Second Temple

| Second Temple Herod's Temple | |

|---|---|

בית־המקדש השני | |

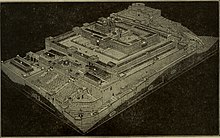

Model of Herod's Temple (a renovation of the Second Temple) in the Israel Museum, created in 1966 as part of the Holyland Model of Jerusalem. The model was inspired by the writings of Josephus. | |

| Religion | |

| Deity | Yahweh |

| Location | |

| Location | Herodian Temple Mount, Jerusalem |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°46′41″N 35°14′07″E / 31.778013°N 35.235367°E |

| Architecture | |

| Creator | Likely Zerubbabel, largely renovated by Herod the Great. |

| Destroyed | 70 CE |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | 45.72 metres (150.0 ft) |

| Materials | local limestone |

| Parent listing | Second Temple |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 537–516 BCE (construction) |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1930, 1967, 1968, 1970–1978, 1996–1999, 2007 |

| Archaeologists | Charles Warren, Benjamin Mazar, Ronny Reich, Eli Shukron, Yaakov Billig |

| Condition | Ruin, archaeological park |

| Ownership | Disputed, currently managed by the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf |

| Public access | Yes (limited) |

The Second Temple (בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ הַשֵּׁנִי, Beit HaMikdash HaSheni) was the Jewish holy temple which stood on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem during the Second Temple period, between 516 BCE and 70 CE. It replaced Solomon's Temple (the First Temple),[1] which was destroyed by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE, when Jerusalem was conquered and part of the population of the Kingdom of Judah was taken into exile to Babylon.

The Second Temple was originally a rather modest structure constructed by a number of Jewish exile groups returning to the Levant from Babylon under the Achaemenid-appointed governor Zerubbabel. However, during the reign of Herod the Great, the Second Temple was completely refurbished, and the original structure was totally overhauled into the large and magnificent edifices and facades that are more recognizable. Much as the Babylonians destroyed the First Temple, the Romans destroyed the Second Temple and Jerusalem in 70 CE as retaliation for an ongoing Jewish revolt. The second temple lasted for a total of 585 years (516 BCE to 70 CE).[2][3]

Jewish eschatology includes a belief that the Second Temple will be replaced by a future Third Temple.

Biblical narrative[edit]

The accession of Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire in 559 BCE made the re-establishment of the city of Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Temple possible.[4][5] Some rudimentary ritual sacrifice had continued at the site of the first temple following its destruction.[6] According to the closing verses of the second book of Chronicles and the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, when the Jewish exiles returned to Jerusalem following a decree from Cyrus the Great (Ezra 1:1–4, 2 Chron 36:22–23), construction started at the original site of the altar of Solomon's Temple.[1] After a relatively brief halt due to opposition from peoples who had filled the vacuum during the Jewish captivity (Ezra 4), work resumed c. 521 BCE under Darius I (Ezra 5) and was completed during the sixth year of his reign (c. 516 BCE), with the temple dedication taking place the following year.[citation needed]

These events represent the final section in the historical narrative of the Hebrew Bible.[4]

The original core of the book of Nehemiah, the first-person memoir, may have been combined with the core of the Book of Ezra around 400 BCE. Further editing probably continued into the Hellenistic era.[7]

The book tells how Nehemiah, at the court of the king in Susa, is informed that Jerusalem is without walls and resolves to restore them. The king appoints him as governor of the province Yehud Medinata and he travels to Jerusalem. There he rebuilds the walls, despite the opposition of Israel's enemies, and reforms the community in conformity with the law of Moses. After 12 years in Jerusalem, he returns to Susa but subsequently revisits Jerusalem. He finds that the Israelites have been backsliding and taking non-Jewish wives, and he stays in Jerusalem to enforce the Law.

Based on the biblical account, after the return from Babylonian captivity, arrangements were immediately made to reorganize the desolated Yehud Province after the demise of the Kingdom of Judah seventy years earlier. The body of pilgrims, forming a band of 42,360,[8] having completed the long and dreary journey of some four months, from the banks of the Euphrates to Jerusalem, were animated in all their proceedings by a strong religious impulse, and therefore one of their first concerns was to restore their ancient house of worship by rebuilding their destroyed Temple[9] and reinstituting the sacrificial rituals known as the korbanot.

On the invitation of Zerubbabel, the governor, who showed them a remarkable example of liberality by contributing personally 1,000 golden darics, besides other gifts, the people poured their gifts into the sacred treasury with great enthusiasm.[10] First they erected and dedicated the altar of God on the exact spot where it had formerly stood, and they then cleared away the charred heaps of debris which occupied the site of the old temple; and in the second month of the second year (535 BCE), amid great public excitement and rejoicing, the foundations of the Second Temple were laid. A wide interest was felt in this great movement, although it was regarded with mixed feelings by the spectators (Haggai 2:3, Zechariah 4:10).[9]

The Samaritans wanted to help with this work but Zerubbabel and the elders declined such cooperation, feeling that the Jews must build the Temple unaided. Immediately evil reports were spread regarding the Jews. According to Ezra 4:5, the Samaritans sought to "frustrate their purpose" and sent messengers to Ecbatana and Susa, with the result that the work was suspended.[9]

Seven years later, Cyrus the Great, who allowed the Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple, died (2 Chronicles 36:22–23) and was succeeded by his son Cambyses. On his death, the "false Smerdis", an impostor, occupied the throne for some seven or eight months, and then Darius became king (522 BCE). In the second year of his rule the work of rebuilding the temple was resumed and carried forward to its completion (Ezra 5:6–6:15), under the stimulus of the earnest counsels and admonitions of the prophets Haggai and Zechariah. It was ready for consecration in the spring of 516 BCE, more than twenty years after the return from captivity. The Temple was completed on the third day of the month Adar, in the sixth year of the reign of Darius, amid great rejoicings on the part of all the people (Ezra 6:15,16), although it was evident that the Jews were no longer an independent people, but were subject to a foreign power. The Book of Haggai includes a prediction that the glory of the second temple would be greater than that of the first (Haggai 2:9).[9]

Some of the original artifacts from the Temple of Solomon are not mentioned in the sources after its destruction in 586 BCE, and are presumed lost. The Second Temple lacked the following holy articles:

- The Ark of the Covenant[5][9] containing the Tablets of Stone, before which were placed[11] the pot of manna and Aaron's rod[9]

- The Urim and Thummim[5][9] (divination objects contained in the Hoshen)

- The holy oil[9]

- The sacred fire.[5][9]

In the Second Temple, the Kodesh Hakodashim (Holy of Holies) was separated by curtains rather than a wall as in the First Temple. Still, as in the Tabernacle, the Second Temple included:

- The Menorah (golden lamp) for the Hekhal

- The Table of Showbread

- The golden altar of incense, with golden censers.[9]

According to the Mishnah,[12] the "Foundation Stone" stood where the Ark used to be, and the High Priest put his censer on it on Yom Kippur.[5]

The Second Temple also included many of the original vessels of gold that had been taken by the Babylonians but restored by Cyrus the Great.[9][13] According to the Babylonian Talmud[14] however, the Temple lacked the Shekhinah (the dwelling or settling divine presence of God) and the Ruach HaKodesh (holy spirit) present in the First Temple.

Rabbinical literature[edit]

Traditional rabbinic literature states that the Second Temple stood for 420 years and based on the 2nd-century work Seder Olam Rabbah, placed construction in 350 BCE (3408 AM), 166 years later than secular estimates, and destruction in 70 CE (3829 AM).[15]

The fifth order, or division, of the Mishnah, known as Kodashim, provides detailed descriptions and discussions of the religious laws connected with Temple service including the sacrifices, the Temple and its furnishings, as well as the priests who carried out the duties and ceremonies of its service. Tractates of the order deal with the sacrifices of animals, birds, and meal offerings, the laws of bringing a sacrifice, such as the sin offering and the guilt offering, and the laws of misappropriation of sacred property. In addition, the order contains a description of the Second Temple (tractate Middot), and a description and rules about the daily sacrifice service in the Temple (tractate Tamid).[16][17][18]

Rededication by the Maccabees[edit]

Following the conquest of Judea by Alexander the Great, it became part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt until 200 BCE, when the Seleucid king Antiochus III the Great of Syria defeated Pharaoh Ptolemy V Epiphanes at the Battle of Paneion.[19] Judea became at that moment part of the Seleucid Empire. When the Second Temple in Jerusalem was looted and its religious services stopped, Judaism was effectively outlawed.

In 167 BCE, Antiochus IV Epiphanes ordered an altar to Zeus erected in the Temple. He also banned circumcision and ordered pigs to be sacrificed at the altar of the Temple.[20]

Following the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid empire, the Second Temple was rededicated and became the religious pillar of the Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom, as well as culturally associated with the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah.

Hasmonean dynasty and Roman conquest[edit]

There is some evidence from archaeology that further changes to the structure of the Temple and its surroundings were made during the Hasmonean rule. Salome Alexandra, the queen of Hasmonean Kingdom appointed her elder son Hyrcanus II as the high priest of Judaea. Her younger son Aristobulus II was determined to have the throne, and as soon as she died he seized the throne. Hyrcanus, who was in line to be the king, agreed to be contented with being the high priest. Antipater, the governor of Idumæa, encouraged Hyrcanus not to give up his throne. Eventually Hyrcanus fled to Aretas III, king of the Nabateans, and returned with an army to take back the throne. He defeated Aristobulus and besieged Jerusalem. The Roman general Pompey, who was in Syria fighting against the Armenians in the Third Mithridatic War, sent his lieutenant to investigate the conflict in Judaea. Both Hyrcanus and Aristobulus appealed to him for support. Pompey was not diligent in making a decision about this which caused Aristobulus to march off. He was pursued by Pompey and surrendered but his followers closed Jerusalem to Pompey's forces. The Romans besieged and took the city in 63 BCE. The priests continued with the religious practices inside the Temple during the siege. The temple was not looted or harmed by the Romans. Pompey himself, perhaps inadvertently, went into the Holy of Holies and the next day ordered the priests to repurify the Temple and resume the religious practices.[21]

Herod's Temple[edit]

Reconstruction of the temple under Herod began with a massive expansion of the Temple Mount. Herod's work on the Temple is generally dated from 20/19 BCE until 12/11 or 10 BCE. Writer Bieke Mahieu dates the work on the Temple enclosures from 25 BCE and that on the Temple building in 19 BCE, and situates the dedication of both in November 18 BCE.[22] Religious worship and temple rituals continued during the construction process.[23] When the Roman emperor Caligula planned to place his own statue inside the temple, Herod's grandson Agrippa I was able to intervene and convince him against this.

Construction[edit]

Herod's Temple was one of the larger construction projects of the 1st century BCE.[24] Josephus records that Herod was interested in perpetuating his name through building projects, that his construction programs were extensive and paid for by heavy taxes, but that his masterpiece was the Temple of Jerusalem.[24]

The old temple built by Zerubbabel was replaced by a magnificent edifice. An agreement was made between Herod and the Jewish religious authorities: the sacrificial rituals, called offerings, were to be continued unabated for the entire time of construction, and the Temple itself would be constructed by the priests. Later the Exodus 30:13 sanctuary shekel was reinstituted to support the temple as the temple tax.

Platform[edit]

Mt. Moriah had a plateau at the northern end, and steeply declined on the southern slope. It was Herod's plan that the entire mountain be turned into a giant square platform. The Temple Mount was originally intended to be 1600 feet wide by 900 feet broad by 9 stories high, with walls up to 16 feet thick, but had never been finished. To complete it, a trench was dug around the mountain, and huge stone "bricks" were laid. Some of these weighed well over 100 tons, the largest measuring 44.6 feet by 11 feet by 16.5 feet and weighing approximately 567 to 628 tons,[25][26] while most were in the range of 2.5 by 3.5 by 15 feet (approximately 28 tons). King Herod had architects from Greece, Rome and Egypt plan the construction. The blocks were presumably quarried by using pickaxes to create channels. Then they hammered in wooden beams and flushed them with water to force them out. Once they were removed, they were carved into precise squares and numbered at the quarry to show where they would be installed. The final carving would have been done by using harder stones to grind or chisel them to create precise joints. They would have been transported using oxen and specialized carts. Since the quarry was uphill from the temple they had gravity on their side but care needed to be taken to control the descent. Final installation would have been done using pulleys or cranes. Roman pulleys and cranes weren't strong enough to lift the blocks alone so they may have used multiple cranes and levers to position them.[27] As the mountainside began to rise, the western side was carved away to a vertical wall and bricks were carved to create a virtual continuation of the brick face, which was continued for a while until the northern slope reached ground level. Part of the Antonian hill to the north of Moriah was annexed to the complex and the area between was filled up with landfill.

The project began with the building of giant underground vaults upon which the temple would be built so it could be larger than the small flat area on top of Mount Moriah. Ground level at the time was at least 20 ft. (6m) below the current level, as can be seen by walking the Western Wall tunnels. Legend has it that the construction of the entire complex lasted only three years, but other sources such as Josephus say that it took far longer, although the Temple itself may have taken that long. During a Passover visit by Jesus the Jews replied that it had been under construction for 46 years.[28] It is possible that the complex was only a few years completed when the future Emperor Titus destroyed the Temple in 70 CE.

Court of the Gentiles[edit]

This area was primarily a bazaar, with vendors selling souvenirs, sacrificial animals, food, as well as currency changers, exchanging Roman for Tyrian money because the Jews were not allowed to coin their own money and they viewed Roman currency as an abomination to the Lord,[29] as also mentioned in the New Testament account of Jesus and the Money Changers when Jerusalem was packed with Jews who had come for Passover, perhaps numbering 300,000 to 400,000 pilgrims.[30][31] Guides that provided tours of the premises were also available. Jewish males had the unique opportunity to be shown inside the temple itself.

The priests, in their white linen robes and tubular hats, were everywhere, directing pilgrims and advising them on what kinds of sacrifices were to be performed.

Behind them, as they entered the Court of the Gentiles from the south through the Huldah Gates, was the Royal Porch, which contained a marketplace, administrative quarters, and a synagogue. On the upper floors, the great Jewish sages held court, priests and Levites performed various chores, and from there, tourists were able to observe the events. The Royal Porch is widely accepted to be part of Herod's work; however, recent archaeological finds in the Western Wall tunnels suggest that it was built in the first century during the reign of Agripas, as opposed to the first century BCE,[32] while the theory that Herod began the extension and the Royal Porch is based mainly on Josephus's possibly politically motivated claim. During Herod's reign the porch was not yet open to the public.

To the east of the court was Solomon's Porch, and to the north, the soreg, the "middle wall of separation",[33] a stone wall separating the public area from the inner sanctuary where only Jews could enter, described as being 3 cubits high by Josephus (Wars 5.5.2 [3b] 6.2.4).

Pinnacle[edit]

The accounts of the temptation of Christ in the gospels of Matthew and Luke both suggest that the Second Temple had one or more 'pinnacles':

Then he [Satan] brought Him to Jerusalem, set Him on the pinnacle of the temple, and said to Him, "If You are the Son of God, throw Yourself down from here."[34]

The Greek word used is πτερυγιον (pterugion), which literally means a tower, rampart, or pinnacle.[35] According to Strong's Concordance, it can mean little wing, or by extension anything like a wing such as a battlement or parapet.[36] The archaeologist Benjamin Mazar thought it referred to the southeast corner of the Temple overlooking the Kidron Valley.[37]

Inside the Soreg[edit]

According to Josephus, there were ten entrances into the inner courts, four on the south, four on the north, one on the east and one leading east to west from the Court of Women to the court of the Israelites, named the Nicanor Gate.[38] The gates were: On the south side (going from west to east) the Fuel Gate, the Firstling Gate, the Water Gate. On the north side, from west to east, are the Jeconiah Gate, the Offering Gate, the Women's Gate and the Song Gate. On the Eastern side, the Nicanor gate, which is where most Jewish visitors entered. A few pieces of the Soreg have survived to the present day.

Within this area was the Court of the Women, open to all Jews, male and female. Even a ritually unclean Cohen could enter to perform various housekeeping duties. There was also a place for lepers (considered ritually unclean), as well as a ritual barbershop for Nazirites. In this, the largest of the temple courts, one could see constant dancing, singing and music.

Only men were allowed to enter the Court of the Israelites, where they could observe sacrifices of the high priest in the Court of the Priests. The Court of the Priests was reserved for Levite priests.

Temple sanctuary[edit]

Between the entrance of the building and the curtain veiling the Holy of Holies were the famous vessels of the temple: the menorah, the incense-burning altar, and various other implements.

Pilgrimages[edit]

Jews from distant parts of the Roman Empire would arrive by boat at the port of Jaffa (now part of Tel Aviv), where they would join a caravan for the three-day trek to the Holy City and would then find lodgings in one of the many hotels or hostelries. Then they changed some of their money from the profane standard Greek and Roman currency for Jewish and Tyrian money, the latter two considered religious.[39][40] The pilgrims would purchase sacrificial animals, usually a pigeon or a lamb, in preparation for the following day's events.

The first thing pilgrims would do would be to approach the public entrance on the south side of the Temple Mount complex. They would check their animals, then visit a mikveh, where they would ritually cleanse and purify themselves. The pilgrims would then retrieve their sacrificial animals, and head to the Huldah gates. After ascending a staircase three stories in height, and passing through the gate, the pilgrims would find themselves in the Court of the Gentiles.

Destruction[edit]

In 66 CE the Jewish population rebelled against the Roman Empire. Four years later, on 4 August 70 CE[41] (the 9th Day of Av and possibly the day on which Tisha B'Av was observed[42]) or 30 August 70 CE,[43] Roman legions under Titus retook and destroyed much of Jerusalem and the Second Temple. The Arch of Titus, in Rome and built to commemorate Titus's victory in Judea, depicts a Roman victory procession with soldiers carrying spoils from the Temple, including the Menorah. According to an inscription on the Colosseum, Emperor Vespasian built the Colosseum with war spoils in 79 CE—possibly from the spoils of the Second Temple.[44]

The sects of Judaism that had their base in the Temple dwindled in importance, including the priesthood and the Sadducees.[45]

The Temple was on the site of what today is the Dome of the Rock. The gates let out close to Al-Aqsa Mosque (which came much later).[23] Although Jews continued to inhabit the destroyed city, Emperor Hadrian established a new city called Aelia Capitolina. At the end of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE, many of the Jewish communities were massacred and Jews were banned from living inside Jerusalem. A pagan Roman temple was set up on the former site of Herod's Temple.[21]

Archaeology[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In 1871, a hewn stone measuring 60 × 90 cm. and engraved with Greek uncials was discovered near a court on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and identified by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau as being the Temple Warning inscription. The stone inscription outlined the prohibition extended unto those who were not of the Jewish nation to proceed beyond the soreg separating the larger Court of the Gentiles and the inner courts. The inscription read in seven lines:

ΜΗΟΕΝΑΑΛΛΟΓΕΝΗΕΙΣΠΟ

ΡΕΥΕΣΟΑΙΕΝΤΟΣΤΟΥΠΕ

ΡΙΤΟΙΕΡΟΝΤΡΥΦΑΚΤΟΥΚΑΙ

ΠΕΡΙΒΟΛΟΥΟΣΔΑΝΛΗ

ΦΘΗΕΑΥΤΩΙΑΙΤΙΟΣΕΣ

ΤΑΙΔΙΑΤΟΕΞΑΚΟΛΟΥ

ΘΕΙΝΘΑΝΑΤΟΝ

Translation: "Let no foreigner enter within the parapet and the partition which surrounds the Temple precincts. Anyone caught [violating] will be held accountable for his ensuing death." Today, the stone is preserved in Istanbul's Museum of Antiquities.

In 1936 a fragment of a similar Temple warning inscription was found.

After 1967, archaeologists found that the wall extended all the way around the Temple Mount and is part of the city wall near the Lions' Gate. Thus, the Western Wall is not the only remaining part of the Temple Mount. Currently, Robinson's Arch (named after American Edward Robinson) remains as the beginning of an arch that spanned the gap between the top of the platform and the higher ground farther away. This had been used by the priests as an entrance. Commoners had entered through the still-extant, but now plugged, gates on the southern side which led through colonnades to the top of the platform. One of these colonnades is still extant and reachable through the Temple Mount. The Southern wall was designed as a grand entrance. Recent archeological digs have found thousands of mikvehs (ceremonial bathtubs) for the ritual purification of the worshipers, and a grand stairway leading to the now blocked entrance. Inside the walls, the platform was supported by a series of vaulted archways, now called Solomon's Stables, which still exist and whose current renovation by the Waqf is extremely controversial. The temple was constructed of imported white marble that gleamed in the daylight.

On September 25, 2007, Yuval Baruch, archaeologist with the Israeli Antiquities Authority announced the discovery of a quarry compound which may have provided King Herod with the stones to build his Temple on the Temple Mount. Coins, pottery and an iron stake found proved the date of the quarrying to be about 19 BCE. Archaeologist Ehud Netzer confirmed that the large outlines of the stone cuts is evidence that it was a massive public project worked by hundreds of slaves.[46] More recent archaeological findings include mosaic floors from the Second Temple period.[47]

The Magdala stone is thought to be a representation of the Second Temple carved before its destruction in the year 70.[48]

Gallery[edit]

The Trumpeting Place inscription, a stone (2.43 × 1 m) with Hebrew inscription "To the Trumpeting Place" excavated by Benjamin Mazar at the southern foot of the Temple Mount is believed to be a part of the Second Temple.

Second Temple Judaism[edit]

The period between the construction of the Second Temple in 515 BCE and its destruction by the Romans in 70 CE witnessed major historical upheavals and significant religious changes that would affect most subsequent Abrahamic religions. The origins of the authority of scripture, of the centrality of law and morality in religion, of the synagogue and of apocalyptic expectations for the future all developed in the Judaism of this period.

See also[edit]

- Archaeological remnants of the Jerusalem Temple

- Herodian architecture

- Jerusalem stone

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

- List of megalithic sites

- Replicas of the Jewish Temple

- Temple of Peace, Rome

- Timeline of Jewish history

References[edit]

- ^ a b Understanding Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism, KTAV Publishing House, Lawrence H. Schiffman, page 48–49

- ^ Ezra 6:15,16

- ^ Based on regnal years of Darius I, brought down in Richard Parker & Waldo Dubberstein's Babylonian Chronology, 626 B.C.–A.D. 75, Brown University Press: Providence 1956, p. 30. However, Jewish tradition avers that the Second Temple stood for only 420 years, i.e. from 352 BCE – 68 CE. See: Maimonides' Questions & Responsa, responsum # 389, Jerusalem 1960 (Hebrew)

- ^ a b Albright, William (1963). The Biblical Period from Abraham to Ezra: An Historical Survey. HarperCollins College Division. ISBN 0-06-130102-7.

- ^ a b c d e

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Temple, The Second". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Temple, The Second". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ The Hebrew Bible: New Insights and Scholarship, New York University Press, chapter by Ziony Zevit, page 166

- ^ Paul Cartledge, Peter Garnsey, Erich S. Gruen (editors), Hellenistic Constructs: Essays In Culture, History, and Historiography, p. 92 (University of California Press, 1997). ISBN 0-520-20676-2

- ^ Ezra 2:65

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k

Easton, Matthew George (1897). . Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

Easton, Matthew George (1897). . Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

- ^ Ezra 2

- ^ Maimonides. "Mishneh Torah, Sefer Avodah, Beis Habechirah, Chapter 4, Halacha 1". Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ^ Middot 3:6

- ^ Ezra 1:7–11

- ^ Yoma 21b

- ^ Goldwurm, Hersh. History of the Jewish people: the Second Temple era, Mesorah Publications, 1982. Appendix: Year of the Destruction, p. 213. ISBN 0-89906-454-X

- ^ Birnbaum, Philip (1975). "Kodashim". A Book of Jewish Concepts. New York, NY: Hebrew Publishing Company. pp. 541–542. ISBN 088482876X.

- ^ Epstein, Isidore, ed. (1948). "Introduction to Seder Kodashim". The Babylonian Talmud. vol. 5. Singer, M.H. (translator). London: The Soncino Press. pp. xvii–xxi.

- ^ Arzi, Abraham (1978). "Kodashim". Encyclopedia Judaica. 10 (1st ed.). Jerusalem, Israel: Keter Publishing House Ltd. pp. 1126–1127.

- ^ De Bellis Antiquitatis (DBA) The Battle of Panion (200 BC) Archived 2009-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Flavius Josephus, The Wars of the Jews Jewish War i. 34

- ^ a b Lester L. Grabbe (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus. A&C Black. pp. 19–20, 26–29. ISBN 9780567552488.

- ^ Mahieu, B., Between Rome and Jerusalem, OLA 208, Leuven: Peeters, 2012, pp. 147–165)

- ^ a b Secrets of Jerusalem's Temple Mount, Leen and Kathleen Ritmeyer, 1998

- ^ a b Flavius Josephus: The Jewish War

- ^ The History Channel cited the 16.5 depth 567 ton estimate in "Lost Worlds of King Herod"

- ^ Dan Bahat: Touching the Stones of our Heritage, Israeli ministry of Religious Affairs, 2002

- ^ Modern Marvels: Bible tech, History channel

- ^ Gospel of John 2:20

- ^ Beasley-Murray, G. (1999). Word Biblical Commentary: John (2 ed., Vol. 36). Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993. p. 249

- ^ Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998.

- ^ "Israel Antiquities Authority".

- ^ In verse 14 of Ephesians 2:11–18

- ^ Luke 4:9

- ^ Kittel, Gerhard, ed. (1976) [1965]. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament: Volume III. Translated by Bromiley, Geoffrey W. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 236.

- ^ Strong's Concordance 4419

- ^ Mazar, Benjamin (1975). The Mountain of the Lord, Doubleday. p. 149.

- ^ Josephus, War 5.5.2; 198; m. Mid. 1.4

- ^ Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D.. Jesus, Interrupted, HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 0-06-117393-2

- ^ "Hebrew Calendar". www.cgsf.org.

- ^ Tisha B'Av is a day of mourning, which is considered inappropriate for the joyful atmosphere of the Sabbath. Thus, if its date falls on a Sabbath, it is observed on the 10th of Av instead. If this modern Jewish practice was followed in the Second Temple period, Tisha B'Av would have fallen on Sunday August 5 in 70 CE. Josephus gives the date of 10 Loos for the destruction, in a lunar calendar almost identical to the Hebrew calendar.

- ^ Matthew Bunson A Dictionary of the Roman Empire p.212

- ^ Bruce Johnston. "Colosseum 'built with loot from sack of Jerusalem temple'". Telegraph.

- ^ Alföldy, Géza (1995). "Eine Bauinschrift aus dem Colosseum". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 109: 195–226. JSTOR 20189648.

- ^ Gaffney, Sean (2007-09-24). "USATODAY.com, Report: Herod's Temple quarry found". USA Today. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ^ "Second Temple Flooring restored". Haaretz. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Kershner, Isabel (8 December 2015). "A Carved Stone Block Upends Assumptions About Ancient Judaism". New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

Further reading[edit]

- Grabbe, Lester. 2008. A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. 2 vols. New York: T&T Clark.

- Nickelsburg, George. 2005. Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishnah: A Historical and Literary Introduction. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Schiffman, Lawrence, ed. 1998. Texts and Traditions: A Source Reader for the Study of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. Hoboken, NJ: KTAV.

- Stone, Michael, ed. 1984. The Literature of the Jewish People in the Period of the Second Temple and the Talmud. 2 vols. Philadelphia: Fortress.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Second Jewish temple in Jerusalem. |

| Library resources about Second Temple |

- Resources > Second Temple and Talmudic Era > Second Temple Jerusalem The Jewish History Resource Center, Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Temple, The Second

- 4 Enoch: The Online Encyclopedia of Second Temple Judaism

- Second Temple of Jerusalem (renders album of 3d model) / Zonerama photo gallery

- Jerusalem Videos The Southern & Western walls in Jerusalem – The Temple Mount

- Resources > Second Temple and Talmudic Era > Second Temple Jerusalem The Jewish History Resource Center, Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Temple Mount Photos The Temple Mount photos including sites below the Mount itself, off limits to any non-Muslims

- Resources > Second Temple and Talmudic Era > Herod and the Herodian Dynasty The Jewish History Resource Center – Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Temple of Herod

- PBS Frontline: Temple Culture

- Picture gallery of a model of the temple

- Resources > Second Temple and Talmudic Era > Second Temple Jerusalem The Jewish History Resource Center, Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Temple, The Second

- 4 Enoch: The Online Encyclopedia of Second Temple Judaism

- Second Temple

- 1st-century BC religious buildings and structures

- 1st-century disestablishments

- 6th-century BC establishments

- 6th-century BC religious buildings and structures

- 515 BC

- 70 disestablishments

- 70s disestablishments in the Roman Empire

- Buildings and structures demolished in the 1st century

- 1871 archaeological discoveries

- Religion in ancient Israel and Judah

- Ancient Jewish Greek history

- Jews and Judaism in the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire

- Ancient Jewish Persian history

- Ancient Hebrew pilgrimage sites

- Classical sites in Jerusalem

- Destroyed temples

- Ezra–Nehemiah

- Herod the Great

- Jewish Persian and Iranian history

- Tabernacle and Temples in Jerusalem

- Cyrus the Great

- Darius I

- History of Hanukkah