Return of the Jedi

| Return of the Jedi | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Kazuhiko Sano | |

| Directed by | Richard Marquand |

| Produced by | Howard Kazanjian |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | George Lucas |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Williams |

| Cinematography | Alan Hume |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 132 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $32.5 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $475.3 million[4][5] |

Return of the Jedi (also known as Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi) is a 1983 American epic space opera film directed by Richard Marquand. The screenplay is by Lawrence Kasdan and George Lucas from a story by Lucas, who was also the executive producer. It is the third installment in the original Star Wars trilogy, the third film to be produced, the sixth film in the "Star Wars saga" and the first film to use THX technology. It takes place one year after The Empire Strikes Back.[6] The film stars Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Billy Dee Williams, Anthony Daniels, David Prowse, Kenny Baker, Peter Mayhew and Frank Oz.

In the film, the Galactic Empire, under the direction of the ruthless Emperor, is constructing a second Death Star in order to crush the Rebel Alliance once and for all. Since the Emperor plans to personally oversee the final stages of its construction, the Rebel Fleet launches a full-scale attack on the Death Star in order to prevent its completion and kill the Emperor, effectively bringing an end to his hold over the galaxy. Meanwhile, Luke Skywalker, now a Jedi Knight, struggles to bring his father Darth Vader back to the light side of the Force.

Steven Spielberg, David Lynch and David Cronenberg were considered to direct the project before Marquand signed on as director. The production team relied on Lucas' storyboards during pre-production. While writing the shooting script, Lucas, Kasdan, Marquand, and producer Howard Kazanjian spent two weeks in conference discussing ideas to construct it. Kazanjian's schedule pushed shooting to begin a few weeks early to allow Industrial Light & Magic more time to work on the film's effects in post-production. Filming took place in England, California, and Arizona from January to May 1982. Strict secrecy surrounded the production.

The film was released in theaters on May 25, 1983, six years to the day of the release of the first film, receiving mostly positive reviews. It grossed $374 million during its initial theatrical run, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1983. Several re-releases and revisions to the film have followed over the decades, which has also brought its total gross to $475 million.

Plot[edit]

C-3PO and R2-D2 are sent to crime lord Jabba the Hutt's palace on Tatooine in a trade bargain made by Luke Skywalker to rescue Han Solo. Disguised as a bounty hunter, Princess Leia infiltrates the palace under the pretense of collecting the bounty on Chewbacca and unfreezes Han, but is caught and enslaved. Luke soon arrives to bargain for his friends' release, but Jabba drops him through a trapdoor to be executed by a rancor. After Luke kills the rancor, Jabba sentences him, Han, and Chewbacca to death by being fed to the Sarlacc, a huge, carnivorous plant-like desert beast. Having hidden his new lightsaber inside R2-D2, Luke frees himself and battles Jabba's guards while Leia uses her chains to strangle Jabba to death. As the others rendezvous with the Rebel Alliance, Luke returns to Dagobah to complete his training with Yoda, whom he finds is dying. Yoda confirms that Darth Vader, once known as Anakin Skywalker, is Luke's father, and becomes one with the Force. The Force ghost of Obi-Wan Kenobi reveals that Leia is Luke's twin sister, and tells Luke that he must face Vader again to finish his training and defeat the Empire.

The Rebel Alliance learns that the Empire has been constructing a second Death Star under the supervision of the Emperor himself. As the station is protected by an energy shield, Han leads a strike team to destroy the shield generator on the forest moon of Endor; doing so would allow a squadron of starfighters to destroy the Death Star. Luke and Leia accompany the strike team to Endor in a stolen Imperial shuttle. Luke and his companions encounter a tribe of Ewoks and, after an initial conflict, gain their trust. Later, Luke tells Leia that she is his sister, Vader is their father, and that he must confront him. Surrendering to Imperial troops, he is brought before Vader, and tries to convince his father to reject the dark side of the Force, to no avail.

Vader takes Luke to the Death Star to meet the Emperor, intending to turn him to the dark side. The Emperor reveals that the Imperial forces are prepared for a Rebel assault on the shield generator and that the Rebel Fleet will fall into a trap. On the forest moon of Endor, Han's team is captured by Imperial forces, but a counterattack by the Ewoks allow the Rebels to infiltrate the shield generator. Meanwhile, Lando Calrissian in the Millennium Falcon and Admiral Ackbar lead the rebel assault on the second Death Star only to find that the Death Star's shield is still active, and the Imperial fleet waits for them.

The Emperor reveals to Luke that the Death Star is fully operational and orders the firing of its massive superlaser, destroying one of the Rebel starships. The Emperor tempts Luke to give in to his anger. Luke attacks him, but Vader intervenes and the two engage in another lightsaber duel. Vader senses that Luke has a sister and threatens to turn her to the dark side. Enraged, Luke severs Vader's prosthetic hand. The Emperor entreats Luke to kill Vader and take his place, but Luke refuses, declaring himself a Jedi like his father before him. Furious, the Emperor tortures Luke with Force lightning. Unwilling to let his son die, Vader throws the Emperor down a reactor shaft to his death but is mortally electrocuted in the process. At his father's last request, Luke removes Vader's mask, and the redeemed Anakin Skywalker dies in his son's arms.

After the strike team destroys the shield generator, Lando leads a group of Rebel fighters into the Death Star's core. While the Rebel fleet destroys the Super Star Destroyer Executor, Lando and X-wing fighter pilot Wedge Antilles destroy the Death Star's main reactor. As the Falcon escapes the Death Star's superstructure and Luke escapes on a shuttle with his father's body, the station explodes. On the Forest Moon of Endor, Leia reveals to Han that Luke is her brother, and she and Han kiss. Luke cremates his father's body on a pyre before reuniting with his friends. As the Rebels and the galaxy celebrate the fall of the Empire, Luke sees the spirits of Yoda, Obi-Wan, and Anakin watching over him.

Cast[edit]

- Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker, one of the last living Jedi knights, trained by Obi-Wan and Yoda; Leia's twin brother, Han's friend and Darth Vader's son who is also a skilled X-wing fighter pilot allied with the Rebellion.

- Harrison Ford as Han Solo, a rogue smuggler aiding the Rebellion against the Empire, Luke’s friend, and Leia's love interest.

- Carrie Fisher as Leia Organa, the former princess of the destroyed planet Alderaan, who is part of the Rebellion, Luke's twin sister, and Han's love interest.

- Billy Dee Williams as Lando Calrissian, the former Baron Administrator of Cloud City and one of Han's friends who aids the Rebellion.

- Anthony Daniels as C-3PO, a humanoid protocol droid in the service of the Rebellion.

- Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca, a Wookiee who is Han's longtime friend and part of the Rebellion.

- Kenny Baker as

- R2-D2, an astromech droid, friend of Luke, and longtime companion of C-3PO.

- Paploo, an Ewok who distracts Scout troopers by hijacking a speeder bike.

- Ian McDiarmid as The Emperor, the evil founding supreme ruler of the Galactic Empire and Vader's Sith master.

- Frank Oz as Yoda, the wise, centuries-old Jedi Master, who lives on Dagobah and trained Luke.

- David Prowse as Darth Vader, a powerful Sith lord and the second in command of the Galactic Empire; Luke and Leia's father.

- James Earl Jones as the voice of Darth Vader

- Sebastian Shaw as Anakin Skywalker. After defeating the Emperor, Vader asks Luke to take off his mask so he can see his son clearly before he dies. Originally, Shaw also appeared as Anakin's Force ghost.

- Hayden Christensen as Anakin's Force ghost. In the 2004 DVD release of the original trilogy, the actor who portrayed Anakin in the second and third prequel films replaces Shaw as the character's Force ghost; this change was intended to bring Return of the Jedi into continuity with the larger saga.[7]

- Alec Guinness as Obi-Wan Kenobi, a deceased Jedi Master, who continues to teach Luke after death as a Force ghost.

Denis Lawson reprises his role as Wedge Antilles and Kenneth Colley and Jeremy Bulloch reprise their roles as Admiral Piett and Boba Fett from The Empire Strikes Back respectively. Michael Pennington portrays Moff Jerjerrod, the commander of the second Death Star. Warwick Davis appears as Wicket W. Warrick, an Ewok who leads Leia and eventually her friends to the Ewok tribe. Baker was originally cast as Wicket, but was replaced by Davis after falling ill with food poisoning on the morning of the shoot. Davis had no previous acting experience and was cast only after his grandmother had discovered an open call for dwarfs for the new Star Wars film.[8] Caroline Blakiston portrays Mon Mothma, a co-founder and leader of the Rebel Alliance. Michael Carter played Jabba's aide, Bib Fortuna (voiced by Erik Bauersfeld), while Femi Taylor and Claire Davenport appeared as Jabba's original slave dancers.

To portray the numerous alien species featured in the film a multitude of puppeteers, voice actors, and stunt performers were employed. Admiral Ackbar was performed by puppeteer Tim Rose, with his voice provided by Erik Bauersfeld. Nien Nunb was portrayed by Richard Bonehill in costume for full body shots, while he was otherwise a puppet operated by Mike Quinn and his voice was provided by Kipsang Rotich. Rose also operated Salacious Crumb, whose voice was provided by Mark Dodson. Quinn also played Ree-Yees and Wol Cabbashite. Sy Snootles was a marionette operated by Rose and Quinn, while her voice was provided by Annie Arbogast. Others included Simon J. Williamson as Max Rebo, a Gamorrean Guard and a Mon Calamari; Deep Roy as Droopy McCool; Ailsa Berk as Amanaman; Paul Springer as Ree-Yees, Gamorrean Guard and a Mon Calamari; Hugh Spight as a Gamorrean Guard, Elom and a Mon Calamari; Swee Lim as Attark the Hoover; Richard Robinson as a Yuzzum; Gerald Home as Tessek and the Mon Calamari officer; Phil Herbert as Hermi Odle; Tik and Tok (Tim Dry and Sean Crawford) as Whiphid and Yak-Face; Phil Tippett as the Rancor with Michael McCormick.

Jabba the Hutt was operated by Toby Philpott, David Barclay and Mike Edmonds (who also portrays the Ewok Logray) operated the tail. Larry Ward portrays the Huttese language voice with Quinn, among other roles, controlling the eyes.

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

As with the previous film, Lucas personally financed Return of the Jedi. Lucas also chose not to direct Return of the Jedi himself, and started searching for a director.[8] Although Lucas' first choice was Steven Spielberg, their separate feuds with the Director's Guild led to his being banned from directing the film.[9] Lucas approached David Lynch, who had been nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director for The Elephant Man in 1980, to helm Return of the Jedi, but Lynch declined, saying that he had "next door to zero interest".[10] David Cronenberg was also offered the chance to direct, but he declined the offer to make Videodrome and The Dead Zone.[11] Lamont Johnson, director of Spacehunter: Adventures in the Forbidden Zone, was also considered.[12] Lucas eventually chose Richard Marquand. Lucas may have directed some of the second unit work personally as the shooting threatened to go over schedule; this is a function Lucas had willingly performed on previous occasions when he had only officially been producing a film (e.g. More American Graffiti, Raiders of the Lost Ark). Lucas did operate the B camera on the set a few times.[13] Lucas himself has admitted to being on the set frequently because of Marquand's relative inexperience with special effects.[8] Lucas praised Marquand as a "very nice person who worked well with actors".[14] Marquand did note that Lucas kept a conspicuous presence on set, joking, "It is rather like trying to direct King Lear – with Shakespeare in the next room!"[15]

The screenplay was written by Lawrence Kasdan and Lucas (with uncredited contributions by David Peoples and Marquand), based on Lucas' story. Kasdan claims he told Lucas that Return of the Jedi was "a weak title", and Lucas later decided to name the film Revenge of the Jedi.[8] The screenplay itself was not finished until rather late in pre-production, well after a production schedule and budget had been created by Kazanjian and Marquand had been hired, which was unusual for a film. Instead, the production team relied on Lucas' story and rough draft in order to commence work with the art department. When it came time to formally write a shooting script, Lucas, Kasdan, Marquand and Kazanjian spent two weeks in conference discussing ideas; Kasdan used tape transcripts of these meetings to then construct the script.[16]

The issue of whether Harrison Ford would return for the final film arose during pre-production. Unlike the other stars of the first film, Ford had not contracted to do two sequels, and Raiders of the Lost Ark had made him an even bigger star. Return of the Jedi producer Howard Kazanjian (who also produced Raiders of the Lost Ark) convinced Ford to return:

I played a very important part in bringing Harrison back for Return of the Jedi. Harrison, unlike Carrie Fisher and Mark Hamill signed only a two picture contract. That is why he was frozen in carbonite in The Empire Strikes Back. When I suggested to George we should bring him back, I distinctly remember him saying that Harrison would never return. I said what if I convinced him to return. George simply replied that we would then write him in to Jedi. I had just recently negotiated his deal for Raiders of the Lost Ark with Phil Gersh of the Gersh Agency. I called Phil who said he would speak with Harrison. When I called back again, Phil was on vacation. David, his son, took the call and we negotiated Harrison's deal. When Phil returned to the office several weeks later he called me back and said I had taken advantage of his son in the negotiations. I had not. But agents are agents.[17]

Ford suggested that Han Solo be killed through self-sacrifice. Kasdan concurred, saying it should happen near the beginning of the third act to instill doubt as to whether the others would survive, but Lucas was vehemently against it and rejected the concept.[8] Gary Kurtz, who produced Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back but was replaced as producer for Return of the Jedi by Kazanjian, said in 2010 that the ongoing success with Star Wars merchandise and toys led George Lucas to reject the idea of killing off Han Solo in the middle part of the film during a raid on an Imperial base. Luke Skywalker was also to have walked off alone and exhausted like the hero in a Spaghetti Western but, according to Kurtz, Lucas opted for a happier ending to encourage higher merchandise sales.[18] Harrison Ford himself has confirmed this account, saying that Lucas "didn't see any future in dead Han toys."[19]

Yoda was originally not meant to appear in the film, but Marquand strongly felt that returning to Dagobah was essential to resolve the dilemma raised by the previous film.[16] The inclusion led Lucas to insert a scene in which Yoda confirms that Darth Vader is Luke's father because, after a discussion with a children's psychologist, he did not want younger moviegoers to dismiss Vader's claim as a lie.[14] Many ideas from the original script were left out or changed. For instance, the Ewoks were going to be Wookiees[20] and the Millennium Falcon would be used in the arrival at the forest moon of Endor. Following the defeat of the Emperor, the film was originally intended to end with Obi-Wan Kenobi and Yoda returning to life from their spectral existence in the Force, along with Anakin Skywalker, thanks to Yoda being able to prevent him from becoming one with the Force. They would then join the rest of the characters in their celebration on Endor.[21]

Filming[edit]

Filming began on January 11, 1982, and lasted through May 20, 1982, a schedule six weeks shorter than The Empire Strikes Back. Kazanjian's schedule pushed shooting as early as possible in order to give Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) as much time as possible to work on effects, and left some crew members dubious of their ability to be fully prepared for the shoot.[23] Working on a budget of $32.5 million,[24] Lucas was determined to avoid going over budget as had happened with The Empire Strikes Back. Producer Howard Kazanjian estimated that using ILM (owned wholly by Lucasfilm) for special effects saved the production approximately $18 million.[24] However, the fact that Lucasfilm was a non-union company made acquiring shooting locations more difficult and more expensive, even though Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back had been big hits.[8] The project was given the working title Blue Harvest with a tagline of "Horror Beyond Imagination." This disguised what the production crew was really filming from fans and the press, and also prevented price gouging by service providers.[8]

The first stage of production started with 78 days at Elstree Studios in England,[23] where the film occupied all nine stages. The shoot commenced with a scene later deleted from the finished film where the heroes get caught in a sandstorm as they leave Tatooine.[15] (This was the only major sequence cut from the film during editing.)[16] While attempting to film Luke Skywalker's battle with the rancor beast, Lucas insisted on trying to create the scene in the same style as Toho's Godzilla films by using a stunt performer inside a suit. The production team made several attempts, but were unable to create an adequate result. Lucas eventually relented and decided to film the rancor as a high-speed puppet.[8] In April, the crew moved to the Yuma Desert in Arizona for two weeks of Tatooine exteriors.[15] Production then moved to the redwood forests of northern California[25] near Crescent City where two weeks were spent shooting the Endor forest exteriors, and then concluded at ILM in San Rafael, California for about ten days of bluescreen shots. One of two "skeletal" post-production units shooting background matte plates spent a day in Death Valley.[23] The other was a special Steadicam unit shooting forest backgrounds from June 15–17, 1982, for the speeder chase near the middle of the film.[26] Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown personally operated these shots as he walked through a disguised path inside the forest shooting at less than one frame per second. By walking at about 5 mph (8 km/h) and projecting the footage at 24 frame/s, the motion seen in the film appeared as if it were moving at around 120 mph (190 km/h).[8]

Harrison Ford altered some scenes during the shoot, causing Billy Dee Williams to forget some of his lines, which was a source of frustration for Marquand. Marquand and Anthony Daniels also clashed somewhat, leading to the latter recording his ADR with Lucas instead.[27]

Music[edit]

John Williams composed and conducted the film's musical score with performances by the London Symphony Orchestra. Orchestration credits also include Thomas Newman.[28] The initial release of the film's soundtrack was on the RSO Records label in the United States. Sony Classical Records acquired the rights to the classic trilogy scores in 2004 after gaining the rights to release the second trilogy soundtracks (The Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones). In the same year, Sony Classical re-pressed the 1997 RCA Victor release of Return of the Jedi along with the other two films in the trilogy. The set was released with the new artwork mirroring the first DVD release of the film. Despite the Sony digital re-mastering, which minimally improved the sound heard only on high-end stereos, this 2004 release is essentially the same as the 1997 RCA Victor release.[29]

Post-production[edit]

Meanwhile, special effects work at ILM quickly stretched the company to its operational limits. While the R&D work and experience gained from the previous two films in the trilogy allowed for increased efficiency, this was offset by the desire to have the closing film raise the bar set by each of these films.[24] A compounding factor was the intention of several departments of ILM to either take on other film work or decrease staff during slow cycles. Instead, as soon as production began, the entire company found it necessary to remain running 20 hours a day on six-day weeks in order to meet their goals by April 1, 1983. Of about 900 special effects shots,[23] all VistaVision optical effects remained in-house, since ILM was the only company capable of using the format, while about 400 4-perf opticals were subcontracted to outside effects houses.[30] Progress on the opticals was severely delayed for a time when ILM rejected about 30,000 metres (100,000 ft) of film when the film perforations failed image registration and steadiness tests.[23]

Release[edit]

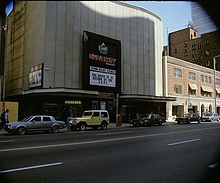

Return of the Jedi's theatrical release took place on May 25, 1983. It was originally slated to be May 27, but was subsequently changed to coincide with the date of the 1977 release of the original Star Wars film.[24] With a massive worldwide marketing campaign, illustrator Tim Reamer created the image for the movie poster and other advertising. At the time of its release, the film was advertised on posters and merchandise as simply Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, despite its on-screen "Episode VI" distinction. The original film was later re-released to theaters in 1985.

In 1997, for the 20th anniversary of the release of Star Wars (re-titled Episode IV: A New Hope), Lucas released the Star Wars Trilogy: Special Edition. Along with the two other films in the original trilogy, Return of the Jedi was re-released on March 7, 1997, with a number of changes and additions, which included the insertion of several alien band members and a different song in Jabba's throne room, the modification of the Sarlacc to include a beak, the replacement of music at the closing scene, and a montage of different alien worlds celebrating the fall of the Empire.[31]

Title change[edit]

The original teaser trailer for the film carried the name Revenge of the Jedi.[32] In December 1982, Lucas decided that "Revenge" was not appropriate as Jedi should not seek revenge and returned to his original title. By that time thousands of "Revenge" teaser posters (with artwork by Drew Struzan) had been printed and distributed. Lucasfilm stopped the shipping of the posters and sold the remaining stock of 6,800 posters to Star Wars fan club members for $9.50.[33]

Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith, released in 2005 as part of the prequel trilogy, later alluded to the dismissed title Revenge of the Jedi.[34]

Home media[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The original theatrical version of Return of the Jedi was released on VHS and Laserdisc several times between 1986 and 1995,[35] followed by releases of the Special Edition in the same formats between 1997 and 2000. Some of these releases contained featurettes; some were individual releases of just this film, while others were boxed sets of all three original films.

On September 21, 2004, all three original films were released in a boxed set on DVD with additional changes made by George Lucas. The films were digitally restored and remastered, and the DVD also featured English subtitles, Dolby Digital 5.1 EX surround sound, and commentaries by George Lucas, Ben Burtt, Dennis Muren, and Carrie Fisher. The bonus disc included documentaries including Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy and several featurettes including "The Characters of Star Wars", "The Birth of the Lightsaber", and "The Legacy of Star Wars". Also included were teasers, trailers, TV spots, still galleries, and a demo for Star Wars: Battlefront.

With the release of Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, which depicts how and why Anakin Skywalker turned to the dark side of the Force, Lucas once again altered Return of the Jedi to bolster the relationship between the original trilogy and the prequel trilogy. The original and 1997 Special Edition versions of Return of the Jedi featured British theater actor Sebastian Shaw playing both the dying Anakin Skywalker and his ghost. In the 2004 DVD, Shaw's portrayal of Anakin's ghost is replaced by Hayden Christensen, who portrayed Anakin in Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith. All three films in the original unaltered Star Wars trilogy were later released, individually, on DVD on September 12, 2006. These versions were originally slated to only be available until December 31, 2006, although they remained in print until May 2011 and were packaged with the 2004 versions again in a new box set on November 4, 2008.[36] Although the 2004 versions in these sets each feature an audio commentary, no other extra special features were included to commemorate the original cuts. The runtime of the 1997 Special Edition of the film and all subsequent releases is approximately five minutes longer than the original theatrical version.

A Blu-ray Disc version of the Star Wars saga was announced for release in 2011 during Star Wars Celebration V. Several deleted scenes from Return of the Jedi were included for the Blu-ray version, including a sandstorm sequence following the Battle at the Sarlacc Pit, a scene featuring Moff Jerjerrod and Death Star officers during the Battle of Endor, and a scene where Darth Vader communicates with Luke via the Force as Skywalker is assembling his new lightsaber before he infiltrates Jabba's palace.[37] On January 6, 2011, 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment announced the Blu-ray release for September 2011 in three different editions and the cover art was unveiled in May.

On April 7, 2015, Walt Disney Studios, 20th Century Fox, and Lucasfilm jointly announced the digital releases of the six released Star Wars films. Return of the Jedi was released through the iTunes Store, Amazon Video, Vudu, Google Play, and Disney Movies Anywhere on April 10, 2015.[38]

Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment reissued Return of the Jedi on Blu-ray, DVD, and digital download on September 22, 2019.[39] Additionally, all six films were available for 4K HDR and Dolby Atmos streaming on Disney+ upon the service's launch on November 12, 2019.[40] This version of the film was released by Disney on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray box set on March 31, 2020.[41][41]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Return of the Jedi grossed $309.3 million in the United States and Canada, and $166 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $475.3 million, against a production budget of about $32.5 million.[4][5]

The film made $23 million from 1,002 theaters in its opening weekend. It finished first at the box office for six of its first seven weeks of release, only coming in second once behind Superman III in its fourth weekend.[5] Box Office Mojo estimates that the film sold over 80 million tickets in the US in its initial theatrical run.[42] When it was re-released in 1985, it made $11.2 million,[43] which totaled its initial theatrical gross to $385.8 million worldwide.[43]

Critical response[edit]

According to the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 82% of critics have given the film a positive review with an average rating of 7.25/10, based on 94 reviews from critics. The site's critics consensus reads: "Though failing to reach the cinematic heights of its predecessors, Return of the Jedi remains an entertaining sci-fi adventure and a fitting end to the classic trilogy."[44] At Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 58 out of 100 based on 24 reviews from mainstream critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[45]

In 1983, film critic Roger Ebert gave the film four stars out of four, calling it "a complete entertainment, a feast for the eyes and a delight for the fancy. It's a little amazing how Lucas and his associates keep topping themselves."[46] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune also gave the film four stars out of four and wrote, "From the moment that the familiar 'Star Wars' introductory words begin to crawl up the screen, 'Return of the Jedi' is a childlike delight. It's the best video game around. And for the professional moviegoers, it is particularly enjoyable to watch every facet of filmmaking at its best."[47] James Harwood of Variety called the film "a visual treat throughout," but thought that "Hamill is not enough of a dramatic actor to carry the plot load here" and Harrison Ford "is present more in body than in spirit this time, given little to do but react to special effects. And it can't be said that either Carrie Fisher or Billy Dee Williams rise to previous efforts. But Lucas and director Richard Marquand have overwhelmed these performer flaws with a truly amazing array of creatures, old and new, plus the familiar space hardware."[48] Sheila Benson of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film "is fully satisfying, it gives honest value to all the hopes of its believers. With this last of the central 'Star Wars' cycle, there is the sense of the closing of a circle, of leaving behind real friends. It is accomplished with a weight and a new maturity that seem entirely fitting, yet the movie has lost none of its sense of fun; it bursts with new inventiveness."[49]

Gary Arnold of The Washington Post said, "'Return of the Jedi,' a feat of mass enchantment, puts the happy finishing touches on George Lucas' 'Star Wars' saga. It was worth the wait, and the work is now an imposing landmark in contemporary popular culture—a three-part, 6¼-hour science-fiction epic of unabashed heroic proclivities."[50] The film was also featured on the May 23, 1983, TIME magazine cover issue (where it was labeled "Star Wars III"),[51] where the reviewer Gerald Clarke said that while it was not as exciting as the first Star Wars film, it was "better and more satisfying" than The Empire Strikes Back, now considered by many as the best of the original trilogy.[52] Vincent Canby of The New York Times was negative, calling Return of the Jedi "by far the dimmest adventure of the lot"[53] and declaring, "The joys of watching space battles as envisioned by wizards in studios and laboratories are not inexhaustible."[54] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker was also negative, beginning her review with the words: "Some of the trick effects might seem miraculous if the imagery had any lustre, but 'Return of the Jedi' is an impersonal and rather junky piece of moviemaking."[55]

Christopher John reviewed The Return of the Jedi in Ares Magazine #15 and commented that "Star Wars may not be dead, but Return of the Jedi is a failure, and is a cheap and tarnished crown for the series which shook the world of film when it started out . . . a long time ago, in that galaxy far, far away."[56]

James Kendrick of Q Network Film Desk, reviewing the 1997 special edition re-release, assessed Return of the Jedi as "the least of the three" original films, but "still a magnificent experience in its own right. Its main problem is that it tends to lean too much on the slick commercialism generated by the first two installments."[57] ReelViews.net's James Berardinelli wrote about the special edition re-release that:

Although it was great fun re-watching Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back again on the big screen, Return of the Jedi doesn't generate the same sense of enjoyment. And, while Lucas worked diligently to re-invigorate each entry into the trilogy, Jedi needs more than the patches of improved sound, cleaned-up visuals, and a few new scenes. Still, despite the flaws, this is still Star Wars, and, as such, represents a couple of lightly-entertaining hours spent with characters we have gotten to know and love over the years. Return of the Jedi is easily the weakest of the series, but its position as the conclusion makes it a must-see for anyone who has enjoyed its predecessor.[58]

While the action set pieces – particularly the Sarlacc battle sequence, the speeder bike chase on the Endor moon, the space battle between Rebel and Imperial pilots, and Luke Skywalker's duel against Darth Vader – are well-regarded, the ground battle between the Ewoks and Imperial stormtroopers remains a bone of contention.[59] Fans are also divided on the likelihood of Ewoks (being an extremely primitive race of small creatures armed with sticks and rocks) defeating an armed ground force comprising the Empire's "best troops". Lucas has defended the scenario, saying that the Ewoks' purpose was to distract the Imperial troops and that the Ewoks did not really win.[14] His inspiration for the Ewoks' victory came from the Vietnam War, where the indigenous Vietcong forces prevailed against the technologically superior United States.[60]

Accolades[edit]

At the 56th Academy Awards in 1984, Richard Edlund, Dennis Muren, Ken Ralston, and Phil Tippett received the "Special Achievement Award for Visual Effects." Norman Reynolds, Fred Hole, James L. Schoppe, and Michael Ford were nominated for "Best Art Direction/Set Decoration". Ben Burtt received a nomination for "Best Sound Effects Editing". John Williams received the nomination for "Best Music, Original Score". Burtt, Gary Summers, Randy Thom and Tony Dawe all received the nominations for "Best Sound".[61] At the 1984 BAFTA Awards, Edlund, Muren, Ralston, and Kit West won for "Best Special Visual Effects". Tippett and Stuart Freeborn were also nominated for "Best Makeup". Reynolds received a nomination for "Best Production Design/Art Direction". Burtt, Dawe, and Summers also received nominations for "Best Sound". Williams was also nominated "Best Album of Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or Television Special". The film also won for "Best Dramatic Presentation", the older award for science fiction and fantasy in film, at the 1984 Hugo Awards.[62]

- American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies – Nominated[63]

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills – Nominated[64]

Marketing[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Novelization[edit]

The novelization of Return of the Jedi was written by James Kahn and was released on May 12, 1983, thirteen days before the film's release.[65]

Radio drama[edit]

A radio drama adaptation of the film was written by Brian Daley with additional material contributed by John Whitman and was produced for and broadcast on National Public Radio in 1996. It was based on characters and situations created by George Lucas and on the screenplay by Lawrence Kasdan and George Lucas. The first two Star Wars films were similarly adapted for National Public Radio in the early 1980s, but it was not until 1996 that a radio version of Return of the Jedi was heard. Anthony Daniels returned as C-3PO, but Mark Hamill and Billy Dee Williams did not reprise their roles as they had for the first two radio dramas. They were replaced by newcomer Joshua Fardon as Luke Skywalker and character actor Arye Gross as Lando Calrissian. John Lithgow voiced Yoda, whose voice actor in the films has always been Frank Oz. Bernard Behrens returned as Obi-Wan Kenobi and Brock Peters reprised his role as Darth Vader. Veteran character actor Ed Begley, Jr. played Boba Fett. Edward Asner also guest-starred speaking only in grunts as the voice of Jabba the Hutt. The radio drama had a running time of three hours.[66]

Principal production of the show was completed on February 11, 1996. Only hours after celebrating its completion with the cast and crew of the show, Daley died of pancreatic cancer. The show is dedicated to his memory.[citation needed] The cast and crew recorded a get-well message for Daley, but the author never got the chance to hear it. The message is included as part of the Star Wars Trilogy collector's edition box set.[citation needed]

Comic book adaptation[edit]

Marvel Comics published a comic book adaptation of the film by writer Archie Goodwin and artists Al Williamson, Carlos Garzon, Tom Palmer, and Ron Frenz. The adaptation appeared in Marvel Super Special #27[67] and as a four-issue limited series.[68][69] It was later reprinted in a mass market paperback.[70]

Book-and-record set[edit]

Lucasfilm adapted the story for a children's book-and-record set. Released in 1983, the 24-page Star Wars: Return of the Jedi read-along book was accompanied by a 33⅓ rpm 18-centimetre (7 in) gramophone record. Each page of the book contained a cropped frame from the film with an abridged and condensed version of the story. The record was produced by Buena Vista Records.[71]

Prequels and sequels[edit]

A prequel trilogy began with Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, released in 1999, and set three decades before the original trilogy. A sequel trilogy began with Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens in 2015, set 30 years after Return of the Jedi.

See also[edit]

- List of films featuring extraterrestrials

- List of films featuring space stations

- List of Star Wars films

- List of Star Wars television series

- Princess Leia's bikini

References[edit]

- ^ "STAR WARS EPISODE VI: RETURN OF THE JEDI (U)". British Board of Film Classification. May 12, 1983. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History, Scarecrow Press, 1989 p260

- ^ J.W. Rinzler, The Making of Return of the Jedi, Aurum Press, ISBN 978 1 78131 076 2, 2013 p336

- ^ a b "Return of the Jedi". Box Office Mojo. IMDB. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Return of the Jedi". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. 2015. Archived from the original on May 1, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ "Star Wars: Episode VI Return of the Jedi". Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ Hughes, Mark (January 6, 2017). "'Star Wars' Jedi Force-Ghosts Appearing Young In Sequels Makes Perfect Sense". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy Star Wars Trilogy Box Set DVD documentary, [2004]

- ^ Witzke, Sean (February 19, 2015). "A Look Back at Steven Spielberg at the Height of His Powers". Grantland. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "David Lynch Meets George Lucas". YouTube. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Shawn Adler (September 20, 2007). "Cronenberg's Aborted Job Offer: Star Wars: Return of the Jedi Director's Chair?" Archived March 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. MTV Movies Blog

- ^ Ryan, Joal (May 24, 2013). "The 'Return of the Jedi' That Could Have Been". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ Dale Pollock (1999). Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas. Da Capo. ISBN 0-573-60606-4.

- ^ a b c Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi DVD commentary featuring George Lucas, Ben Burtt, Dennis Muren and Carrie Fisher. Fox Home Entertainment, 2004

- ^ a b c Marcus Hearn (2005). "Cliffhanging". The Cinema of George Lucas. New York City: Harry N. Abrams Inc. pp. 140–1. ISBN 0-8109-4968-7.

- ^ a b c Richard Patterson (June 1983). "Return of the Jedi: Production and Direction, p. 3". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ Howard Kazanjian interview, "[1] Archived February 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Geoff Boucher (August 12, 2010). "Did Star Wars become a toy story? Producer Gary Kurtz looks back" Archived August 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times, Calendar section

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith DVD commentary featuring George Lucas, Rick McCallum, Rob Coleman, John Knoll, and Roger Guyett. Fox Home Entertainment, 2005

- ^ George Lucas (June 12, 1981). "Star Wars — Episode VI: "Revenge of the Jedi" Revised Rough Draft". Starkiller. Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ^ "Map of the Movies" (PDF). Humboldt - Del Norte Film Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Richard Patterson (June 1983). "Return of the Jedi: Production and Direction, p. 4". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Richard Patterson (June 1983). "Return of the Jedi: Production and Direction, p. 1". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ Hesseltine, Cassandra. "Complete Filmography of Humboldt County". Humboldt Del Norte Film Commission. Humboldt Del Norte Film Commission. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ "Return of the Jedi: Steadicam Plates, p. 3". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ Daniels, Anthony (2019). I Am C-3PO: The Inside Story. DK. ISBN 9781465492562.

- ^ "When John Williams Can't Go, Whom Does Spielberg Call? Thomas Newman". NPR.org. October 17, 2015. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "Star Wars / The Empire Strikes Back / Return of the Jedi (Original Soundtracks – 2004 reissue)". Archived from the original on November 27, 2006. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- ^ "Return of the Jedi: Production and Direction, p. 2". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ "Episode VI: What Has Changed?". StarWars.com. September 8, 2006. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Revenge of the Jedi Trailer from Star Wars Trilogy Box Set DVD Bonus Disc, [2004]

- ^ Sansweet & Vilmur (2004). The Star Wars Poster Book. Chronicle Books. p. 124.

- ^ Greg Dean Schmitz. "Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith — Greg's Preview". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved March 5, 2007.

- ^ "Star Wars Home Video Timeline: Return of the Jedi". davisdvd.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ^ "Star Wars Saga Repacked in Trilogy Sets on DVD". Lucasfilm. StarWars.com. August 28, 2008. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved November 8, 2008.

- ^ "George Lucas Announces Star Wars on Blu-Ray at Celebration V". Lucasfilm. StarWars.com. August 14, 2010. Archived from the original on August 16, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ Vlessing, Etan (April 6, 2015). "'Star Wars' Movie Franchise Headed to Digital HD". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Bonomolo, Cameron (August 8, 2019). "Newest Star Wars Saga Blu-rays Get Matching Artwork". Comicbook.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ Hayes, Dade (April 11, 2019). "Entire 'Star Wars' Franchise Will Be On Disney+ Within Its First Year". Deadline. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ a b "Star Wars: Skywalker Saga 27-disc Ultra HD 4K Blu-ray set now up for preorder". Film Stories. January 7, 2020. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ "Return of the Jedi (1983)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ a b "Star Wars: Episode VI - Return of the Jedi". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ "Star Wars: Episode VI - Return of the Jedi (1983)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ "Star Wars: Episode VI - Return of the Jedi Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (May 25, 1983). "Return of the Jedi". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (May 25, 1983). "'Return of the Jedi': Another quality toy in 'Star Wars' line". Chicago Tribune. Section 4, p. 1.

- ^ Harwood, James (May 18, 1983). "Film Reviews: Return Of The Jedi". Archived August 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Variety. 14.

- ^ Benson, Sheila (May 25, 1983). "'Star Wars' Continues with an Inventive 'Jedi'". Los Angeles Times. Part VI, p. 1.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (May 22, 1983). "Both Magical & Monstrous, the 'Star Wars' Finale Is a Triumph". Archived October 7, 2018, at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post. G1.

- ^ "Star Wars III: Return of the Jedi". Time. May 23, 1983. Archived from the original on March 23, 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- ^ Clarke, Gerald (May 23, 1983). "Great Galloping Galaxies". Time. Archived from the original on November 24, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (May 25, 1983). "Lucas Returns With the 'Jedi'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (May 29, 1983). "The Force Is With Them, But the Magic Is Gone". Archived May 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times. H15.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (May 30, 1983). "The Current Cinema: Fun Machines". The New Yorker. 88.

- ^ John, Christopher (Fall 1983). "Film". Ares Magazine. TSR, Inc. (15): 10–11.

- ^ Kendrick, James. "Star Wars: Episode VI—Return of the Jedi: Special Edition Review of "Return"". Q Network. Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Berardinelli, James. "Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi - Reelviews Movie Reviews". Reelviews Movie Reviews.

- ^ "The best – and worst – movie battle scenes". CNN. March 30, 2007. Archived from the original on April 8, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ Rinzler, J.W. The Making of Star Wars: Return of the Jedi.

- ^ "The 56th Academy Awards (1984) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ "Awards for Star Wars: Episode VI — Return of the Jedi (1983)". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on March 26, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ^ Star Wars, Episode VI — Return of the Jedi (Mass Market Paperback). Amazon.com. ISBN 0345307674.

- ^ "Return of the Jedi Produced by NPR". HighBridge Audio. Archived from the original on November 5, 2006. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ "GCD :: Issue :: Marvel Super Special #27". comics.org. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Star Wars: Return of the Jedi Archived February 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Edwards, Ted (1999). "Adventures in the Comics". The Unauthorized Star Wars Compendium. Little, Brown and Company. p. 87. ISBN 9780316329293.

The adaptation of Return of the Jedi was published in Marvel Super Special #27 and in a separate miniseries, once again penciled by Al Williamson and inked by Carlos Garzon.

- ^ The Marvel Comics Illustrated Version of Star Wars Return of the Jedi Archived February 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ "Star Wars In The UK: Read Along Adventures". Archived from the original on January 20, 2018.

Sources[edit]

Arnold, Alan. Once Upon a Galaxy: A Journal of Making the Empire Strikes Back. Sphere Books, London. 1980. ISBN 978-0-345-29075-5.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Return of the Jedi |

- Official website at StarWars.com

- Official website at Lucasfilm.com

- Star Wars: Episode VI Return of the Jedi on Wookieepedia, a Star Wars wiki

- Return of the Jedi on IMDb

- Return of the Jedi at the TCM Movie Database

- Return of the Jedi at AllMovie

- Return of the Jedi at Rotten Tomatoes

- Return of the Jedi at Box Office Mojo

- Return of the Jedi at Metacritic

- Return of the Jedi at The Numbers

- Return of the Jedi at the American Film Institute Catalog

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial |

Saturn Award for Best Science Fiction Film 1983 |

Succeeded by The Terminator |

- 1983 films

- English-language films

- Return of the Jedi

- American films

- Star Wars films

- 1980s science fiction action films

- American epic films

- American action adventure films

- American science fantasy films

- American science fiction action films

- American science fiction war films

- American space adventure films

- American sequel films

- Cyborg films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Family in fiction

- Films about orphans

- Films about rebellions

- Films about twins

- Films adapted into radio programs

- Films featuring puppetry

- Films set in forests

- Films set on fictional moons

- Films shot in Arizona

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Hertfordshire

- Films using stop-motion animation

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation winning works

- Jedi

- Prosthetics in fiction

- Rebellions in fiction

- Fiction about regicide

- American science fiction adventure films

- Films shot at Elstree Studios

- Lucasfilm films

- 20th Century Fox films

- Films scored by John Williams

- Films directed by Richard Marquand

- Films produced by Howard Kazanjian

- Films with screenplays by George Lucas

- Guerrilla warfare in film