41]

More problems became apparent when Waters's relationship with Wright broke down. The band were rarely in the studio together. Ezrin and Guthrie spliced Mason's previously recorded drum tracks together, and Guthrie worked with Waters and Gilmour during the day, returning at night to record Wright's contributions. Wright, worried about the effect that the introduction of Ezrin would have on band relationships, was keen to have a producer's credit on the album; their prior albums had always stated credited production to "Pink Floyd".[42] Waters agreed to a trial period with Wright producing, after which he was to be given a producer's credit, but after a few weeks he and Ezrin expressed dissatisfaction with Wright's methods. A confrontation with Ezrin led to Wright working only at nights. Gilmour also expressed his annoyance, complaining that Wright's lack of input was "driving us all mad".[43] Ezrin later reflected: "it sometimes felt that Roger was setting him up to fail. Rick gets performance anxiety. You have to leave him alone to freeform, to create ..."[43]

Wright was troubled by a failing marriage and the onset of depression, exacerbated by his non-residency. While the other band members brought their children, Wright's were older and could not join as they were attending school; he said he missed them "terribly".[44] The band's holidays were booked for August, after which they were to reconvene at Cherokee Studios in Los Angeles, but Columbia offered the band a better deal in exchange for a Christmas release of the album. Waters increased the band's workload accordingly, booking time at the nearby Studio Miraval.[45] He also suggested recording in Los Angeles ten days earlier than agreed, and hiring another keyboardist to work alongside Wright, whose keyboard parts had not yet been recorded. Wright, however, refused to cut short his family holiday in Rhodes.[46]

Accounts of Wright's subsequent departure from the band differ. In his autobiography, Inside Out, Mason says that Waters called O'Rourke, who was travelling to the US on the QE2, and told him to have Wright out of the band by the time Waters arrived in LA to mix the album.[47] In another version recorded by a later historian of the band, Waters called O'Rourke and asked him to tell Wright about the new recording arrangements, to which Wright responded: "Tell Roger to fuck off".[48] Wright denied this, stating that the band had agreed to record only through the spring and early summer, and that he had no idea they were so far behind schedule. Mason later wrote that Waters was "stunned and furious",[45] and felt that Wright was not doing enough.[45] Gilmour was on holiday in Dublin when he learnt of Waters's ultimatum, and tried to calm the situation. He later spoke with Wright and gave him his support, but reminded him about his minimal contributions.[49] Waters, however, insisted that Wright leave, or he would refuse to release The Wall. Several days later, worried about their financial situation and the failing interpersonal relationships within the band, Wright quit. News of his departure was kept from the music press.[50] Although his name did not appear on the album,[51][52] he was employed as a session musician on the band's subsequent tour.[53]

By August 1979, the running order was largely complete. Wright completed his duties at Cherokee Studios aided by session musicians Peter Wood and Fred Mandel, and Jeff Porcaro played drums in Mason's stead on "Mother".[52] Mason left the final mix to Waters, Gilmour, Ezrin and Guthrie, and travelled to New York to record his debut solo album, Nick Mason's Fictitious Sports.[54] In advance of its release, technical constraints led to some changes to the running order and content of The Wall, with "What Shall We Do Now?" replaced by the similar but shorter "Empty Spaces", and "Hey You" being moved from the end of side three to the beginning. With the November 1979 deadline approaching, the band left the inner sleeves of the album unchanged.[55]

Instrumentation[edit]

Mason's early drum sessions were performed in an open space on the top floor of Britannia Row Studios. The 16-track recordings from these sessions were mixed down and copied onto a 24-track master, as guide tracks for the rest of the band to play to. This gave the engineers greater flexibility,[nb 2] but also improved the audio quality of the mix, as the original 16-track drum recordings were synced to the 24-track master and the duplicated guide tracks removed.[57] Ezrin later related the band's alarm at this method of working – they apparently viewed the erasure of material from the 24-track master as "witchcraft".[37]

While at Super Bear studios, Waters agreed to Ezrin's suggestion that several tracks, including "Nobody Home", "The Trial" and "Comfortably Numb", should have an orchestral accompaniment. Michael Kamen, who had previously worked with David Bowie, was booked to oversee these arrangements, which were performed by musicians from the New York Philharmonic and New York Symphony Orchestras, and a choir from the New York City Opera.[58] Their sessions were recorded at CBS Studios in New York without Pink Floyd present. Kamen eventually met the band once recording was complete.[59]

David Gilmour[60]

"Comfortably Numb" has its origins in Gilmour's debut solo album, and was the source of much argument between Waters and Gilmour.[24] Ezrin claimed that the song initially started life as "Roger's record, about Roger, for Roger", but he thought that it needed further work. Waters changed the key of the verse and added more lyrics to the chorus, and Gilmour added extra bars for the line "I have become comfortably numb". Wright's "stripped-down and harder" recording was not to Gilmour's liking; Gilmour preferred Ezrin's "grander Technicolor, orchestral version", although Ezrin preferred Waters's version. Following a major argument in a North Hollywood restaurant, the two compromised; the song's body included the orchestral arrangement, with Gilmour's second and final guitar solo standing alone.[60]

Sound design[edit]

Ezrin and Waters oversaw the capture of the album's sound effects. Waters recorded the phone call used on the original demo for "Young Lust", but neglected to inform its recipient, Mason, who assumed it was a prank call and angrily hung up.[61] A real telephone operator was also an unwitting participant.[62] The call references Waters' viewpoint of his bitter 1975 divorce from first wife Judy.[63] Waters also recorded ambient sounds along Hollywood Boulevard by hanging a microphone from a studio window. Engineer Phil Taylor recorded some of the screeching tyre noises on "Run Like Hell" from a studio car park, and a television set being destroyed was used on "One of My Turns". At Britannia Row Studios, Nick Griffiths recorded the smashing of crockery for the same song.[64] Television broadcasts were used, and one actor, recognising his voice, accepted a financial settlement from the group in lieu of legal action against them.[65]

The maniacal schoolmaster was voiced by Waters, and actress Trudy Young supplied the groupie's voice.[64] Backing vocals were performed by a range of artists, although a planned appearance by the Beach Boys on "The Show Must Go On" and "Waiting for the Worms" was cancelled by Waters, who instead settled for Beach Boy Bruce Johnston and Toni Tennille.[66]

Ezrin's suggestion to release "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" as a single with a disco-style beat did not initially find favour with Gilmour, although Mason and Waters were more enthusiastic. Waters opposed releasing a single, but became receptive once he listened to Ezrin and Guthrie's mix. With two identical verses the song was felt to be lacking, and so a copy was sent to Griffiths in London with a request to find children to perform several versions of the lyrics.[58] Griffiths contacted Alun Renshaw, head of music at the nearby Islington Green school, who was enthusiastic, saying: "I wanted to make music relevant to the kids – not just sitting around listening to Tchaikovsky. I thought the lyrics were great – 'We don't need no education, we don't need no thought control ...' I just thought it would be a wonderful experience for the kids."[67]

Griffiths first recorded small groups of pupils and then invited more, telling them to affect a Cockney accent and shout rather than sing. He multitracked the voices, making the groups sound larger, before sending his recordings back to Los Angeles. The result delighted Waters, and the song was released as a single, becoming a Christmas number one.[68] There was some controversy when the British press reported that the children had not been paid for their efforts; they were eventually given copies of the album, and the school received a £1,000 donation (£4,000 in contemporary value[16]).[69]

Artwork and packaging[edit]

The album's cover art is one of Pink Floyd's most minimal – a white brick wall and no text. Waters had a falling out with Hipgnosis designer Storm Thorgerson a few years earlier when Thorgerson had included the cover of Animals in his book The Work Of Hipgnosis: 'Walk Away René'. The Wall is therefore the first album cover of the band since The Piper at the Gates of Dawn not to be created by the design group.[70] Issues of the album would include the lettering of the artist name and album title by cartoonist Gerald Scarfe, either as a sticker on sleeve wrapping or printed onto the cover itself, in either black or red. Scarfe, who had previously created animations for the band's "In the Flesh" tour, also created the LP's inside sleeve art and labels of both vinyl records of the album, showing the eponymous wall in various stages of construction, accompanied by characters from the story. The drawings would be translated into dolls for The Wall Tour, as well as into Scarfe's animated segments shown during the tour and the film based on the album.[71][72]

Release and reception[edit]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The Daily Telegraph | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| The Great Rock Discography | 9/10[75] |

| MusicHound Rock | |

| Music Story | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Smash Hits | 8/10[78] |

| Sputnikmusic | 5/5[79] |

| The Village Voice | B–[80] |

When the completed album was played for an assembled group of executives at Columbia's headquarters in California, several were reportedly unimpressed by what they heard.[81] Matters had not been helped when Columbia Records offered Waters smaller publishing rights on the grounds that The Wall was a double album, a position he did not accept. When one executive offered to settle the dispute with a coin toss, Waters asked why he should gamble on something he owned. He eventually prevailed.[54] The record company's concerns were alleviated when "Another Brick in the Wall Part 2" reached number one in the UK, US, Norway, Portugal, West Germany and South Africa.[81] It was certified platinum in the UK in December 1979, and platinum in the US three months later.[82]

The Wall was released in the UK and in the US on 30 November 1979.[nb 3] Coinciding with its release, Waters was interviewed by veteran DJ Tommy Vance, who played the album in its entirety on BBC Radio 1.[70] Critical opinion of its content was mixed.[83] Reviewing for Rolling Stone in February 1980, Kurt Loder hailed it as "a stunning synthesis of Waters's by now familiar thematic obsessions" that "leaps to life with a relentless lyrical rage that's clearly genuine and, in its painstaking particularity, ultimately horrifying."[84] By contrast, The Village Voice critic Robert Christgau regarded it as "a dumb tribulations-of-a-rock-star epic" backed by "kitschy minimal maximalism with sound effects and speech fragments",[85] adding in The New York Times that its worldview is "self-indulgent" and "presents the self-pity of its rich, famous and decidedly postadolescent protagonist as a species of heroism".[86] Melody Maker declared, "I'm not sure whether it's brilliant or terrible, but I find it utterly compelling."[87]

Nevertheless, the album topped the Billboard charts for 15 weeks,[88] selling over a million copies in its first two months of sales[83] and in 1999 was certified 23x platinum.[nb 4][89] It remains one of the best-selling albums of all time in the US,[82][89] between 1979 and 1990 selling over 19 million copies worldwide.[90] The Wall is Pink Floyd's second best selling album after 1973's The Dark Side of the Moon. Engineer James Guthrie's efforts were rewarded in 1980 with a Grammy award for Best Engineered Recording (non-classical).[91] Rolling Stone placed it at number 87 on its 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list in 2003,[92] maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list.[93] Based on such rankings, the aggregate website Acclaimed Music lists The Wall as the 152nd most acclaimed album in history.[94]

Reissues[edit]

A 1994 digitally remastered CD version manufactured in China omits "Young Lust", but retains a composition credit for Waters/Gilmour in the booklet.[95] The album was reissued in three versions as part of the Why Pink Floyd...? campaign, which featured a massive restoration of the band's catalogue with remasterings by producer James Guthrie: in 2011, a "Discovery" edition, featuring the remastered version with no extras; and in 2012, both the "Experience" edition, which adds a bonus disc of unreleased material and other supplementary items, and the "Immersion" version, a seven-disc collection that also adds video materials.[96][97] The album was reissued under the Pink Floyd Records label on 26 August 2016 along with The Division Bell.

Tour[edit]

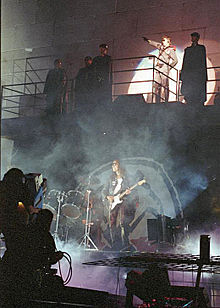

The Wall Tour opened at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena on 7 February 1980. As the band played, a 40-foot (12 m) wall of cardboard bricks was gradually built between them and the audience. Several characters were realised as giant inflatables, including a pig, replete with a crossed hammers logo.[98] Scarfe was employed to produce a series of animations to be projected onto the wall.[98] At his London studio, he employed a team of 40 animators to create nightmarish visions of the future, including a dove of peace, a schoolmaster, and Pink's mother.[99]

For "Comfortably Numb", while Waters sang his opening verse, Gilmour waited in darkness at the top of the wall, standing on a flight case on casters, held steady by a technician, both precariously balanced atop a hydraulic platform. On cue, bright blue and white lights would suddenly illuminate him.[100] At the end of the concert, the wall collapsed, revealing the band.[101] Along with the songs on the album, the tour featured an instrumental medley, "The Last Few Bricks", played before "Goodbye Cruel World" to allow the construction crew to complete the wall.[102]

During the tour, band relationships dropped to an all-time low; four Winnebagos were parked in a circle, with the doors facing away from the centre. Waters used his own vehicle to arrive at the venue, and stayed in separate hotels from the rest of the band. Wright, returning to perform his duties as a salaried musician, was the only member of the band to profit from the tour, which lost about £400,000.[53]

Adaptations[edit]

A film adaptation, Pink Floyd – The Wall, was released in July 1982.[37] It was written by Waters and directed by Alan Parker, with Bob Geldof as Pink. It used Scarfe's animation alongside actors, with little conventional dialogue.[103] A modified soundtrack was created for some of the film's songs.[104]

In 1990, Waters and producer Tony Hollingsworth created The Wall – Live in Berlin, staged for charity at a site once occupied by part of the Berlin Wall.[105] Beginning in 2010[106] and with dates lasting into 2013, Waters performed the album worldwide on his tour, The Wall Live.[107] This had a much wider wall, updated higher quality projected content and leading-edge projection technology. Gilmour and Mason played at one show in London at The O2 Arena.[108] A film of the live concert, Roger Waters: The Wall, was released in 2015.[109] In 2000, Pink Floyd released Is There Anybody Out There? The Wall Live 1980–81, which contains portions of various live shows from the Wall Tour.[110]

In 2016, Waters adapted The Wall into an opera, Another Brick in the Wall: The Opera with contemporary classical composer Julien Bilodeau. It premiered at Opéra de Montréal in March 2017, and was produced by Cincinnati Opera in July 2018.[111] It is orchestrated for a score of eight soloists, 48 chorus members, and a standard 70-piece operatic orchestra.[112]

In 2018, a tribute album The Wall [Redux] was released, with individual artists covering the entire album. This included Melvins' version of "In The Flesh?",[113] Pallbearer covering "Run Like Hell", former Screaming Trees' singer Mark Lanegan covering "Nobody Home" and Church of the Cosmic Skull reworking "The Trial".[114][115]

Track listing[edit]

All tracks written by Roger Waters, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "In the Flesh?" | Waters | 3:16 |

| 2. | "The Thin Ice" |

| 2:27 |

| 3. | "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1" | Waters | 3:11 |

| 4. | "The Happiest Days of Our Lives" | Waters | 1:46 |

| 5. | "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" |

| 3:59 |

| 6. | "Mother" |

| 5:32 |

| Total length: | 20:11 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Goodbye Blue Sky" | Gilmour | 2:45 |

| 2. | "Empty Spaces" | Waters | 2:10 |

| 3. | "Young Lust" (writers: Waters, Gilmour) | Gilmour | 3:25 |

| 4. | "One of My Turns" | Waters | 3:41 |

| 5. | "Don't Leave Me Now" | Waters | 4:08 |

| 6. | "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 3" | Waters | 1:18 |

| 7. | "Goodbye Cruel World" | Waters | 1:16 |

| Total length: | 18:43 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Hey You" | Gilmour, Waters | 4:40 |

| 2. | "Is There Anybody Out There?" | Waters, Gilmour | 2:44 |

| 3. | "Nobody Home" | Waters | 3:26 |

| 4. | "Vera" | Waters | 1:35 |

| 5. | "Bring the Boys Back Home" | Waters | 1:21 |

| 6. | "Comfortably Numb" (writers: Gilmour, Waters) | Gilmour, Waters | 6:23 |

| Total length: | 20:09 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Show Must Go On" | Gilmour | 1:36 |

| 2. | "In the Flesh" | Waters | 4:15 |

| 3. | "Run Like Hell" (writers: Gilmour, Waters) | Waters, Gilmour | 4:20 |

| 4. | "Waiting for the Worms" | Waters, Gilmour | 4:04 |

| 5. | "Stop" | Waters | 0:30 |

| 6. | "The Trial" (writers: Waters, Bob Ezrin) | Waters | 5:13 |

| 7. | "Outside the Wall" | Waters | 1:41 |

| Total length: | 21:39 | ||

Personnel[edit]

Pink Floyd[116]

- Roger Waters – vocals, bass guitar, synthesizer, acoustic guitar on "Mother" and "Vera", electric guitar on "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 3" [117]

- David Gilmour – vocals, electric and acoustic guitars, bass guitar, synthesizer, clavinet, percussion

- Nick Mason – drums, percussion

- Richard Wright – acoustic and electric pianos, Hammond organ, synthesizer, clavinet, bass pedals

Additional musicians

- Bruce Johnston – backing vocals[118]

- Toni Tennille – backing vocals on "In the Flesh?", "The Show Must Go On", "In the Flesh" and "Waiting For The Worms"

- Joe Chemay – backing vocals

- Jon Joyce – backing vocals

- Stan Farber – backing vocals

- Jim Haas – backing vocals

- Bob Ezrin – piano, Hammond organ, synthesizer, reed organ, backing vocals

- James Guthrie – percussion, synthesizer, sound effects

- Jeff Porcaro – drums on "Mother"

- Children of Islington Green School – vocals on "Another Brick in the Wall Part II"

- Joe Porcaro[119] – snare drums on "Bring the Boys Back Home"

- Lee Ritenour – rhythm guitar on "One of My Turns", additional acoustic guitar on "Comfortably Numb"

- Joe (Ron) di Blasi – classical guitar on "Is There Anybody Out There?"

- Fred Mandel – Hammond organ on "In The Flesh?" and "In the Flesh"

- Bobbye Hall – congas and bongos on "Run Like Hell"

- Frank Marocco – concertina on "Outside the Wall"

- Larry Williams – clarinet on "Outside the Wall"

- Trevor Veitch – mandolin on "Outside the Wall"

- New York Orchestra – orchestra

- New York Opera – choral vocals

- Vicki Brown and Clare Torry (credited simply as "Vicki & Clare") – backing vocals on "The Trial"

- Harry Waters – child's voice on "Goodbye Blue Sky"

- Chris Fitzmorris – male telephone voice

- Trudy Young – voice of the groupie

- Phil Taylor – sound effects

Production

- David Gilmour – co-producer

- Roger Waters – co-producer

- Bob Ezrin – production, orchestral arrangement, music on "The Trial"

- Michael Kamen – orchestral arrangement

- James Guthrie – co-producer, engineer

- Nick Griffiths – engineer

- Patrice Quef – engineer

- Brian Christian – engineer

- Rick Hart – engineer

- Doug Sax – mastering

- John McClure - engineer

- Phil Taylor – sound equipment

- Gerald Scarfe – sleeve design

- Roger Waters – sleeve design

- Joel Plante – mastering[118]

Charts and certifications[edit]

Album

| Chart (1979–80) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[120] | 1 |

| Austrian Albums (Ö3 Austria)[121] | 1 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[122] | 1 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[123] | 1 |

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[124] | 1 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[125] | 1 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[126] | 1 |

| Spanish Albums (AFE)[127] | 1 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[128] | 1 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[129] | 3 |

| US Billboard 200[130] | 1 |

| Chart (1990) | Peak position |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[131] | 19 |

| Chart (2005–06) | Peak position |

| Austrian Albums (Ö3 Austria)[132] | 11 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[133] | 85 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Wallonia)[134] | 81 |

| Danish Albums (Hitlisten)[135] | 19 |

| Finnish Albums (Suomen virallinen lista)[136] | 21 |

| Italian Albums (FIMI)[137] | 13 |

| Spanish Albums (PROMUSICAE)[138] | 9 |

| Swiss Albums (Schweizer Hitparade)[139] | 29 |

| Chart (2011–20) | Peak position |

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[140] | 20 |

| Austrian Albums (Ö3 Austria)[141] | 15 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[142] | 44 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Wallonia)[143] | 20 |

| Czech Albums (ČNS IFPI)[144] | 7 |

| Danish Albums (Hitlisten)[145] | 10 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[146] | 15 |

| Finnish Albums (Suomen virallinen lista)[147] | 17 |

| French Albums (SNEP)[148] | 12 |

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[124] | 4 |

| Irish Albums (IRMA)[149] | 38 |

| Italian Albums (FIMI)[150] | 4 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[151] | 14 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[152] | 10 |

| Polish Albums (ZPAV)[153] | 8 |

| Portuguese Albums (AFP)[154] | 10 |

| Spanish Albums (PROMUSICAE)[155] | 15 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[156] | 13 |

| Swiss Albums (Schweizer Hitparade)[157] | 8 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[158] | 22 |

| US Billboard 200[159] | 17 |

Singles

| Date | Single | Chart | Position | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 November 1979 | "Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)" | UK Top 40 | 1 | [nb 5][160] |

| 7 January 1980 | "Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)" | US Billboard Pop Singles | 1 | [nb 6][82] |

| 9 June 1980 | "Run Like Hell" | US Billboard Pop Singles | 53 | [nb 7][82] |

| March 1980 | "Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)" | Norway's single chart | 1 | [161] |

Certifications

| Country | Certification | Sales | Last certification date | Comment | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Platinum | 200,000 | 23 August 1999 | [162] | |

| Australia | 11× Platinum | 770,000 | 2011 | [163] | |

| Brazil | Platinum | 80,000 | [164] | ||

| Canada | 2× Diamond | 2,000,000 | 31 August 1995 | [165] | |

| France | Diamond | 1,576,100 | 1991 | [166] | |

| Germany | 4× Platinum | 2,000,000 | 1994 | [167] | |

| Greece | 100,000 | [168] | |||

| Italy | 4× Platinum | 200,000 | 2019 | sales of Parlophone edition | [169] |

| Italy | 1× Platinum | 50,000 | 2016 | sales of EMI MKTG edition | [170] |

| New Zealand RMNZ | 14× Platinum | 210,000 | 29 January 2011 | [171] | |

| Poland | Platinum | 100,000 | 29 October 2003 | [172][173] | |

| Spain | Platinum | 100,000 | 1980 | [174] | |

| United Kingdom | 2x Platinum | 600,000 | 22 July 2013 | [175] | |

| United States RIAA | 23× Platinum | 11,500,000 | 29 January 1999 | [176] | |

| United States Soundscan | 5,381,000 | 29 August 2008 | Since March 1991 – August 2008 | [177][178] |

References[edit]

Notes

- ^ Pink Floyd eventually sued NWG for £1 million, accusing them of fraud and negligence. NWG collapsed in 1981. Andrew Warburg fled to Spain, Norton Warburg Investments (a part of NWG) was renamed to Waterbrook, and many of its holdings were sold at a loss. Andrew Warburg was jailed for three years upon his return to the UK in 1987.[18]

- ^ As well as being more flexible, repeated replay of magnetic tape can, over time, reduce the quality of the recorded material.

- ^ EMI Harvest SHDW 411 (double album)[82]

- ^ As a double album 23x platinum signifies sales of 11.5 million.

- ^ EMI Harvest HAR 5194 (7" single)

- ^ Columbia 1-11187 (7" single)

- ^ Columbia 1-11265 (7" single)

Footnotes

- ^ Brown, Jake (2011). Jane's Addiction: In the Studio. SCB Distributors. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-9834716-2-2.

- ^ Murphy, Sean (17 November 2015). "The 25 Best Classic Progressive Rock Albums". PopMatters. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Breithaupt, Don; Breithaupt, Jeff (2000), Night Moves: Pop Music in the Late '70s, St. Martin's Press, p. 71, ISBN 978-0-312-19821-3

- ^ Barker, Emily (8 July 2015). "23 Of The Maddest And Most Memorable Concept Albums". NME. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 48. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Turner, Steve: "Roger Waters: The Wall in Berlin"; Radio Times, 25 May 1990; reprinted in Classic Rock #148, August 2010, p76

- ^ Scarfe 2010, p. 51

- ^ Schaffner, p 329

- ^ Schaffner, pp 219–220

- ^ a b Mason 2005, pp. 235–236

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 256–257

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 258

- ^ a b c Blake 2008, p. 259

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 305

- ^ a b Blake 2008, pp. 258–259

- ^ a b UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b Gwyther, Matthew (7 March 1993). "The dark side of success". Observer magazine. p. 37.

- ^ a b Schaffner 1991, pp. 206–208

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 260

- ^ Fitch & Mahon 2006, p. 25

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 212

- ^ a b Schaffner 1991, pp. 211–213

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 260–261

- ^ a b c Schaffner 1991, p. 213

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 278

- ^ "Rock Milestones: Pink Floyd – The Wall", The New York Times, retrieved 30 May 2010; Pink Floyd's Roger Waters Announces The Wall Tour, MTV, retrieved 30 May 2010; Top 14 Greatest Rock Operas/Concept Albums Of All Time, ign.com, retrieved 30 May 2010

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 225–226

- ^ Scarfe 2010, p. 57

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 274

- ^ Fitch & Mahon 2006, pp. 71, 113

- ^ "Pink Floyd news :: Brain Damage - Michael Kamen". Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Fitch & Mahon 2006, pp. 50–59, 71–113

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 232

- ^ Fitch & Mahon 2006, p. 26

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 238

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 262

- ^ a b c Blake 2008, p. 263

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 240

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 262–263

- ^ a b Mason 2005, pp. 243–244

- ^ a b c Blake 2008, p. 264

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 265

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 266

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Blakep2672was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Mason 2005, p. 245

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 264–267

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 246

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 267

- ^ Simmons 1999, p. 88

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 267–268

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 219

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 269

- ^ a b Blake 2008, pp. 285–286

- ^ a b Mason 2005, p. 249

- ^ Bench & O'Brien 2004, pp. 70–72

- ^ McCormick, Neil (31 August 2006), "Everyone wants to be an axeman...", The Daily Telegraph, retrieved 28 September 2009

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 239–242

- ^ a b Blake 2008, pp. 271–272

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 247

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 275

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 237

- ^ Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd - The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 189

- ^ a b Blake 2008, pp. 269–271

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 250

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 214

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 273

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 273–274

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 215–216

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 279

- ^ Simmons 1999, pp. 76–95

- ^ "Interview: Gerald Scarfe". Floydian Slip. 5–7 November 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Album review at AllMusic. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (20 May 2014). "Pink Floyd's 14 studio albums rated". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ a b c "Pink Floyd The Wall". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (eds) (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 872. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (2 November 2004). "Pink Floyd: Album Guide". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media, Fireside Books. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Starr, Red. "Albums". Smash Hits (December 13–26, 1979): 29.

- ^ Med57. "The Wall". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (31 March 1980). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved 13 June 2020 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ a b Blake 2008, pp. 275–276

- ^ a b c d e Povey 2007, p. 348

- ^ a b Blake 2008.

- ^ Loder, Kurt (7 February 1980), "Pink Floyd — The Wall", Rolling Stone, archived from the original on 3 May 2008, retrieved 6 October 2009

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: P". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved 10 March 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (15 December 1984). "Censorship Is Not a Cure for Teen-Age Suicide". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2020 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 277

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 221

- ^ a b GOLD & PLATINUM, riaa.com, archived from the original on 1 July 2007, retrieved 10 January 2011

- ^ Holden, Stephen (25 April 1990), "Putting Up 'The Wall'", The New York Times, retrieved 21 August 2009

- ^ Grammy Award Winners (search for The Wall), National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, archived from the original on 2 October 2009, retrieved 7 October 2009

- ^ "The Wall – Pink Floyd", Rolling Stone, retrieved 30 March 2011

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ "Pink Floyd". Acclaimed Music. Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ EMI/Harvest 00946 368220 2 0 copyright owned by Pink Floyd Music Ltd.

- ^ "Why Pink Floyd...? Official website". EMI. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ Topping, Alexandra (10 May 2011). "Pink Floyd to release unheard tracks". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ a b Blake 2008, pp. 280–282

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 223–225

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 284–285

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 252

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 233The band also played "What Shall We Do Now?", which was kept off the original album due to time constraints.

- ^ Romero, Jorge Sacido. "Roger Waters' Poetry of the Absent Father: British Identity in Pink Floyd's "The Wall"" Atlantis 28.2 (2006): 45–58. JSTOR. Web. 21 Feb. 2015.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 288–292

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 342–347

- ^ "Roger Waters Pictures Madison Square Garden 11-06-2010". ClickitTicket.

- ^ "Roger Waters to Restage 'The Wall' on 2010 Tour". CBS News. CBS News. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Greene, Andy (12 May 2011). "Pink Floyd Reunite at Roger Waters Show in London". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Roger Waters: The Wall review – primo stadium spectacle meets History Channel doc". The Guardian. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 354

- ^ "Cincinnati Opera to give U.S. premiere of 'Another Brick in the Wall' with music by Pink Floyd's Roger Waters". Cincinnati Enquirer. 16 March 2017.

- ^ "'The Wall' Opera Gets U.S. Release Date". Entertainment Weekly. 13 March 2017.

- ^ "Hear Melvins Out-Strange Pink Floyd With Sludgy "In the Flesh?" Cover". Revolver. 1 November 2018.

- ^ "Pallbearer's cover of Pink Floyd's "Run Like Hell" might be better than the original". Revolver Magazine. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ "Another Brick from The Wall (Redux) - Mark Lanegan 'Nobody Home'". Noise11. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ "Pink Floyd - The Wall". Discogs. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Fitch, Vernon (2005). 'The Pink Floyd Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). pp. 73, 76, 88. ISBN 1-894959-24-8.

- ^ a b "The Wall – Pink Floyd | Credits | AllMusic". AllMusic.

- ^ "Blue Ocean Drummer and Percussionist New York City". bleu-ocean.com.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (Illustrated ed.). St. Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 233. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 9481a". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Offiziellecharts.de – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "New Zealand charts portal (23/12/1979)". charts.nz. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Norwegian charts portal (50/1979)". norwegiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos:año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Swedish charts portal (14/12/1979)". swedishcharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Pink Floyd – The Wall". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd: The Wall" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Wall". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Spanishcharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Wall". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Wall". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Wall". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Czech Albums – Top 100". ČNS IFPI. Note: On the chart page, select 201209 on the field besides the word "Zobrazit", and then click over the word to retrieve the correct chart data. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Danish charts portal (09/03/2012)". danishcharts.dk. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Finnish charts portal (10/2012)". finnishcharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Les charts francais (03/03/2012)". lescharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "GFK Chart-Track Albums: Week 9, 2012". Chart-Track. IRMA. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Italian charts portal (08/03/2012)". italiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "New Zealand charts portal (05/03/2012)". charts.nz. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Norwegian charts portal (10/2012)". norwegiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Portuguese charts portal (10/2012)". portuguesecharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Spanish charts portal (04/03/2012)". spanishcharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Swedish charts portal (02/03/2012)". swedishcharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Wall". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 347

- ^ Pink Floyd – Another Brick In The Wall (Part II), norwegiancharts.com, retrieved 3 July 2009

- ^ Gold & Platin, capif, archived from the original on 31 May 2011, retrieved 5 July 2009

- ^ Platinum, archived from the original on 29 September 2014, retrieved 21 July 2011

- ^ Pró-Música Brasil, pro-musicabr.org.br, retrieved 23 February 2019

- ^ Canadian certification database, cria.ca, archived from the original on 1 May 2010, retrieved 31 March 2018

- ^ "Les Meilleures Ventes de CD / Albums "Tout Temps"" (in French). InfoDisc. Syndicat National de l'Edition Phonographique. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Pink Floyd; 'The Wall')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Ewbank, Alison J; Papageorgiou, Fouli T (1997), Whose master's voice? Door Alison J. Ewbank, Fouli T. Papageorgiou, page 78, Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-27772-6, retrieved 9 July 2009

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 14 October 2019. Select "2019" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Select "The Wall" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 23 February 2019. Select "2011" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Select "The Wall" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ NZ Top 40 Album Chart, nztop40.co.nz, retrieved 13 July 2017

- ^ "Polish album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Wall" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. 29 October 2003.

- ^ "ZASADY PRZYZNAWANIA ZŁOTYCH, PLATYNOWYCH I DIAMENTOWYCH PŁYT", zpav.pl (in Polish), ZPAV, 27 November 2001, archived from the original on 20 February 2004

- ^ Sólo Éxitos 1959–2002 Año A Año: Certificados 1979–1990 (in Spanish), Iberautor Promociones Culturales, ISBN 8480486392, retrieved 21 August 2013

- ^ Certified Awards, bpi.co.uk, archived from the original on 24 January 2013, retrieved 28 September 2013

- ^ Gold & Platinum - RIAA, riaa.com, retrieved 16 March 2019

- ^ Get Your Mind Right: Underground Vs. Mainstream, Cheri Media Group, archived from the original on 11 March 2011, retrieved 12 February 2013

- ^ Chart Watch Extra: Vintage Albums That Just Keep On Selling, Paul Grein, retrieved 9 July 2009

Bibliography

- Blake, Mark (2008), Comfortably Numb – The Inside Story of Pink Floyd (1st US paperback ed.), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-81752-6

- Fitch, Vernon; Mahon, Richard (2006), Comfortably Numb: A History of "The Wall": Pink Floyd 1978–1981 (1st US hardcover ed.), St. Petersburg, Florida: PFA Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9777366-0-7

- Mason, Nick (2005), Philip Dodd (ed.), Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (UK paperback ed.), London: Phoenix, ISBN 978-0-7538-1906-7

- Povey, Glenn (2007), Echoes (1st UK paperback ed.), London: Mind Head Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5

- Bench, Jeff; O'Brien, Daniel (2004), Pink Floyd's The Wall: In the Studio, On Stage and On Screen (UK paperback ed.), London: Reynolds and Hearn, ISBN 978-1-903111-82-6

- Scarfe, Gerald (2010), The Making of Pink Floyd: The Wall (1st US paperback ed.), New York: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-81997-1

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1991), Saucerful of Secrets (UK paperback ed.), London: Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN 978-0-283-06127-1

- Simmons, Sylvie (December 1999), "Pink Floyd: The Making of The Wall", Mojo, London: Emap Metro, 73: 76–95

Further reading

- Di Perna, Alan (2002), Guitar World Presents Pink Floyd, Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, ISBN 978-0-634-03286-8

- Fitch, Vernon (2001), Pink Floyd: The Press Reports 1966–1983, Ontario: Collector's Guide Publishing Inc, ISBN 978-1-896522-72-2

- Fricke, David (December 2009), "Roger Waters: Welcome to My Nightmare ... Behind The Wall", Mojo, London: Emap Metro, 193: 68–84

- Hiatt, Brian (September 2010), "Back to The Wall", Rolling Stone, 1114: 50–57CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacDonald, Bruno (1997), Pink Floyd: through the eyes of ... the band, its fans, friends, and foes, New York: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-80780-0

- Mabbett, Andy (2010), Pink Floyd The Music and the Mystery, London: Omnibus Press, ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Wall |

- The Wall (rock opera)

- 1979 albums

- Albums produced by Roger Waters

- Albums produced by James Guthrie (record producer)

- Albums produced by Bob Ezrin

- Albums produced by David Gilmour

- Capitol Records albums

- Columbia Records albums

- Concept albums

- EMI Records albums

- Harvest Records albums

- Pink Floyd albums

- Art rock albums by English artists

- Rock operas

- Mental illness in fiction

- Fiction with unreliable narrators

- Albums recorded at CBS 30th Street Studio

- Progressive pop albums

- Albums recorded at Studio Miraval

- Juno Award for International Album of the Year albums