Last Supper

The Last Supper is the final meal that, in the Gospel accounts, Jesus shared with his apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion.[2] The Last Supper is commemorated by Christians especially on Maundy Thursday.[3] The Last Supper provides the scriptural basis for the Eucharist, also known as "Holy Communion" or "The Lord's Supper".[4]

The First Epistle to the Corinthians contains the earliest known mention of the Last Supper. The four canonical Gospels all state that the Last Supper took place towards the end of the week, after Jesus's triumphal entry into Jerusalem and that Jesus and his apostles shared a meal shortly before Jesus was crucified at the end of that week.[5][6] During the meal Jesus predicts his betrayal by one of the apostles present, and foretells that before the next morning, Peter will thrice deny knowing him.[5][6]

The three Synoptic Gospels and the First Epistle to the Corinthians include the account of the institution of the Eucharist in which Jesus takes bread, breaks it and gives it to others, saying "This is my body given to you" (the apostles are not explicitly mentioned in the account in First Corinthians).[5][6] The Gospel of John does not include this episode, but tells of Jesus washing the feet of the apostles, giving the new commandment "to love one another as I have loved you", and has a detailed farewell discourse by Jesus, calling the apostles who follow his teachings "friends and not servants", as he prepares them for his departure.[7][8]

Scholars have looked to the Last Supper as the source of early Christian Eucharistic traditions.[9][10] Others see the account of the Last Supper as derived from 1st-century eucharistic practice[10][11] as described by Paul in the mid-50s.

Terminology[edit]

The term "Last Supper" does not appear in the New Testament,[12][13] but traditionally many Christians refer to such an event.[13] Many Protestants use the term "Lord's Supper", stating that the term "last" suggests this was one of several meals and not the meal.[14][15] The term "Lord's Supper" refers both to the biblical event and the act of "Holy Communion" and Eucharistic ("thanksgiving") celebration within their liturgy. Evangelical Protestants also use the term "Lord's Supper", but most do not use the terms "Eucharist" or the word "Holy" with the name "Communion".[16]

The Eastern Orthodox use the term "Mystical Supper" which refers both to the biblical event and the act of Eucharistic celebration within liturgy.[17] The Russian Orthodox also use the term "Secret Supper" (Church Slavonic: "Тайная вечеря", Taynaya vecherya).

Scriptural basis[edit]

The last meal that Jesus shared with his apostles, or disciples, is described in all four canonical Gospels (Mt. 26:17–30, Mk. 14:12–26, Lk. 22:7–39 and Jn. 13:1–17:26). This meal later became known as the Last Supper.[6] The Last Supper was likely a retelling of the events of the last meal of Jesus among the early Christian community, and became a ritual which recounted that meal.[18]

Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians,[11:23–26] which was likely written before the Gospels, includes a reference to the Last Supper but emphasizes the theological basis rather than giving a detailed description of the event or its background.[5][6]

Background and setting[edit]

The overall narrative that is shared in all Gospel accounts that leads to the Last Supper is that after the Triumphal entry into Jerusalem early in the week, and encounters with various people and the Jewish elders, Jesus and his disciples share a meal towards the end of the week. After the meal, Jesus is betrayed, arrested, tried, and then crucified.[5][6]

Key events in the meal are the preparation of the disciples for the departure of Jesus, the predictions about the impending betrayal of Jesus, and the foretelling of the upcoming denial of Jesus by Apostle Peter.[5][6]

Prediction of Judas' betrayal[edit]

In Matthew 26:24–25, Mark 14:18–21, Luke 22:21–23 and John 13:21–30 during the meal, Jesus predicted that one of the apostles present would betray him.[19] Jesus is described as reiterating, despite each apostle's assertion that he would not betray Jesus, that the betrayer would be one of those who were present, and saying that there would be "woe to the man who betrays the Son of man! It would be better for him if he had not been born."[20]

In Matthew 26:23–25 and John 13:26–27, Judas is specifically identified as the traitor. In the Gospel of John, when asked about the traitor, Jesus states:

"It is the one to whom I will give this piece of bread when I have dipped it in the dish." Then, dipping the piece of bread, he gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot. As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him.[5][6]

Institution of the Eucharist[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Death and Resurrection of Jesus |

|---|

|

|

Visions of Jesus |

|

Empty tomb fringe theories |

|

Portals: |

The three Synoptic Gospel accounts give somewhat different versions of the order of the meal. In chapter 26 of the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus prays thanks for the bread, divides it, and hands the pieces of bread to his disciples, saying "Take, eat, this is my body." Later in the meal Jesus takes a cup of wine, offers another prayer, and gives it to those present, saying "Drink from it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I will never again drink of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom."

In chapter 22 of the Gospel of Luke, however, the wine is blessed and distributed before the bread, followed by the bread, then by a second, larger cup of wine, as well as somewhat different wordings. Additionally, according to Paul and Luke, he tells the disciples "do this in remembrance of me." This event has been regarded by Christians of most denominations as the institution of the Eucharist. There is recorded celebration of the Eucharist by the early Christian community in Jerusalem.[7]

The institution of the Eucharist is recorded in the three Synoptic Gospels and in Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians. As noted above, Jesus's words differ slightly in each account. In addition, Luke 22:19b–20 is a disputed text which does not appear in some of the early manuscripts of Luke. Some scholars, therefore, believe that it is an interpolation, while others have argued that it is original.[21][22]

A comparison of the accounts given in the Gospels and 1 Corinthians is shown in the table below, with text from the ASV. The disputed text from Luke 22:19b–20 is in italics.

| Mark 14:22–24 | And as they were eating, he took bread, and when he had blessed, he brake it, and gave to them, and said, Take ye: this is my body. | And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave to them: and they all drank of it. And he said unto them, 'This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.' |

|---|---|---|

| Matthew 26:26–28 | And as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and brake it; and he gave to the disciples, and said, 'Take, eat; this is my body.' | And he took a cup, and gave thanks, and gave to them, saying, 'Drink ye all of it; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many unto remission of sins.' |

| 1 Corinthians 11:23–25 | For I received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, that the Lord Jesus in the night in which he was betrayed took bread; and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, 'This is my body, which is for you: this do in remembrance of me.' | In like manner also the cup, after supper, saying, 'This cup is the new covenant in my blood: this do, as often as ye drink it, in remembrance of me.' |

| Luke 22:19–20 | And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and gave to them, saying, 'This is my body which is given for you: this do in remembrance of me.' | And the cup in like manner after supper, saying, 'This cup is the new covenant in my blood, even that which is poured out for you.' |

Jesus' actions in sharing the bread and wine have been linked with Isaiah 53:12 which refers to a blood sacrifice that, as recounted in Exodus 24:8, Moses offered in order to seal a covenant with God. Some scholars interpret the description of Jesus' action as asking his disciples to consider themselves part of a sacrifice, where Jesus is the one due to physically undergo it.[23]

Although the Gospel of John does not include a description of the bread and wine ritual during the Last Supper, most scholars agree that John 6:58–59 (the Bread of Life Discourse) has a Eucharistic nature and resonates with the "words of institution" used in the Synoptic Gospels and the Pauline writings on the Last Supper.[24]

Prediction of Peter's denial[edit]

In Matthew 26:33–35, Mark 14:29–31, Luke 22:33–34 and John 13:36–8 Jesus predicts that Peter will deny knowledge of him, stating that Peter will disown him three times before the rooster crows the next morning. The three Synoptic Gospels mention that after the arrest of Jesus, Peter denied knowing him three times, but after the third denial, heard the rooster crow and recalled the prediction as Jesus turned to look at him. Peter then began to cry bitterly.[25][26]

Elements unique to the Gospel of John[edit]

In John, Jesus's last supper is not explicitly referred to as a Passover meal. Furthermore, John's recounting of events has the crucifixion taking place concurrently with the evening Passover meal. Recent scholarship suggests that John's chronological peculiarity is a result of his use of a more modern calendar than the one that would have been in use when Jesus was alive years earlier.

John 13 includes the account of the washing the feet of the Apostles by Jesus before the meal.[27] In this episode, Apostle Peter objects and does not want to allow Jesus to wash his feet, but Jesus answers him, "Unless I wash you, you have no part with me",[Jn 13:8] after which Peter agrees.

In the Gospel of John, after the departure of Judas from the Last Supper, Jesus tells his remaining disciples [John 13:33] that he will be with them for only a short time, then gives them a New Commandment, stating:[28][29] "A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another." in John 13:34–35. Two similar statements also appear later in John 15:12: "My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you", and John 15:17: "This is my command: Love each other."[29]

At the Last Supper in the Gospel of John, Jesus gives an extended sermon to his disciples.[John 14–16] This discourse resembles farewell speeches called testaments, in which a father or religious leader, often on the deathbed, leaves instructions for his children or followers.[30]

This sermon is referred to as the Farewell discourse of Jesus, and has historically been considered a source of Christian doctrine, particularly on the subject of Christology. John 17:1–26 is generally known as the Farewell Prayer or the High Priestly Prayer, given that it is an intercession for the coming Church.[31] The prayer begins with Jesus's petition for his glorification by the Father, given that completion of his work and continues to an intercession for the success of the works of his disciples and the community of his followers.[31]

Time and place[edit]

Date[edit]

Historians estimate that the date of the crucifixion fell in the range AD 30–36.[32][33][34] Physicists such as Isaac Newton and Colin Humphreys have ruled out the years 31, 32, 35, and 36 on astronomical grounds, leaving 7 April AD 30 and 3 April AD 33 as possible crucifixion dates.[35] Humphreys proposes narrowing down the date of the Last Supper as having occurred in the evening of Wednesday, 1 April AD 33,[36] by revising Annie Jaubert's double-Passover theory.

All Gospels agree that Jesus held a Last Supper with his disciples prior to dying on a Friday at or just before the time of Passover (annually on 15 Nisan, the official Jewish day beginning at sunset) and that his body was left in the tomb for the whole of the next day, which was a Shabbat (Saturday).[Mk. 15:42] [16:1–2] However, while the Synoptic Gospels present the Last Supper as a Passover meal,[Matt. 26:17][Mk. 14:1–2] [Lk 22:1–15] the Gospel of John makes no explicit mention that the Last Supper was a Passover meal and presents the official Jewish Passover feast as beginning in the evening a few hours after the death of Jesus. John thus implies that the Friday of the crucifixion was the day of preparation for the feast (14 Nisan), not the feast itself (15 Nisan), and astronomical calculations of ancient Passover dates initiated by Isaac Newton, and posthumously published in 1733, support John's chronology.[37]

Historically, various attempts to reconcile the three synoptic accounts with John have been made, some of which are indicated in the Last Supper by Francis Mershman in the 1912 Catholic Encyclopedia.[38] The Maundy Thursday church tradition assumes that the Last Supper was held on the evening before the crucifixion day (although, strictly speaking, in no Gospel is it unequivocally said that this meal took place on the night before Jesus died).[39]

A new approach to resolve this contrast was undertaken in the wake of the excavations at Qumran in the 1950s when Annie Jaubert argued that there were two Passover feast dates: while the official Jewish lunar calendar had Passover begin on a Friday evening in the year that Jesus died, a solar calendar was also used, for instance by the Essene community at Qumran, which always had the Passover feast begin on a Tuesday evening. According to Jaubert, Jesus would have celebrated the Passover on Tuesday, and the Jewish authorities three days later, on Friday.[40]

However, Humphreys has calculated that Jaubert's proposal cannot be correct, as the Qumran solar Passover would always fall after the official Jewish lunar Passover. Nevertheless, he agrees with the approach of two Passover dates, and argues that the Last Supper took place on the evening of Wednesday 1 April 33, based on his recent discovery of the Essene, Samaritan, and Zealot lunar calendar, which is based on Egyptian reckoning.[41][42] Humphreys' implication is that Jesus and other communities were following the original Hebrew calendar putatively imported from Egypt by Moses (which requires calculating the time of the invisible new moon), rather than the official Jewish calendar which had been adopted more recently, in the 6th century BC during the Babylonian exile (which simply requires observing the visible waxing moon). A Last Supper on Wednesday, he argues, would allow more time than in the traditional view (Last Supper on Thursday) for the various interrogations of Jesus and his presentation to Pilate before he was crucified on Friday. Furthermore, a Wednesday Last Supper, followed by a Thursday daylight Sanhedrin trial, followed by a Friday judicial confirmation and crucifixion would not require violating Jewish court procedure as documented in the 2nd century, which forbade capital trials at night and moreover required a confirmatory session the following day.

In a review of Humphreys' book, the Bible scholar William R Telford points out that the non-astronomical parts of his argument are based on the assumption that the chronologies described in the New Testament are historical and based on eyewitness testimony. In doing so, Telford says, Humphreys has built an argument upon unsound premises which "does violence to the nature of the biblical texts, whose mixture of fact and fiction, tradition and redaction, history and myth all make the rigid application of the scientific tool of astronomy to their putative data a misconstrued enterprise."[43]

Location[edit]

According to later tradition, the Last Supper took place in what is today called The Room of the Last Supper on Mount Zion, just outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem, and is traditionally known as The Upper Room. This is based on the account in the Synoptic Gospels that states that Jesus had instructed two disciples (Luke 22:8 specifies that Jesus sent Peter and John) to go to "the city" to meet "a man carrying a jar of water", who would lead them to a house, where they would find "a large upper room furnished and ready".[Mark 14:13–15] In this upper room they "prepare the Passover".

Bargil Pixner claims the original site is located beneath the current structure of the Cenacle on Mount Zion.[44]

No more specific indication of the location is given in the New Testament, and the "city" referred to may be a suburb of Jerusalem, such as Bethany, rather than Jerusalem itself. The traditional location is in an area that, according to archaeology, had a large Essene community, a point made by scholars who suspect a link between Jesus and the group.[45][incomplete short citation]

Saint Mark's Syrian Orthodox Church in Jerusalem is another possible site for the room in which the Last Supper was held, and contains a Christian stone inscription testifying to early reverence for that spot. Certainly the room they have is older than that of the current coenaculum (crusader – 12th century) and as the room is now underground the relative altitude is correct (the streets of 1st century Jerusalem were at least twelve feet (3.7 metres) lower than those of today, so any true building of that time would have even its upper story currently under the earth). They also have a revered Icon of the Virgin Mary, reputedly painted from life by St Luke.

Theology of the Last Supper[edit]

St. Thomas Aquinas viewed The Father, Christ, and the Holy Spirit as teachers and masters who provide lessons, at times by example. For Aquinas, the Last Supper and the Cross form the summit of the teaching that wisdom flows from intrinsic grace, rather than external power.[46] For Aquinas, at the Last Supper Christ taught by example, showing the value of humility (as reflected in John's foot washing narrative) and self-sacrifice, rather than by exhibiting external, miraculous powers.[46][47]

Aquinas stated that based on John 15:15 (in the Farewell discourse) in which Jesus said: "No longer do I call you servants; ...but I have called you friends". Those who are followers of Christ and partake in the Sacrament of the Eucharist become his friends, as those gathered at the table of the Last Supper.[46][47][48] For Aquinas, at the Last Supper Christ made the promise to be present in the Sacrament of the Eucharist, and to be with those who partake in it, as he was with his disciples at the Last Supper.[49]

John Calvin believed only in the two sacraments of Baptism and the "Lord's Supper" (i.e., Eucharist). Thus, his analysis of the Gospel accounts of the Last Supper was an important part of his entire theology.[50][51] Calvin related the Synoptic Gospel accounts of the Last Supper with the Bread of Life Discourse in John 6:35 that states: "I am the bread of life. He who comes to me will never go hungry."[51]

Calvin also believed that the acts of Jesus at the Last Supper should be followed as an example, stating that just as Jesus gave thanks to the Father before breaking the bread,[1 Cor. 11:24] those who go to the "Lord's Table" to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist must give thanks for the "boundless love of God" and celebrate the sacrament with both joy and thanksgiving.[51]

Remembrances[edit]

The institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper is remembered by Roman Catholics as one of the Luminous Mysteries of the Rosary, the First Station of a so-called New Way of the Cross and by Christians as the "inauguration of the New Covenant", mentioned by the prophet Jeremiah, fulfilled at the last supper when Jesus "took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to them, and said, 'Take; this is my body.' And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, and they all drank of it. And he said to them, 'This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.'"[Mk. 14:22–24] [Mt. 26:26–28][Lk. 22:19–20] Other Christian groups consider the Bread and Wine remembrance to be a change to the Passover ceremony, as Jesus Christ has become "our Passover, sacrificed for us",[1 Cor. 5:7] and hold that partaking of the Passover Communion (or fellowship) is now the sign of the New Covenant, when properly understood by the practicing believer.

These meals evolved into more formal worship services and became codified as the Mass in the Catholic Church, and as the Divine Liturgy in the Eastern Orthodox Church; at these liturgies, Catholics and Eastern Orthodox celebrate the Sacrament of the Eucharist. The name "Eucharist" is from the Greek word εὐχαριστία (eucharistia) which means "thanksgiving".

Early Christianity observed a ritual meal known as the "agape feast"[52] These "love feasts" were apparently a full meal, with each participant bringing food, and with the meal eaten in a common room. They were held on Sundays, which became known as the Lord's Day, to recall the resurrection, the appearance of Christ to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, the appearance to Thomas and the Pentecost which all took place on Sundays after the Passion.

Passover parallels[edit]

Since the late 20th century, with growing consciousness of the Jewish character of the early church and the improvement of Jewish-Christian relations, it became common among some lay people to associate the Last Supper with the Jewish Seder. This is due to the fact that the Synoptic Gospels describe it as a Passover Meal. Some evangelical groups borrowed Seder customs, like Haggadahs, and incorporated them in new rituals meant to mimic the Last Supper; likewise, many secularized Jews presume that the event was a Seder. This identification is somewhat erroneous, as although it was most likely a Passover Meal, it was according to the Second Temple Period customs and included the consumption of a full lamb. The earliest elements in the current Passover Seder (a fortiori the full-fledged ritual, which is first recorded in full only in the ninth century) are a rabbinic enactment instituted in remembrance of the Temple, which was still standing during the Last Supper.[53]

The fifth chapter in the Quran, Al-Ma'ida (the table) contains a reference to a meal (Sura 5:114) with a table sent down from God to ʿĪsá (i.e., Jesus) and the apostles (Hawariyyin). However, there is nothing in Sura 5:114 to indicate that Jesus was celebrating that meal regarding his impending death, especially as the Quran states that Jesus was never crucified to begin with. Thus, although Sura 5:114 refers to "a meal", there is no indication that it is the Last Supper.[54] However, some scholars believe that Jesus' manner of speech during which the table was sent down suggests that it was an affirmation of the apostles' resolves and to strengthen their faiths as the impending trial was about to befall them.[55]

Historicity[edit]

Jesus having a final meal with his disciples is almost beyond dispute among scholars, and belongs to the framework of the narrative of Jesus's life.[56]

Some Jesus Seminar scholars consider the Lord's supper to have derived not from Jesus' last supper with the disciples but rather from the gentile tradition of memorial dinners for the dead.[57] In this view, the Last Supper is a tradition associated mainly with the gentile churches that Paul established, rather than with the earlier, Jewish congregations.[57]

Luke is the only Gospel in which Jesus tells his disciples to repeat the ritual of bread and wine.[58] Bart D. Ehrman states that these particular lines do not appear in certain ancient manuscripts and might not be original to the text.[59] However, it is in the earliest Greek manuscripts, e.g. P75, Sinaticus, Vaticanus and Ephraemi Rescriptus.

Many early Church Fathers have attested to the belief that at the Last Supper, Christ made the promise to be present in the Sacrament of the Eucharist, with attestations dating back to the first century AD.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67] The teaching was also affirmed by many councils throughout the Church's history.[68][69]

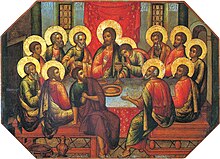

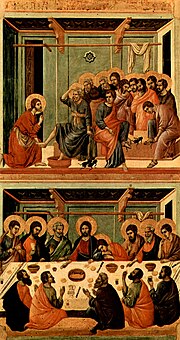

Artistic depictions[edit]

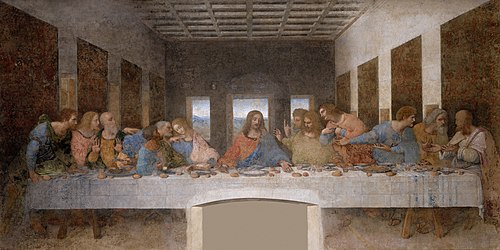

The Last Supper has been a popular subject in Christian art.[1] Such depictions date back to early Christianity and can be seen in the Catacombs of Rome. Byzantine artists frequently focused on the Apostles receiving Communion, rather than the reclining figures having a meal. By the Renaissance, the Last Supper was a favorite topic in Italian art.[70]

There are three major themes in the depictions of the Last Supper: the first is the dramatic and dynamic depiction of Jesus's announcement of his betrayal. The second is the moment of the institution of the tradition of the Eucharist. The depictions here are generally solemn and mystical. The third major theme is the farewell of Jesus to his disciples, in which Judas Iscariot is no longer present, having left the supper. The depictions here are generally melancholy, as Jesus prepares his disciples for his departure.[1] There are also other, less frequently depicted scenes, such as the washing of the feet of the disciples.[71]

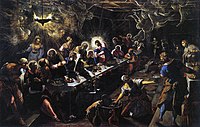

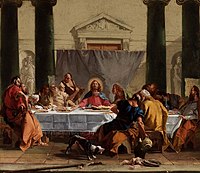

Well known examples include Leonardo da Vinci's depiction, which is considered the first work of High Renaissance art due to its high level of harmony,[72] Tintoretto's depiction which is unusual in that it includes secondary characters carrying or taking the dishes from the table[73] and Salvadore Dali's depiction combines the typical Christian themes with modern approaches of Surrealism.[74]

- Depictions of Last Supper

The Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci, late 15th century

The Last Supper, by Tintoretto, 1592–1594

The first Eucharist, depicted by Juan de Juanes in The Last Supper, c. 1562

The Last Supper by Lazzaro Pisani, the altarpiece of Corpus Christi Parish Church in Għasri, Malta

Communion of the Apostles, by Fra Angelico, with donor portrait, 1440–41

Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1480, depicting Judas separately

Valentin de Boulogne, 1625–1626

Last Supper by Jaume Huguet, c. 1470

Last Supper by Tiepolo, c. 1760

The Last Supper, by Bouveret, 19th century

Last Supper, by Gustave Van de Woestijne, 1927

Music[edit]

The Lutheran Passion hymn "Da der Herr Christ zu Tische saß" (When the Lord Christ sat at the table) derives from a depiction of the Last Supper.[example's importance?]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Gospel figures in art by Stefano Zuffi 2003 ISBN 978-0892367276 pp. 254–59

- ^ "Last Supper. The final meal Christ with His Apostles on the night before the Crucifixion.", Cross, F. L., & Livingstone, E. A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed. rev.) (958). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Gwyneth Windsor, John Hughes (21 November 1990). Worship and Festivals. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0435302733. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

On the Thursday, which is known as Holy Thursday, Christians remember the Last Supper which Jesus had with His disciples. It was the Jewish Feast of the Passover, and the meal which they had together was the traditional Seder feast, eaten that evening by the Jews everywhere.

- ^ Walter Hazen (1 September 2002). Inside Christianity. Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 978-0787705596. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

The Anglican Church in England uses the term Holy Communion. In the Roman Catholic Church, both terms are used. Most Protestant churches refer to it simply as communion or The Lord's Supper. Communion reenacts the Last Supper that Jesus ate with His disciples before he was arrested and crucified.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary by Craig A. Evans 2003 ISBN 0781438683 pp. 465–77

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 4 by Erwin Fahlbusch, 2005 ISBN 978-0802824165 pp. 52–56

- ^ a b Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church / editors, F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone 2005 ISBN 978-0192802903, article Eucharist

- ^ The Gospel according to John by Colin G. Kruse 2004 ISBN 0802827713 p. 103

- ^ "The custom of placing the eucharist at the heart of the worship and fellowship of the Church may have been inspired not only by the disciples’ memory of the Last Supper with Jesus but also by the memory of their fellowship meals with Him during both His days on earth and the forty days of His risen appearances.", Bromiley, G. W. (1988; 2002). Vol. 3: The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised (164). Wm. B. Eerdmans.

- ^ a b The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford University Press, US. 2005. ISBN 0195138864

- ^ Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. Introduction, pp. 1–40

- ^ An Episcopal dictionary of the church by Donald S. Armentrout, Robert Boak Slocum 2005 ISBN 0898692113 p. 292

- ^ a b The Gospel according to Luke: introduction, translation, and notes, Volume 28, Part 1 by Joseph A. Fitzmyer 1995 ISBN 0385005156 p. 1378

- ^ The Companion to the Book of Common Worship by Peter C. Bower 2003 ISBN 0664502326 pp. 115–16

- ^ Liturgical year: the worship of God Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) 1992 ISBN 978-0664253509 p. 37

- ^ Humanists and Reformers: A History of the Renaissance and Reformation by Bard Thompson 1996 ISBN 978-0802863485 pp. 493–94

- ^ The Orthodox Church by John Anthony McGuckin 2010 ISBN 978-1444337310 pp. 293, 297

- ^ The church according to the New Testament by Daniel J. Harrington 2001 ISBN 1580511112 p. 49

- ^ Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0805494448 p. 182

- ^ Mark 14:20–21

- ^ "Lord's Supper, The" in New Bible Dictionary, 3rd edition; IVP, 1996; p. 697

- ^ Craig Blomberg (1997), Jesus and the Gospels, Apollos, p. 333

- ^ (Brown et al. 626)

- ^ Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible 2000 ISBN 9053565035 p. 792

- ^ Peter: apostle for the whole church by Pheme Perkins 2000 ISBN 0567087433 p. 85

- ^ The Gospel according to Matthew, Volume 1 by Johann Peter Lange 1865 Published by Charles Scribner Co, NY p. 499

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "John" pp. 302–10

- ^ Encountering John: The Gospel in Historical, Literary, and Theological Perspective by Andreas J. Kostenberger 2002 ISBN 0801026032 pp. 149–51

- ^ a b 1, 2, and 3 John by Robert W. Yarbrough 2008 ISBN 0801026873 Baker Academic Press p. 215

- ^ Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. 1993.

- ^ a b The Gospel according to John by Herman Ridderbos 1997 ISBN 978-0802804532 The Farewell Prayer: pp. 546–76

- ^ Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times by Paul Barnett 2002 ISBN 0830826998 pp. 19–21

- ^ Paul's early period: chronology, mission strategy, theology by Rainer Riesner 1997 ISBN 978-0802841667 pp. 19–27 (p. 27 has a table of various scholarly estimates)

- ^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0805443653 pp. 77–79

- ^ Colin J. Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0521732000, pp. 62–63 [1]

- ^ Humphreys 2011, p. 72 and p.189

- ^ Pratt, J. P. (3 September 1991). "Newton's Date for the Crucifixion". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 32 (3): 301. Bibcode:1991QJRAS..32..301P.

- ^ Mershman, Francis (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Judaism and Christianity in the first century". google.com.

- ^ Pope Benedict XVI (2011). "The Dating of the Last Supper". Jesus of Nazareth. Catholic Truth Society and Ignatius Press. pp. 106–15. ISBN 978-1586175009.

- ^ Humphreys 2011, pp. 164, 168

- ^ Staff Reporter (18 April 2011). "Last Supper was on Wednesday, not Thursday, challenges Cambridge professor Colin Humphreys". International Business Times. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ Telford, William R. (2015). "Review of The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus". The Journal of Theological Studies. 66 (1): 371–76. doi:10.1093/jts/flv005. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Bargil Pixner, The Church of the Apostles found on Mount Zion, Biblical Archaeology Review 16.3 May/June 1990 [2] Archived 9 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kilgallen 265

- ^ a b c Reading John with St. Thomas Aquinas by Michael Dauphinais, Matthew Levering 2005 ISBN 9780813214054 p. xix

- ^ a b A–Z of Thomas Aquinas by Joseph Peter Wawrykow 2005 ISBN 0334040124 pp. 124–25

- ^ The ethics of Aquinas by Stephen J. Pope 2002 ISBN 0878408886 p. 22

- ^ The Westminster Handbook to Thomas Aquinas by Joseph Peter Wawrykow 2005 ISBN 978-0664224691 p. 124

- ^ Reformed worship by Howard L. Rice, James C. Huffstutler 2001 ISBN 0664501478 pp. 66–68

- ^ a b c Calvin's Passion for the Church and the Holy Spirit by David S. Chen 2008 ISBN 978-1606473467 pp. 62–68

- ^ Agape is one of the four main Greek words for love (The Four Loves by C. S. Lewis). It refers to the idealised or high-level unconditional love rather than lust, friendship, or affection (as in parental affection). Though Christians interpret Agape as meaning a divine form of love beyond human forms, in modern Greek the term is used in the sense of "I love you" (romantic love).

- ^ for example: Jesus Didn’t Eat a Seder Meal, Christianity Today, 6 April 2017.

- ^ Christology in dialogue with Muslims by Ivor Mark Beaumont 2005 ISBN 1870345460 p. 145

- ^ Khalife, Maan (2012). "Last Supper of Jesus According to Islam".

- ^ Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin Books. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0140144994.

- ^ a b Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "Mark," pp. 51–161

- ^ Vermes, Geza. The authentic gospel of Jesus. London, Penguin Books. 2004.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D.. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 978-0060738174

- ^ The Martyr, Justin. "The First Apology".

- ^ of Lyons, Irenaeus. "Against Heresies".

- ^ of Alexandria, Clement. "The Paedagogus (Book I)".

- ^ of Antioch, Ignatius. "The Epistle of Ignatius to the Smyrnaeans".

- ^ of Antioch, Ignatius. "The Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians".

- ^ of Antioch, Ignatius. "The Epistle of Ignatius to the Romans".

- ^ Tertullian. "On the Resurrection of the Flesh".

- ^ Augustine. "Exposition on Psalm 33 (mistakenly labelled 34)".

- ^ "First Council of Nicæa (A.D. 325)".

- ^ "Council of Ephesus (A.D. 431)".

- ^ Vested angels: eucharistic allusions in early Netherlandish paintings by Maurice B. McNamee 1998 ISBN 978-9042900073 pp. 22–32

- ^ Gospel figures in art by Stefano Zuffi 2003 ISBN 978-0892367276 p. 252

- ^ Experiencing art around us by Thomas Buser 2005 ISBN 978-0534641146 pp. 382–83

- ^ Tintoretto: Tradition and Identity by Tom Nichols 2004 ISBN 1861891202 p. 234

- ^ The mathematics of harmony by Alexey Stakhov, Scott Olsen 2009 ISBN 978-9812775825 pp. 177–78

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Last Supper. |

- Mershman, Francis (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Last Supper" on Encyclopædia Britannica Online.