Sennacherib

| Sennacherib | |

|---|---|

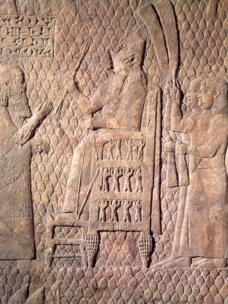

Cast of a rock relief of Sennacherib from the foot of Mount Judi, near Cizre. | |

| King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 705–681 BC |

| Predecessor | Sargon II |

| Successor | Esarhaddon |

| Born | c. 745 BC[1] Kalhu[2] (?) |

| Died | 20 October 681 BC (aged c. 64) Nineveh |

| Spouse | Tashmetu-sharrat Naqi'a |

| Issue Among others | Ashur-nadin-shumi Arda-Mulissu Esarhaddon |

| Akkadian | Sîn-ahhī-erība Sîn-aḥḥē-erība |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Sargon II |

| Mother | Ra'īmâ (?) |

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

Sennacherib (Akkadian: Sîn-ahhī-erība[3] or Sîn-aḥḥē-erība,[4] meaning "Sîn has replaced the brothers"[5]) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705 BC to his own death in 681 BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is among the most famous of all Assyrian kings due to the role he played in the Old Testament of the Bible, which describes his campaign in the Levant.[6] Other events of his reign which secured his legacy throughout the millennia following his death include his destruction of the city Babylon in 689 BC and his construction of the last great Assyrian capital, Nineveh.

Although Sennacherib was one of the most powerful and wide-ranging of all the Assyrian kings,[7] he faced considerable difficulty in controlling Babylonia, which formed the southern portion of his empire. Many of Sennacherib's Babylonian troubles stemmed from the Chaldean tribal chief Marduk-apla-iddina II, who had been Babylon's king until he was defeated by Sennacherib's father. Shortly after Sennacherib inherited the throne in 705 BC, Marduk-apla-iddina retook Babylon and allied with the Elamites. Though Sennacherib reclaimed the south in 700 BC, Marduk-apla-iddina continued to trouble him, probably instigating Assyrian vassals in the Levant to rebel and successfully convincing Sennacherib's vassal king in Babylonia, Bel-ibni, to also throw off Sennacherib's rule. After the Babylonians and Elamites captured and executed Sennacherib's eldest son Ashur-nadin-shumi, whom Sennacherib had proclaimed as his vassal king in Babylon, Sennacherib campaigned in both regions, successfully subduing Elam. Because Babylon, well within his own territory, had been the target of most of his military campaigns and had caused the death of his son, Sennacherib destroyed the city in 689 BC.

The Levantine War of 701 BC was made necessary because several Assyrian vassals in the region decided to rebel, either because they were encouraged by Marduk-apla-iddina or because of the ill omens associated with the battlefield death of Sennacherib's father. Though the northern Levant was subdued relatively quickly, the states in the southern Levant, especially the Kingdom of Judah under King Hezekiah, did not submit as easily. The Assyrians thus invaded Judaea, a campaign which is recorded not only in Sennacherib's own accounts but also in the Second Book of Kings in the Hebrew Bible. Though the biblical narrative holds that Sennacherib's attack on Jerusalem was defeated through divine intervention by an angel destroying the Assyrian army, an outright Assyrian defeat is unlikely as Hezekiah submitted to Sennacherib at the end of the campaign.

Sennacherib transferred the capital of Assyria to Nineveh, where he had spent most of his time as crown prince. In order to transform Nineveh into a capital worthy of his empire, he launched one of the most ambitious building projects in ancient history. He expanded the size of the city, constructed great city walls, numerous temples and a great royal garden. His most famous work in the city is the Southwest Palace, a large palace which Sennacherib himself called the "Palace without Rival".

After his eldest son and crown prince, Ashur-nadin-shumi was killed by the Elamites, Sennacherib originally designated his second eldest son, Arda-Mulissu, as his heir, but later replaced him with a younger son, Esarhaddon, in 684 BC, for unknown reasons. Sennacherib ignored repeated appeals from Arda-Mulissu to be reinstated as heir. Sennacherib was assaulted and murdered by Arda-Mulissu and another son, who hoped to seize power for themselves, in 681 BC. His death was welcomed as divine punishment in Babylonia and the Levant, while the Assyrian heartland probably reacted with resentment and horror. Arda-Mulissu's coronation was postponed, and Esarhaddon raised an army and seized Nineveh, installing himself as king as intended by Sennacherib.

Background[edit]

Ancestry and early life[edit]

Sennacherib was the son and successor of the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II, who had reigned as king of Assyria from 722 to 705 BC and as king of Babylon from 710 to 705 BC. The identity of Sennacherib's mother is not entirely certain. Though the most popular view historically has been that Sennacherib was the son of Sargon's wife Ataliya, this is probably impossible. To be the mother of Sennacherib, Ataliya would have had to be born at the latest around the year 760 BC and lived to about 692 BC, but Ataliya's grave at Kalhu indicates that she was at most 35 years old when she died. It is considered more plausible that Sennacherib's mother was another of Sargon's wives, Ra'īmâ, who in a stele from Assur (once the capital of Assyria) is specifically referred to as the "mother of Sennacherib".[8] Sargon claimed that he was the son of the earlier king Tiglath-Pileser III, but this is uncertain as Sargon usurped the throne from Tiglath-Pileser's (other) son Shalmaneser V.[9]

Sennacherib was probably born c. 745 BC. If Sargon was the son of Tiglath-Pileser and not a non-dynastic usurper, he would probably have lived in the royal palace at Kalhu for several years before becoming king. Sennacherib would then probably have been born at Kalhu, where he would then have grown up and spent most of his youth. Sargon lived in Kalhu until long after becoming king, leaving the city in 710 BC to reside at Babylon and later at his new capital, Dur-Sharrukin. By that point Sennacherib, who served as Sargon's crown prince and intended heir to the throne had already left the city, living in a residence at Nineveh.[2] Nineveh had been the designated seat of the Assyrian crown prince since the reign of Tiglath-Pileser.[10] As crown prince, Sennacherib also owned an estate at Tarbisu. Alongside his siblings, Sennacherib would have been educated by the royal educator Hunnî, probably receiving a scribal education, learning some arithmetic and learning how to read and write in Sumerian and Akkadian.[2]

He had several brothers and at least one sister. In addition to the older brothers who died before his birth, Sennacherib also had younger brothers, some of which are mentioned as being alive as late as 670 BC, then in the service of Sennacherib's son and successor Esarhaddon. Sennacherib's only known sister, Ahat-abisha, was married off to Ambaris, the king of Tabal, but probably returned to Assyria after Sargon's first successful campaign against Tabal.[11]

Sennacherib's name, Sîn-aḥḥē-erība in Akkadian, means "Sîn (the moon-god) has replaced the brothers". The name probably derives from Sennacherib not being Sargon's first son, but all of his older brothers being dead by the time he was born. In Hebrew, his name was rendered as Snḥryb and in Aramaic it was Šnḥ’ryb.[5] As per a 670 BC document, it was illegal to give the name Sennacherib (then the former king) to a commoner in Assyria, as it was considered a taboo and sacrilege.[8]

Sennacherib as crown prince[edit]

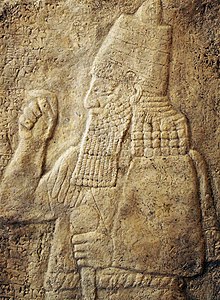

As crown prince, Sennacherib exercised royal power together with his father, or alone as a substitute while Sargon was away campaigning. During Sargon's longer absences from the Assyrian heartland, Sennacherib's residence would have served as the center of government in the Neo-Assyrian Empire, with the crown prince taking on significant administrative and political responsibilities.[10] The vast responsibilities entrusted to Sennacherib suggests a certain degree of trust between the king and the crown prince. In reliefs depicting both Sargon and Sennacherib, they are depicted in discussion, appearing almost as equals. As regent, Sennacherib's main duty was to maintain relations with Assyrian governors and generals and oversee the vast military intelligence network of the empire. Sennacherib also oversaw domestic affairs and often informed Sargon of the progress being made on building projects throughout the empire.[12] Sennacherib was also assigned to the distribution and reception of audience gifts and tribute, after distributing such financial resources, Sennacherib sent letters to his father to inform him of the decisions made.[13]

Sennacherib's letter to his father indicates that he respected him and that they were on friendly terms. He never disobeyed his father and though his letters indicate that he wanted to please Sargon, they also show that he knew him quite well. For unknown reasons Sargon never brought Sennacherib along on his military campaigns, something Sennacherib may have resented his father for as he missed out on the glory attached to military victories.[14] In any event, Sennacherib never took action against Sargon or attempted to usurp the throne despite being more than old enough to become king on his own.[14]

Assyria and Babylonia[edit]

By the time Sennacherib became king, the Neo-Assyrian Empire had been the dominant power in the Near East for more than thirty years, chiefly due to its well-trained and large army which was superior to that of any other contemporary kingdom. Though Babylonia to the south had once been a large kingdom as well, it was typically weaker than its northern neighbor during this period, due to being internally divided and lacking the well-organized army of the Assyrians. The population of Babylonia was divided into various ethnic groups with different priorities and ideas. Though most of the cities, such as Babylon itself and Kish, Ur, Uruk, Borsippa and Nippur, were ruled by the old native Babylonians, most of the southernmost land was dominated by Chaldean tribes led by chieftains who often squabbled with each other.[7] The Arameans lived on the fringes of settled land and were notorious for plundering surrounding territories. Because of the infighting of these three major groups, Babylonia often represented an appealing target for Assyrian campaigns.[15] The two kingdoms had competed since the rise of the Middle Assyrian Empire in the 14th century BC and in the 8th century BC, the Assyrians consistently gained the upper hand.[16] Babylon's internal and external weakness led to its conquest by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III in 729 BC.[15]

During the expansion of Assyria into a major empire, the Assyrians had conquered various neighboring kingdoms, generally either annexing them as Assyrian provinces or turning them into vassal states. However, because the Assyrians venerated the long history and culture of Babylon, it was preserved as a full kingdom, either ruled by an appointed client king, or by the Assyrian king in a personal union.[15] The relationship between Assyria and Babylonia was not entirely unlike the relationship between Greece and Rome in later centuries; Assyria and Babylonia shared the same language and a large amount of Assyria's own culture, texts and traditions had been imported from the south.[17] The relationship between Assyria and Babylon was emotional in a sense, with the implicit gendering of the two countries as the Assyrian metaphorical "husband" to its "wife" Babylon in Neo-Assyrian inscriptions and worldview. In the words of Assyriologist Eckart Frahm, "the Assyrians were in love with Babylon, but also wished to dominate her". Though Babylon was respected as the well-spring of civilization, it was expected to remain passive in political matters, something which Assyria's "Babylonian bride" repeatedly refused to do.[18]

Reign[edit]

Death of Sargon II and succession[edit]

In 705 BC, Sargon, probably in his sixties, led the Assyrian army on a campaign against King Gurdî of Tabal in central Anatolia. The campaign was disastrous, resulting in the defeat of the Assyrian army and the death of Sargon, whose corpse was carried off by the Anatolians.[19][20] The defeat was made significantly worse by the death of Sargon, who Assyrians believed was punished by the gods for some major past misdeed. In Mesopotamian mythology, the afterlife suffered by those who died in battle and weren't buried was terrible, doomed to suffer like beggars for eternity.[21] Sennacherib was about 35 years old when he ascended to the Assyrian throne in August of 705 BC[22] and was well experienced with how to rule the empire due to his long tenure as crown prince.[23] His reaction to the fate of his father was to distance himself from Sargon[24] and appears to have been in denial, refusing to acknowledge and deal with what happened to him. Sargon's great new capital, Dur-Sharrukin, was abandoned immediately and the capital was instead moved to Nineveh. Before he began any other major projects, one of Sennacherib's first actions as king was to rebuild a temple dedicated to the god Nergal, associated with death, disaster and war, at the city Tarbisu.[21]

Even with this public denial in mind, Sennacherib was superstitious and spent much time asking his diviners what kind of sin Sargon could have committed to suffer the fate that he did, possibly considering the idea that Sargon might have offended Babylon's deities by taking control of the city.[25] A text, though probably written after Sennacherib's own death, states that Sennacherib proclaimed he was investigating the nature of a "sin" committed by his father.[26] A minor 704 BC[27] campaign (unmentioned in Sennacherib's later historical accounts), led by Sennacherib's magnates rather than the king himself, was sent against Gurdî in Tabal to avenge Sargon. Sennacherib spent a lot of time and effort to rid the empire of Sargon's imagery. Images which Sargon had created at the temple in Assur were made invisible through raising the level of the courtyard, Sargon's wife Ataliya was buried hastily when she died without regard to the traditional burial practices (and in the same coffin as another woman, the queen of the previous king Tiglath-Pileser), and Sargon is never mentioned in his inscriptions.[28]

First Babylonian campaign[edit]

Sargon II's death in the battle and the disappearance of his body inspired rebellions across the Assyrian Empire.[20] Sargon had ruled Babylonia since 710 BC, when he defeated the Chaldean tribal chief Marduk-apla-iddina II, who had taken control of the south in the aftermath of the death of Sargon's predecessor Shalmaneser V in 722 BC.[29] As with his immediate predecessors, Sennacherib took the ruling titles of both Assyria and Babylonia when he became king, but his reign in Babylonia was less stable.[25] Unlike Sargon and previous Babylonian rulers, who had proclaimed themselves as shakkanakku (viceroys) of Babylon, in reverence for the city's deity Marduk (who was considered Babylon's formal "king"), Sennacherib explicitly proclaimed himself as Babylon's king. Furthermore, Sennacherib did not "take the hand" of the Statue of Marduk, the physical representation of the deity, and thus did not honor the god by undergoing the traditional Babylonian coronation ritual.[30]

Angered by the disrespect, revolts a month apart in 704[29] or 703[25][31] BC overthrew Sennacherib's rule in the south. First, a Babylonian by the name of Marduk-zakir-shumi II took the throne, but was deposed after just two[25] or four[29][31] weeks by Marduk-apla-iddina, the same Chaldean warlord who had seized control of the city once before and had warred against Sennacherib's father. Marduk-apla-iddina's main strength was his ability to unite the normally infighting Chaldean tribes and the Babylonians against the Assyrians.[25] Shutur-Nahhunte II, the king of Elam (a civilization in modern-day south-western Iran), sent aid to Marduk-apla-iddina, sending an army of 80,000 Elamite bowmen, supported by cavalry, under the command of his commander. Elam's massive support inspired the rest of the Chaldean tribes and the Arameans to join the ranks of the Babylonian king.[31]

Due to portions of the Assyrian army being absent in Tabal in 704 BC and Sennacherib possibly considering a two-front war too risky, he left Marduk-apla-iddina unchallenged for several months. After the Tabal expedition had been completed, Sennacherib gathered the Assyrian army at Assur in 703 BC, often used as a mustering spot for campaigns against the south.[27] The Assyrian army, led by Sennacherib's chief commander, launched an unsuccessful attack on the coalition forces near the city of Kish,[31] bolstering the legitimacy of the coalition.[32] Once Sennacherib, encamped by the city of Kutha, received word of the defeat of his first army he personally led the next attack, defeating the coalition troops near Kish. At this point, the anti-Assyrian army was led by Elam as Marduk-apla-iddina, fearing for his life, had fled to the southern Sea Land (the marshlands in southernmost Mesopotamia). Among the captives taken after the victory was a stepson of Marduk-apla-iddina and brother of an Arabian queen, Yatie, who had joined the coalition.[31]

Sennacherib then marched directly towards Babylon. As the Assyrians appeared on the horizon, Babylon opened its gates to Sennacherib, surrendering without a fight.[32] The Assyrians then spent five days unsuccessfully hunting for Marduk-apla-iddina in the Sea Land, destroying the fields of Chaldeans, Arameans and Babylonians who had supported the revolting regime and taking more than two hundred thousand prisoners.[31] The city of Babylon itself was also reprimanded, suffering a minor sack,[32] though the citizens were not harmed.[33] Because his previous policy of reigning as king of both Assyria and Babylonia had evidently failed, Sennacherib attempted another method, appointing a native Babylonian who had grown up at the Assyrian court, Bel-ibni, as his vassal king of the south. Bel-ibni was described by Sennacherib as "a native of Babylon who grew up in my palace like a young puppy".[25]

War in the Levant[edit]

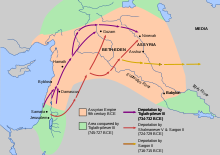

After the Babylonian war, Sennacherib's second campaign was in the Zagros Mountains. There, Sennacherib subdued the Yasubigallians, a people from east of the Tigris river,[34] and the Kassites, a people which centuries prior had ruled Babylonia.[35] Sennacherib's third campaign, directed against the kingdoms and city-states in the Levant, is very well documented compared to many other events in the ancient Near East. Notably, it is the most well-documented event in the history of Israel during the First Temple period.[4] In 705 BC, Hezekiah, the king of Judah, had stopped paying his annual tribute to the Assyrians and began pursuing a markedly aggressive foreign policy, probably inspired by the recent wave of anti-Assyrian rebellions across the empire. Hezekiah conspired with Egypt and Sidqia, an anti-Assyrian king of the city Ashkelon, attacked Philistine cities loyal to Assyria and captured the Assyrian vassal Padi, king of Ekron, and imprisoned him in his capital Jerusalem.[20] In the northern Levant, former Assyrian vassal cities rallied around Luli, the king of Tyre and Sidon.[31] The anti-Assyrian sentiment among some of the empire's western vassals was encouraged by Sennacherib's arch-enemy Marduk-apla-iddina, who corresponded with and sent gifts to western rulers such as Hezekiah,[31] probably hoping to assemble a vast anti-Assyrian alliance.[25]

In 701 BC, Sennacherib first moved to attack the Syro-Hittite and Phoenician cities in the north. Like many rulers of these cities had done before and would do after, Luli decided to flee rather than face the wrath of the Assyrians, escaping by boat until he was safely outside of Sennacherib's reach. In his stead, Sennacherib proclaimed a noble by the name Ethbaal as the new king of Sidon as his vassal and oversaw the submission of many of the surrounding cities to his rule. Faced with a massive Assyrian army nearby, many of the Levantine rulers, including Budu-ilu of Ammon, Kamusu-nadbi of Moab, Mitini of Ashdod and Malik-rammu of Edom, quickly submitted to Sennacherib to avoid retribution.[34]

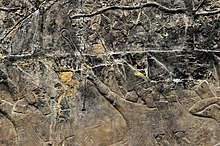

The resistance in the southern Levant was not as easily suppressed, forcing Sennacherib to invade the region. The Assyrians began with taking Ashkelon, defeating Sidqia, and then proceeded to besiege and take numerous cities. As the Assyrians were preparing to retake Ekron, Hezekiah's ally Egypt intervened in the conflict, however the Egyptian expedition was defeated in battle near the city Eltekeh. The cities of Ekron and Timnah were taken and Judah stood alone, with Sennacherib setting his sight on Jerusalem.[34] While a portion of Sennacherib's troops prepared to blockade Jerusalem, Sennacherib himself marched on the important Judean city Lachish. Both the blockade of Jerusalem and the siege of Lachish probably served to prevent further Egyptian aid from reaching Hezekiah and to intimidate the kings of other smaller states in the region. The siege of Lachish, which ended in the city's destruction, was so long that the defenders eventually began using arrows made of bone rather than metal due to lack of supply. In order to take the city, the Assyrians constructed a great siege mound, essentially a ramp made of stone and earth, to reach the top of Lachish's walls. After the city was destroyed, survivors were deported into the Assyrian Empire. Some of them were forced to aid in Sennacherib's building projects and others were employed in the king's personal guard.[36]

Sennacherib at the gates of Jerusalem[edit]

Sennacherib's account of what happened at Jerusalem begins with "As for Hezekiah ... like a caged bird I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city. I barricaded him with outposts, and exit from the gate of his city I made taboo for him". As such, Jerusalem was blockaded in some capacity, though the lack of massive military activities and appropriate equipment means that it was probably not a full siege.[37] According to the narrative of the event laid out in the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible, a senior Assyrian official with the title Rabshakeh stood in front of the city's walls and demanded its surrender.[38] Allegedly, the Rabshakeh used the phrase "eat feces and drink urine" to threaten the Judeans with the difficult conditions that they were soon to experience.[39] Although the Assyrian account of the operation may lead one to believe that Sennacherib was present in person, this is never explicitly stated and reliefs depicting the campaign show Sennacherib as seated on a throne in Lachish instead of overseeing the preparations for an assault on Jerusalem. According to the biblical account, Sennacherib's threatening representatives to Hezekiah found Sennacherib engaged in a struggle with the city Libnah upon their return to the king, who remained at Lachish.[40]

The account of the blockade erected around Jerusalem is different from the sieges described in Sennacherib's annals and the massive reliefs in Sennacherib's palace at Nineveh which depict the Levantine campaign show the successful siege of Lachish rather than what transpired at Jerusalem. Though the blockade of Jerusalem was not a proper siege, it is clear from all available sources that a massive Assyrian army was encamped in the city's vicinity, probably on its northern side.[41]

Though it is clear that the blockade of Jerusalem ended without significant fighting, how it was resolved and what stopped Sennacherib's massive army from overwhelming the city is uncertain. The Biblical account of the end of Sennacherib's attack on Jerusalem holds that though Hezekiah's soldiers manned the walls of the city, ready to defend it against the Assyrians, an entity referred to as the destroying angel, sent by Yahweh, annihilated Sennacherib's army, killing 185,000 Assyrian soldiers in front of Jerusalem's gates.[42] The ancient Greek historian Herodotus describe the operation being an Assyrian failure due to a "multitude of field-mice" descending upon the Assyrian camp, devouring crucial material such as quivers and bowstrings, making the Assyrians unarmed and causing them to flee.[40] It is possible that the story of the mice infestation is an allusion to some kind of disease striking the Assyrian camp, possibly the septicemic plague.[43] The battle being an outright Assyrian defeat is considered unlikely, especially on account of contemporary Babylonian chronicles, otherwise eager to mention Assyrian failures, being silent on the matter.[44]

Despite the seemingly inconclusive end to the blockade of Jerusalem, the Levantine campaign was largely an Assyrian victory. After the Assyrians had successfully seized many of Judah's most important fortified cities and destroyed several towns and villages, Hezekiah realized that his anti-Assyrian activities had been disastrous military and political miscalculations and as such submitted to the Assyrians once more. He was forced to pay a heavier tribute than previously, probably alongside a heavy penalty and the tribute which he had failed to send to Nineveh from 705 to 701 BC.[20] He was also forced to release the imprisoned king of Ekron, Padi,[44] and Judah lost a substantial amount of territory in the aftermath of the campaign, with Sennacherib granting portions of its land to the neighboring kingdoms of Gaza, Ashdod and Ekron.[45]

Resolving the Babylonian problem[edit]

Sennacherib's victory in the Levant had not been as conclusive and decisive as most Assyrian victories, which may have encouraged the vassal king of Babylon, Bel-ibni, to listen to the Elamites and Marduk-apla-iddina.[44] Because Marduk-apla-iddina continued to be active in Babylonia, Sennacherib campaigned against the south again in 700 BC and removed Bel-ibni from the throne, either due to complicity or incompetence.[25] Sennacherib's hunt for Marduk-apla-iddina was so furious that the Chaldean escaped on boats with his people and treasury across the Persian Gulf, taking refuge in the Elamite city of Nagitu. Victorious, Sennacherib attempted yet another method to govern Babylonia and appointed his son Ashur-nadin-shumi to reign as Babylonian vassal king.[46]

Ashur-nadin-shumi was also titled as māru rēštû, a title that could be interpreted either as the "pre-eminent son" or the "firstborn son". His appointment as king of Babylon and the new title suggests that Ashur-nadin-shumi was being groomed to succeed Sennacherib as the King of Assyria upon his death. Ashur-nadin-shumi being titled as the māru rēštû likely means that he was Sennacherib's crown prince; if it means "pre-eminent" such a title would be befitting only for the crown prince and if it means "firstborn", it also suggests that Ashur-nadin-shumi was the heir as the Assyrians in most cases followed the principle of primogeniture, wherein the oldest son inherits.[47] More evidence in favor of Ashur-nadin-shumi being the crown prince is Sennacherib's construction of a palace for him at the city of Assur,[48] something Sennacherib would also do for the later crown prince Esarhaddon. As an Assyrian King of Babylon, Ashur-nadin-shumi's position was politically important and highly delicate and would have granted valuable experience to him as the intended heir to the entire Neo-Assyrian Empire.[49]

In the years that followed, Babylonia stayed relatively quiet and Sennacherib campaigned elsewhere. His fifth campaign in 699 BC was composed of a series of raids against the villages around the foot of Mount Judi, located to the northeast of Nineveh. Other small campaigns were also led by Sennacherib's general without the king present, including a 698 BC expedition against Kirua, a revolting Assyrian governor in Cilicia, and a 695 BC campaign against the city Tegarama for which the cause is unknown. Throughout these years, the survival of Marduk-apla-iddina likely represented a thorn in Sennacherib's side, so he decided to invade Elam in 694 BC in pursuit of his Chaldean enemies.[46]

The Elamite campaign and revenge[edit]

In preparation for an invasion of Elam, aimed at capturing the escaped Chaldeans rather than defeating the Elamites themselves, Sennacherib had for some time overseen the construction of a great fleet by Phoenician shipbuilders in the northern parts of the Euphrates and in Nineveh, by the Tigris. The ships, manned by sailors from Tyre, Sidon and Cyprus, then transported large portions of the Assyrian army to the city Opis. At Opis, the ships were pulled ashore and transported overland on rollers or sledges to the Arahtu canal, perhaps because the lower portions of the two rivers were under Elamite influence. Where the Arahtu joined with the Euphrates south of Babylon, the troops embarked and marched to the mouth of the river. Sennacherib was not present on the boats, marching the entire distance from Nineveh to the mouth of the Euphrates.[46] From the city Bab-Salemeti, Sennacherib then joined the rest of the army and sailed across the Persian Gulf. Though the journey took five days and was apparently difficult, with repeated sacrifices being made to Ea, the god of the deep, the Assyrians successfully landed at the Elamite coast.[50]

Though they faced heavy resistance, Sennacherib's forces prevailed and took several cities, an event the king describes in his own records as a "great victory". The many captured Chaldeans and Elamites were apportioned among his soldiers. Though Sennacherib had his revenge against Marduk-apla-iddina, his arch-enemy had not lived the see it, seemingly dying of natural causes shortly before. The campaign was not a total success, as Shutur-Nahhunte's successor as king of Elam, Hallushu-Inshushinak, exacted his revenge for the invasion by striking at Babylonia.[50] Wishing to restore their independence, some of the Babylonians then seized their king Ashur-nadin-shumi at the city Sippar and handed him over to the Elamites whereafter Ashur-nadin-shumi was taken to Elam and never heard from again, probably being executed.[51][52] In his stead, the Elamites proclaimed a native Babylonian, Nergal-ushezib, as the king of Babylon.[51]

Sennacherib's position, cut off from his own empire by both Elam and Babylonia, was disadvantageous and the Elamite-Babylonian alliance was initially successful. In June or July of 694 BC, Nergal-ushezib captured the city Nippur, however three months later the Assyrians took Uruk, shortly thereafter turning the war decisively in their favor. In 693 BC, Negal-ushezib and the Elamites attacked the Assyrian army near Nippur but were defeated and Nergal-ushezib was taken as a prisoner to Nineveh. Shortly thereafter, a rebellion broke out in Elam, and three weeks after the defeat at Nippur, Hallushu-Inshushinak was replaced as Elamite king by Kutir-Nahhunte III. Even then, the Babylonians did not surrender and instead proclaimed the Chaldean Mushezib-Marduk as their new king. Before moving to deal with this problem, Sennacherib was determined to defeat Elam. Though the Assyrians captured and destroyed 46 cities, the Elamites refused to fight them, retreating with their new king into the mountains. The oncoming winter, combined with snow and rain, stopped Sennacherib from pursuing them and he returned to Nineveh.[50]

Destruction of Babylon[edit]

After reigning for just ten months, Kutir-Nahhunte III was replaced as king of Elam by Humban-Numena III and Sennacherib decided that the time had come to decisively defeat his southern enemies. With the threat of Assyrian invasion looming, the Babylonians quickly ensured the continued support of Elam by bribing the new Elamite king with valuables they stripped from their great temple dedicated to their god Marduk.[50] The Assyrian records consider Humban-Numena's decision to support Babylon as unintelligent, describing him as a "man without any sense or judgement".[53] In 691 BC, Mushezib-Marduk's anti-Assyrian coalition struck against Sennacherib. Humban-Numena and his commander, Humban-undasha, led the forces of the coalition against Sennacherib in the Battle of Halule, the outcome of which is uncertain. Both Babylonian and Assyrian texts claim the battle as a great victory. Since Assyrian texts do not mention events in the south again until the later siege of Babylon, it is more likely that the southerners won, though likely suffering large casualties. Sennacherib returned to Nineveh with both of his enemies still on their respective thrones.[54][55]

In 690 BC, Humban-Numena suffered a stroke and his jaw became locked in a way that prevented him from speaking. Taking advantage of the situation, Sennacherib embarked on his final campaign against Babylon.[55] Although the Babylonians were initially successful, that was short-lived, and in that same year, a siege of Babylon was already well underway.[54] Babylon would likely have been in a poor condition once it fell to Sennacherib in 689 BC, having been besieged for over fifteen months. The king who had anxiously considered the implications of Sargon's seizure of Babylon and the role that the city's offended gods may have played in his father's downfall was gone, replaced by a king wishing to avenge the death of his son and tiring of a city well within the borders of his empire which had repeatedly rebelled against his rule. He had no affection for gods who had inspired their populace to attack him and Sennacherib decided to destroy the city. Sennacherib's own account of the destruction reads as follows:[56]

Into my land I carried off alive Mušēzib-Marduk, king of Babylonia, together with his family and officials. I counted out the wealth of that city – silver, gold, precious stones, property and goods – into the hands of my people; and they took it as their own. The hands of my people laid hold of the gods dwelling there and smashed them; they took their property and goods.

I destroyed the city and its houses, from foundation to parapet; I devastated and burned them. I razed the brick and earthenwork of the outer and inner wall of the city, of the temples, and of the ziggurat; and I dumped these into the Araḫtu canal. I dug canals through the midst of that city, I overwhelmed it with water, I made its very foundations disappear, and I destroyed it more completely than a devastating flood. So that it might be impossible in future days to recognize the site of that city and its temples, I utterly dissolved it with water and made it like inundated land.[56]

Although Sennacherib destroyed the city, he was still somewhat fearful of Babylon's ancient gods. Earlier in his account of the campaign he specifically mentions that the sanctuaries of the Babylonian deities had provided financial support to his enemies and the passage in which the seizure of the property of the gods and the destruction of some of their statues is described is one of the few in which Sennacherib uses "my people" rather than "I".[56] This leaves the blame of the fate of the temples not on Sennacherib himself, but on the decisions made by the temple personnel and the actions of the Assyrian people rather than the king in particular.[57]

During the destruction of the city, Sennacherib destroyed the temples and the images of the gods, except for that of Marduk, which he took to Assyria.[58] This caused consternation in Assyria itself, where Babylon and its gods were held in high esteem.[59] Sennacherib attempted to justify his actions to his own countrymen through a campaign of religious propaganda.[60] Among the elements of this campaign he commissioned a myth in which Marduk was put on trial before Ashur, the god of Assyria. This text is fragmentary but it seems Marduk is found guilty of some grave offense;[61] he described his defeat of the Babylonian rebels in the language of the Babylonian creation myth, identifying Babylon with the evil demon-goddess Tiamat and himself with Marduk;[62] Ashur replaced Marduk in the New Year's festival; and in the temple of the festival he placed a symbolic pile of rubble from Babylon.[63] In Babylonia, Sennacherib's policy spawned a deep-seated hatred amongst much of the populace.[64]

Sennacherib's goal was the complete eradication of the Babylonia as a political entity.[65] Though some northern Babylonian territories were turned into Assyrian provinces, the Assyrians made no effort to rebuild Babylon itself and southern chronicles from the time refer to the era as the "kingless" period when there was no king in the land.[57]

Construction of Nineveh[edit]

After the final war with Babylon, Sennacherib seemingly spent the rest of his reign in peace, dedicating his time to improving his new capital at Nineveh rather than embarking on large military campaigns.[55] Nineveh had been an important city in northern Mesopotamia for millennia. The oldest traces of human settlement at its location are from the 7th millennium BC and from the 4th millennium BC and onwards it formed an important administrative center in the north.[66] When Sennacherib made the city his new capital it experienced one of the most ambitious building projects in ancient history, being completely transformed from the somewhat neglected state the city had been in before his reign.[67]

The earliest inscriptions discussing the building project at Nineveh date to 702 BC and are about the construction of the Southwest Palace, a large residence constructed in the city's southwestern parts.[24] Sennacherib called this palace the ekallu ša šānina la išu, the "Palace without Rival".[68] During the construction process, a previous smaller palace was torn down, a stream of water which had been eroding parts of the palace mound was redirected and a terrace which the new palace was to stand on was erected and raised to the height of 160 layers of brick. Though many of these early inscriptions talk about the palace as if it was already completed, this was the standard way of writing about building projects in ancient Assyria. The Nineveh described in Sennacherib's earliest accounts of its construction was a city with at that point only existed in his imagination.[24]

By 700 BC the walls of the Southwest Palace's throne room were being constructed, followed shortly thereafter by the many reliefs that were to be displayed within it. After the reliefs were done, the final step in the construction of the palace was the erection of great colossal statues depicting bulls and lions, characteristic of Late Assyrian architecture. Though such statues in stone have been excavated at Nineveh, similar colossal statues mentioned in the inscriptions as being made of precious metals remain missing. The roof of the palace was constructed with cypress and cedar recovered from the mountains in the west and the palace was illuminated through multiple windows and decorated with silver and bronze pegs on the inside and glazed bricks on the outside. The full structure, going by the mound it was built on, measured 450 metres (1476 ft) long and 220 metres (722 ft) wide. An inscription on a stone lion in the quarter associated with Sennacherib's queen, Tashmetu-sharrat, contains hopes that the king and queen would both live long and healthy lives within the new palace.[69] The text of the inscription reads:[70]

And for the queen Tashmetu-sharrat, my beloved wife, whose features Belet-ili has made more beautiful than all other women, I had a palace of love, joy and pleasure built. … By the order of Ashur, father of the gods, and heavenly queen Ishtar may we both live long in health and happiness in this palace and enjoy wellbeing to the full![70]

Though probably conceived as a structure similar to the palace Sargon built at Dur-Sharrukin, Sennacherib's palace, and especially the artwork featured therein shows some differences. Though Sargon's reliefs usually show the king as close to other members of the Assyrian aristocracy, Sennacherib's art usually depicts the king towering above everyone else in his vicinity due to being mounted in a chariot. His reliefs show larger scenes, some almost from a birds-eye point of view. There are also examples of a more naturalistic approach in the art; where colossal statues of bulls from Sargon's palace depicts them with five legs so that four legs could be seen from either side and two from the front, Sennacherib's bulls all have four legs.[69] Sennacherib constructed beautiful gardens at his new palace, importing various plants and herbs from throughout his empire and beyond. Cotton plants may have been imported from as far away as India. It has been suggested that the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, where actually these gardens in Nineveh, but the presence of impressive royal gardens in Babylon itself makes this idea somewhat unlikely.[71]

In addition to the palace, Sennacherib oversaw other building projects at Nineveh. He built a large second palace at the city's southern mound, which served as an arsenal to store military equipment and also as permanent quarters for portions of the Assyrian standing army. Numerous temples were built and restored, many of them on the Kuyunjik mound (where the Southwest Palace was located), including a temple dedicated to the god Sîn (invoked in the king's own name). Furthermore, Sennacherib massively expanded the city to the south and erected new huge and massive city walls, surrounded by a moat, up to 25 metres (82 ft) high and 15 metres (49 ft) thick.[71]

Conspiracy, murder and succession[edit]

When his eldest son and original crown prince Ashur-nadin-shumi disappeared, presumably executed, Sennacherib selected his eldest surviving son, Arda-Mulissu, as the new crown prince. Arda-Mulissu held the position of heir apparent for several years until he suddenly was replaced as heir by his younger brother Esarhaddon in 684 BC. The reason for Arda-Mulissu's sudden dismissal from the prominent position is unknown, but it is clear from contemporary inscriptions that he was very disappointed.[72] Esarhaddon's influential mother Naqi'a may have played a role in convincing Sennacherib to pick Esarhaddon as heir.[73] Despite his dismissal, Arda-Mulissu remained a popular figure and some vassals secretly supported him as the heir to throne.[74]

Arda-Mulissu was forced to swear loyalty to Esarhaddon by his father, but made many appeals to Sennacherib to reinstated as heir.[72] Sennacherib noted the increasing popularity of Arda-Mulissu and came to fear for his designated successor, so he sent Esarhaddon away to the western provinces. This exile of Esarhaddon put Arda-Mulissu in a difficult position as he had reached the height of his popularity but was powerless to do anything to Esarhaddon. In order to use the opportunity, Arda-Mulissu decided that he needed to act quickly and take the throne by force.[74] Arda-Mulissu concluded a "treaty of rebellion" with another of his younger brothers, Nabu-shar-usur, and on 20 October 681 BC, they attacked and killed their father in one of Nineveh's temples,[72] possibly the temple dedicated to Sîn.[71]

The murder of Sennacherib, ruler of one of the strongest empires on the planet at his time, was shocking to his contemporaries and was received with strong emotion and mixed feelings throughout Mesopotamia and the rest of the Ancient Near East. In the Levant and in Babylonia the news were celebrated and proclaimed as divine punishment due to Sennacherib's brutal campaigns against them while in Assyria, the reaction was probably resentment and horror. The event was recorded in numerous sources and is even mentioned in the Bible (2 Kings 19:37; Isaiah 37:38), wherein Arda-Mulissu is called Adrammelech.[74]

Despite the success of their conspiracy, Arda-Mulissu couldn't successfully seize the throne. The murder of the king caused some resentment against Arda-Mulissu by his own supporters which delayed his potential coronation and in the meantime, Esarhaddon had raised an army. The army raised by Arda-Mulissu and Nabu-shar-usur met Esarhaddon's forces at Hanigalbat, a city in the western parts of the empire. There, most of their soldiers deserted and joined Esarhaddon, who then marched on Nineveh without opposition, becoming the new king of Assyria. Shortly after taking the throne, Esarhaddon executed all conspirators and political enemies within his reach, including the families of his brothers. All servants involved with the security of the royal palace at Nineveh were executed. Arda-Mulissu and Nabu-shar-usur survived this purge as they had escaped as exiles to the northern kingdom of Urartu.[72]

Family and children[edit]

As was traditional for Assyrian kings, Sennacherib had a harem of many women. Two of his wives are known by name; Tashmetu-sharrat (Akkadian: Tašmetu-šarrat)[75] and Naqi'a. Whether both of the women held the position of queen or not is uncertain, but contemporary sources suggest that though the kings had multiple women, only one would be recognized as queen and primary consort at one time. For most of Sennacherib's reign, the queen was Tashmetu-sharrat, whose name literally means "Tashmetum is queen".[11] Inscriptions suggest that Sennacherib and Tashmetu-sharrat had a loving relationship, with the king referring to her as "my beloved wife" and publicly praising her beauty.[75]

Whether Nagi'a ever held the title of queen is not clear, she was referred to as the "queen mother" during Esarhaddon's reign but as she was Esarhaddon's mother, the title may have been bestowed on her either late in Sennacherib's reign or by Esarhaddon.[11] Though Tashmetu-sharrat was the primary consort for longer, Naqi'a is more well known today due to her role during Esarhaddon's reign. When she became one of Sennacherib's wives, she took the Akkadian name Zakûtu (Naqi'a being an Aramaic name). Naqi'a having two names could point to her originating outside of Assyria proper, possibly in Babylonia or in the Levant, but there is no substantial evidence for any theory regarding her origin.[73]

Sennacherib had at least seven sons and at least one daughter. With the exception of Esarhaddon (who is known to be the son of Naqi'a), which of Sennacherib's wives were the mothers of his children is unknown. Tashmetu-sharrat is likely to have been the mother of at least some of them.[76] Their names were:

- Ashur-nadin-shumi (Akkadian: Aššur-nādin-šumi)[47] – probably Sennacherib's eldest son. Appointed king of Babylon and crown prince in 700 BC, serving as both until his capture and execution by the Elamites in 694 BC.[77]

- Ashur-ili-muballissu (Akkadian: Aššur-ili-muballissu)[75] – probably Sennacherib's second eldest son (he is called māru terdennu, meaning "second son"). Mentioned as being "begotten at the feet of Ashur", suggesting that he held som role in the priesthood.[75] Known to have been given a house at Assur, probably at some point before 700 BC, by his father and to have been given a precious vase later excavated at Nineveh.[78]

- Arda-Mulissu (Akkadian: Arda-Mulišši)[79] – Sennacherib's eldest living son by the time of Ashur-nadin-shumi's death in 694 BC, served as his crown prince from 694 BC until 684 BC, when he for unknown reasons was replaced as heir by Esarhaddon. Orchestrated the 681 conspiracy which ended in Sennacherib's death in hopes of taking the throne for himself.[72] After his troops were defeated by Esarhaddon, he escaped to Urartu where he might have been alive as late as 673 BC.[80]

- Ashur-shumu-ushabshi (Akkadian: Aššur-šumu-ušabši) – a son whose place in Sennacherib's sequence of children is unknown. He was given a house in Nineveh by Sennacherib. Bricks bearing inscriptions discussing the construction of this house were later excavated at Nineveh, possibly indicating that Ashur-shumu-ushabshi had died before the house was completed.[78]

- Esarhaddon (Akkadian: Aššur-aḫa-iddina)[81] – a younger son who served as Sennacherib's crown prince 684–681 BC and succeeded him as the king of Assyria, reigning 681–669 BC.[72]

- Nergal-shumu-ibni (Akkadian: Nergal-šumu-ibni) – the reconstructed name (the full name of the prince being missing in the inscriptions) of another son of Sennacherib, mentioned as having employed a large staff, including a personal horse raiser called Sama'. Might be the same person as an information officer by the same name mentioned in 683 BC. His name might alternatively be reconstructed as Nergal-shumu-usur.[78]

- Nabu-shar-usur (Akkadian: Nabû-šarru-uṣur)[82] – a younger son who joined Arda-Mulissu in his plot to murder Sennacherib and seize power. Escaped with Arda-Mulissu to Urartu, where he might have been alive as late as 673 BC.[72][80]

- Shadditu (Akkadian: Šadditu)[78] – the only of Sennacherib's daughters known by name, Shadditu appears in land sale documents and protective rituals were conducted on her behalf. She was probably a daughter of Naqi'a as she retained a place in the royal family during Esarhaddon's reign. She or another daughter was married to an Egyptian noble called Shushanqu in 672 BC.[76]

A small tablet excavated at Nineveh lists the names of mythological Mesopotamian heroes, such as Gilgamesh, and some personal names. As the name Ashur-ili-muballissu appears in the list of personal names, alongside fragmentary names that could possibly be reconstructed as Ashur-nadin-shumi (or Ashur-shumu-ushabshi) and Esarhaddon, it is also possible that the other personal names were names of further sons of Sennacherib. These names include Ile''e-bullutu-Aššur, Aššur-mukkaniš-ilija, Ana-Aššur-taklak, Aššur-bani-beli, Samaš-andullašu (or Samaš-salamšu) and Aššur-šakin-liti.[78]

Character[edit]

The main sources that can be used to deduce Sennacherib's personality are his royal inscriptions. However, these inscriptions were not actually written by the king himself, but rather his royal scribes, and often served as propaganda meant to portray the king as better than all other rulers, both contemporary and ancient.[83] Furthermore, Assyrian royal inscriptions often only explore military and construction matters and were highly formulaic, differing little from king to king.[84] However, by examining the inscriptions and comparing them to those of other kings and of non-royal inscriptions, it is possible to assume some aspects of Sennacherib's character. As in the inscriptions of other Assyrian kings, Sennacherib's inscriptions show pride and high self-esteem, for instance in the passage "Ashur, father of the gods, looked steadfastly upon me among all the rulers and he made my weapons greater than (those of) all who sit on (royal) daises". In several places, the great intelligence of Sennacherib is emphasized, for instance, the passage "the god Ninshiku gave me wide understanding equal to (that of) the sage Adapu (and) endowed me with broad knowledge". In several inscriptions he is explicitly referred to as "foremost of all rulers" (ašared kal malkī) and a "perfect man" (eṭlu gitmālu).[82][83] Sennacherib's decision to keep his birth name when he became king, rather than assuming a throne name, something at least 19 of his 21 immediate predecessors had done, suggests a certain degree of self-confidence. Sennacherib assumed several new epithets never before used by Assyrian kings, such as "guardian of the right" and "lover of justice", suggesting a desire to leave a personal mark on a new era beginning with his reign.[23]

When Sennacherib became king he was already an adult and had served as Sargon's crown prince for over 15 years. He would thus have been well acquainted with the administration of the empire. Unlike many preceding and later Assyrian kings (including his father), Sennacherib did not portray himself as a conqueror or express much desire in conquering the world. Instead, his inscriptions often portrayed the most important parts of his reign as his large-scale building projects. Most of Sennacherib's campaigns were not aimed at conquest but at suppressing revolts against his rule, restoring lost territories and securing treasure to finance his building projects.[85] As can be seen in several of Sennacherib's campaigns being led by his generals rather than the king in person, Sennacherib was not as interested in campaigning as his predecessors had been.[86] The brutal retribution and punishment served to Assyria's enemies as described in Sennacherib's accounts do not necessarily reflect the truth as these accounts also served as propaganda and psychological warfare through intimidation.[87]

Despite the apparent lack of interest in world domination, Sennacherib did assume the traditional Mesopotamian titles that designated rule of the entire world; "king of the universe" and "king of the four corners of the world". Other titles, such as "strong king" and "mighty king", emphasized his power and greatness, alongside epithets such as "virile warrior" (zikaru qardu) and "fierce wild bull" (rīmu ekdu).[85] All Sennacherib's campaigns were described as victories in his own accounts, even the unsuccessful ones. This was not necessarily due to personal pride; a failed campaign would have been regarded by his subjects as an indication that the gods no longer favored Sennacherib's rule.[85] Sennacherib was fully convinced that the gods supported him and saw all his wars as just for this reason.[86] The enemies of Assyria were seen as people who did not respect the gods and they were thus treated and punished as criminals.[88]

It is possible that Sennacherib suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder due to the catastrophic fate of his father. From the available sources, it does appear that Sennacherib was easily enraged by bad news and that he developed serious psychological problems over time. Sennacherib's son and successor Esarhaddon mentions in his inscriptions that Sennacherib was afflicted with the "alû demon" and that none of Sennacherib's diviners initially dared to tell the kings that signs pointing to the demon had been observed.[28] What the alû demon was is not entirely understood, but the typical symptoms described in contemporary documents include the afflicted not knowing who they are, their pupils constricting, their limbs being tense, being incapable of speech and their ears roaring.[23]

Assyriologists Julian E. Reade and Eckart Frahm have pondered the idea that Sennacherib could be classified as a feminist. Female members of the court were more prominent and enjoyed greater privileges under Sennacherib's reign than under the reigns of previous Assyrian kings. The reasons for Sennacherib's policy towards his female relatives are unknown. It might be due to a desire to shift power away from powerful generals and magnates to his own family, due to encounters with powerful Arabian queens who made their own decisions and led armies or as a way to compensate for the way he treated his father's memory. Evidence to the increased standing of the royal women includes the increased amount of texts referencing Assyrian queens from Sennacherib's reign compared to queens of earlier times and evidence that the queens of Sennacherib had their own standing military units, just like the king. Mirroring the increased standing of the women of the royal family, female deities were also depicted more frequently during the time of Sennacherib. For instance, the god Ashur is frequently depicted together with a female companion, probably the goddess Mullissu.[89]

Legacy[edit]

Sennacherib in popular memory[edit]

Throughout the milllennia that followed Sennacherib's death, the popular image of the king has been mainly negative. There are two primary reasons for this, the first being Sennacherib's negative portrayal in the Bible, as the evil conqueror who attempted to take Jerusalem, and the second being his destruction of Babylon, one of the most prominent cities in the ancient world. This negative view of Sennacherib endured until modern times. In the famous 1815 poem The Destruction of Sennacherib by Lord Byron, Sennacherib is presented as akin to a ruthless predator, attacking Judah as a "wolf on the fold":[90]

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold,

And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;

And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea,

When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee.

Sennacherib's 701 BC attack against Jerusalem was a "world event", drawing together the fates of numerous otherwise disparate groups. The event and its aftermath affected and had consequences for not only the Assyrians and the Israelites, but also the Babylonians, Egyptians, Nubians, Syro-Hittites and Anatolian peoples. The siege is discussed not only in contemporary sources but also in later folklore and traditions, such in Aramaic folklore, in later Greco-Roman histories on the Near East and in the tales of medieval Syriac Christians and Arabs.[91] Sennacherib's Levantine campaign is a significant event in the Bible, being brought up and discussed in numerous places, notably 2 Kings 18:13–19:37, 20:6 and Chronicles 32:1–23.[92] A vast majority of the Biblical account of King Hezekiah's reign in 2 Kings is dedicated to Sennacherib's campaign, cementing it as the most important event of Hezekiah's time.[93] In Chronicles, the failure of Sennacherib and the success of Hezekiah is emphasized, the Assyrian campaign (described as an act of aggression rather than as a response to Hezekiah's rebellious activities) is seen as doomed to fail from the start. According to the narrative, no enemy, not even the powerful king of Assyria, would have been able to triumph over Hezekiah as the Judean king had God on his side.[94] The conflict is presented as something akin to a holy war; God's war against the pagan Sennacherib.[95]

Though Assyria had more than a hundred kings throughout its long history, Sennacherib (alongside his son Esarhaddon and grandsons Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin) is one of the few kings who were remembered and figured in Aramaic and Syriac folklore long after the kingdom had fallen. In the ancient Aramaic story of Ahikar, Sennacherib is portrayed as a benevolent patron of the titular character Ahikar, with his son Esarhaddon being portrayed more negatively. In medieval Syriac tales, Sennacherib is characterized as an archetypical pagan king who is assassinated as part of a family feud and whose children convert to Christianity.[96] In the legend of the 4th-century Saints Behnam and Sarah, Sennacherib, under the name Sinharib, is cast as the royal father of Behnam and Sarah. After Behnam converts to Christianity, Sinharib orders his execution but is later struck by a dangerous disease that is cured through being baptized by Saint Matthew in Assur. Thankful, Sinharib then converts to Christianity and founds an important monastery near Mosul, called Deir Mar Mattai.[97]

In later Jewish tradition, Sennacherib also occupied various roles. In Midrash, similar examinations of the Old Testament and later stories, the events of 701 BC are often explored in detail; often featuring massive armies deployed by Sennacherib and pointing out how Sennacherib repeatedly consulted astrologers on his campaign, delaying his actions. In the stories, Sennacherib's armies are destroyed when Hezekiah recites Hallel psalms on the eve of Passover. The event is often portrayed as an apocalyptic scenario, with Hezekiah portrayed as a messianic figure and Sennacherib and his armies being personifications of Gog and Magog.[98]

Archaeological discoveries[edit]

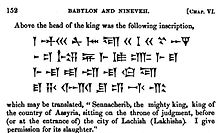

The discovery of Sennacherib's own inscriptions in the 19th century, in which brutal and cruel acts such as ordering the throats of his Elamite enemies to be slit, and their hands and lips to be cut off, amplified his already ferocious reputation. Today, an abundance of such inscriptions are known, most of them housed in the collections of the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin and the British Museum in London, though many are also scattered throughout the world in other institutions and in private collections. Some large objects with Sennacherib's inscriptions remain at Nineveh, where some have even been reburied.[99] Sennacherib's own accounts of his building projects and military campaigns typically referred to as his "annals", of his reign were often copied several times and spread throughout the Neo-Assyrian Empire during his reign. For the first six years of his reign, they were written on clay cylinders, but he later began using clay prisms, probably because they provided a greater surface area.[22]

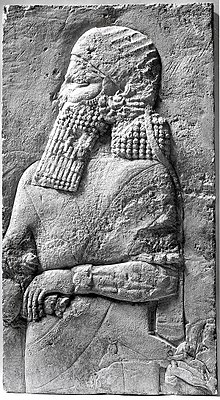

Letters associated with Sennacherib are less in number than those known from his father and from the time of his son Esarhaddon, and most of them are from Sennacherib's tenure as crown prince. Other types of non-royal inscriptions from Sennacherib's reign, such as administrative documents, economic documents and chronicles, are more numerous.[100] In addition to written sources, numerous pieces of artwork have also survived from Sennacherib's time, notably the king's reliefs from his palace at Nineveh. These reliefs typically depict his conquests, sometimes with short pieces of texts explaining the scene shown. First discovered and excavated from 1847 to 1851 by British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, the discovery of reliefs depicting Sennacherib's siege of Lachish in the Southwest Palace was the first archaeological confirmation of an event described in the Bible.[68]

Further excavations of the Southwest Palace were then led by Hormuzd Rassam and Henry Creswicke Rawlinson from 1852 to 1854, William Kennett Loftus from 1854 to 1855 and George Smith from 1873 to 1874.[68] Among the many inscriptions found at the site, Smith discovered a fragmentary account of a flood, which generated much excitement both among the general public and among scholars. Since Smith, the site has been experienced several periods of intense excavations and study; Hormuzd Rassam returned from 1878 to 1882, E. A. Wallis Budge oversaw excavations from 1889 to 1891, Leonard William King from 1903 to 1904 and Reginald Campbell Thompson in 1905 and from 1931 to 1932. The most recent expeditions were conducted by the Iraqi Department of Antiquities under T. Madhloom from 1965 to 1968. Many of Sennacherib's reliefs are today exhibited at the Vorderasiatisches Museum, the British Museum, the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Louvre in Paris.[101]

Titles[edit]

The following titulature is used by Sennacherib in early accounts of his 703 BC Babylonian campaign:[102]

Sennacherib, great king, mighty king, king of Assyria, king without rival, righteous shepherd, favorite of the great gods, prayerful shepherd, who fears the great gods, protector of righteousness, lover of justice, who lends support, who comes to the aid of the cripple and aims to do good deeds, perfect hero, mighty man, first among all kings, neckstock that bends the insubmissive, who strikes the enemy like a thunderbolt, Ashur, the great mountain, has bestowed upon me an unrivalled kingship and has made my weapons mightier than the weapons of all other rulers sitting on daises.[102]

This variant of the titulature is used in an inscription from the Southwest Palace at Nineveh written after Sennacherib's 700 BC Babylonian campaign:[103]

Sennacherib, the great king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, king of the four quarters (of the world); favorite of the great gods; the wise and crafty one; strong hero, first among all princes; the flame that consumes the insubmissive, who strikes the wicked with the thunderbolt. Assur, the great god, has intrusted to me an unrivaled kingship, and has made powerful my weapons above (all) those who dwell in palaces. From the upper sea of the setting sun to the lower sea of the rising sun, all princes of the four quarters (of the world) he has brought in submission to my feet.[103]

See also[edit]

- List of Assyrian kings

- Military history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

- Sennacherib's Annals

- Lachish reliefs

- Azekah Inscription

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

References[edit]

- ^ Elayi 2017, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Elayi 2018, p. 18.

- ^ Harmanşah 2013, p. 120.

- ^ a b Kalimi 2014, p. 11.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 12.

- ^ Mark 2014.

- ^ a b Brinkman 1973, p. 89.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 13.

- ^ Elayi 2017, p. 27.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Elayi 2018, p. 15.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 31.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 38.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Brinkman 1973, p. 90.

- ^ Frahm 2014, p. 209.

- ^ Frahm 2014, p. 208.

- ^ Frahm 2014, p. 212.

- ^ Frahm 2014, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d Kalimi 2014, p. 20.

- ^ a b Frahm 2014, p. 202.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Frahm 2014, p. 204.

- ^ a b c Frahm 2008, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brinkman 1973, p. 91.

- ^ Frahm 2002, p. 1113.

- ^ a b Frahm 2003, p. 130.

- ^ a b Frahm 2014, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Frahm 2003, p. 129.

- ^ Luckenbill 1924, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Luckenbill 1924, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Bauer 2007, p. 384.

- ^ Grayson 1991, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Luckenbill 1924, p. 11.

- ^ Matty 2016, p. 26.

- ^ Barnett 1958, pp. 161–164.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 38.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 25.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 40.

- ^ a b Luckenbill 1924, p. 12.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 39–40.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Caesar 2017, p. 224.

- ^ a b c Luckenbill 1924, p. 13.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Luckenbill 1924, p. 14.

- ^ a b Porter 1993, p. 14.

- ^ Porter 1993, p. 15.

- ^ Porter 1993, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Luckenbill 1924, p. 15.

- ^ a b Brinkman 1973, p. 92.

- ^ Bertman 2005, p. 79.

- ^ Luckenbill 1924, p. 16.

- ^ a b Brinkman 1973, p. 93.

- ^ a b c Luckenbill 1924, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Brinkman 1973, p. 94.

- ^ a b Brinkman 1973, p. 95.

- ^ Grayson 1991, p. 118.

- ^ Leick 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Grayson 1991, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Grayson 1991, p. 119.

- ^ McCormick 2002, pp. 156,158.

- ^ Grayson 1991, p. 116.

- ^ Grayson 1991, p. 109.

- ^ Frahm 2014, p. 210.

- ^ Frahm 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Frahm 2008, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Elayi 2018, p. 5.

- ^ a b Frahm 2008, p. 16.

- ^ a b Kertai 2013, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Frahm 2008, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g Radner 2003, p. 166.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Parpola 1980.

- ^ a b c d Frahm 2002, p. 1114.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 17.

- ^ Porter 1993, pp. 14–16.

- ^ a b c d e Frahm 2002, p. 1115.

- ^ Baker 2016, p. 272.

- ^ a b Barcina Pérez 2016, p. 9–10.

- ^ Postgate 2014, p. 250.

- ^ a b Frahm 2014, p. 193.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 19.

- ^ Frahm 2014, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Elayi 2018, p. 20.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 21.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 22.

- ^ Elayi 2017, p. 18.

- ^ Frahm 2014, pp. 213–217.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 1.

- ^ Kalimi & Richardson 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 21.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Kalimi & Richardson 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Radner 2015, p. 7.

- ^ Kalimi & Richardson 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 4.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 6.

- ^ a b Frahm 2003, p. 141.

- ^ a b Luckenbill 1927, p. 140.

Cited bibliography[edit]

- Baker, Robin (2016). Hollow Men, Strange Women: Riddles, Codes and Otherness in the Book of Judges. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004322660.

- Barcina Pérez, Cristina (2012). "Display Practices in the Neo-Assyrian Period". Universiteit Leiden - Research Master in Assyriology.

- Barnett, R. D. (1958). "The Siege of Lachish". Israel Exploration Journal. 8 (3): 161–164. JSTOR 27924740.

- Bauer, Susan Wise (2007). The History of the Ancient World: From the Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393059748.

- Bertman, Stephen (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195183641.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1973). "Sennacherib's Babylonian Problem: An Interpretation". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 25 (2): 89–95. doi:10.2307/1359421. JSTOR 1359421.

- Caesar, Stephen W. (2017). "The Annihilation of Sennacherib's Army: A Case of Septicemic Plague" (PDF). Jewish Bible Quarterly. 45 (4): 222–228.

- Elayi, Josette (2017). Sargon II, King of Assyria. Atlanta: SBL Press. ISBN 978-1628371772.

- Elayi, Josette (2018). Sennacherib, King of Assyria. Atlanta: SBL Press. ISBN 978-0884143178.

- Frahm, Eckart (2002). "Sîn-ahhe-eriba". In Baker, Heather D. (ed.). The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Vol. 3, Part. I: P-S. Helsinki: The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project.

- Frahm, Eckart (2003). "New sources for Sennacherib's "first campaign"". Isimu. 6: 129–164.

- Frahm, Eckart (2008). "The Great City: Nineveh in the Age of Sennacherib". Journal of the Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies. 3: 13–20.

- Frahm, Eckart (2014). "Family Matters: Psychohistorical Reflections on Sennacherib and His Times". In Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (eds.). Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004265615.

- Grayson, A.K. (2003) [1991]. "Assyria: Sennacherib and Essarhaddon". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III Part II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521227179.

- Harmanşah, Ömür (2013). Cities and the Shaping of Memory in the Ancient Near East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107533745.

- Kalimi, Isaac (2014). "Sennacherib's Campaign to Judah: The Chronicler's View Compared with his "Biblical" Sources". In Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (eds.). Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004265615.

- Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (2014). "Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography: An Introduction". In Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (eds.). Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004265615.

- Kertai, David (2013). "The Queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire". Altorientalische Forschungen. 40 (1): 108–124. doi:10.1524/aof.2013.0006.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2009). Historical Dictionary of Mesopotamia. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810863248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1924). The Annals of Sennacherib. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 506728.

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1927). Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 926853184.

- McCormick, Clifford Mark (2002). Palace and Temple: A Study of Architectural and Verbal Icons. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110172775.

- Matty, Nazek Khalid (2016). Sennacherib's Campaign Against Judah and Jerusalem in 701 B.C.: A Historical Reconstruction. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110447880.

- Porter, Barbara N. (1993). Images, Power, and Politics: Figurative Aspects of Esarhaddon's Babylonian Policy. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871692085.

- Postgate, Nicholas (2014). Bronze Age Bureaucracy: Writing and the Practice of Government in Assyria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107043756.

- Radner, Karen (2003). "The Trials of Esarhaddon: The Conspiracy of 670 BC". ISIMU: Revista sobre Oriente Próximo y Egipto en la antigüedad. 6: 165–183.

- Radner, Karen (2015). Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198715900.

Cited web sources[edit]

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014). "Sennacherib". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Parpola, Simo (1980). "The Murderer of Sennacherib". Gateways to Babylon. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sennacherib. |

- Daniel David Luckenbill's The Annals of Sennacherib (1924), containing complete translations of Sennacherib's annals, Sennacherib's own records of his reign.

- Daniel David Luckenbill's Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End (1927), containing translations of a large number of Sennacherib's inscriptions (pages 115–198).

Sennacherib Born: c. 745 BC Died: 20 October 681 BC

| ||

| Preceded by Sargon II |

King of Assyria 705 – 681 BC |

Succeeded by Esarhaddon |

| King of Babylon 705 – 704/703 BC |

Succeeded by Marduk-zakir-shumi II | |

| Preceded by Mushezib-Marduk |

King of Babylon (de facto, Babylon destroyed) 689 – 681 BC |

Succeeded by Esarhaddon |

- Neo-Assyrian Empire

- Sennacherib

- Sargonid dynasty

- 8th-century BC births

- 681 BC deaths

- 7th-century BC murdered monarchs

- 8th-century BC Assyrian kings

- 7th-century BC Assyrian kings

- 8th-century BC Babylonian kings

- 7th-century BC Babylonian kings

- Assyrian kings

- Biblical murder victims

- Male murder victims

- Monarchs of the Hebrew Bible

- Kings of the Universe