John Wesley

John Wesley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 June [O.S. 17 June] 1703 |

| Died | 2 March 1791 (aged 87) London, England |

| Nationality | British (English until 1707) |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford and Lincoln College, Oxford |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | Mary Vazeille (m. 1751; separated 1758) |

| Parent(s) | Samuel and Susanna Wesley |

| Relatives |

|

| Religion | Christian (Anglican / Methodist) |

| Church | Church of England |

| Ordained | 1725 |

| Writings | Articles of Religion |

Offices held | |

| Theological work | |

| Language | English |

| Tradition or movement | Methodism, Arminianism |

| Notable ideas | Imparted righteousness, Wesleyan Quadrilateral, Second work of grace |

| Signature | |

John Wesley (/ˈwɛsli/;[1] 28 June [O.S. 17 June] 1703 – 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, theologian and evangelist who was a leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies he founded became the dominant form of the independent Methodist movement that continues to this day.

Educated at Charterhouse and Christ Church, Oxford, Wesley was elected a fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford in 1726 and ordained as an Anglican priest two years later. He led the "Holy Club", a society formed for the purpose of the study and the pursuit of a devout Christian life; it had been founded by his brother, Charles, and counted George Whitefield among its members. After an unsuccessful ministry of two years at Savannah, serving at Christ Church, in the Georgia Colony, Wesley returned to London and joined a religious society led by Moravian Christians. On 24 May 1738, he experienced what has come to be called his evangelical conversion, when he felt his "heart strangely warmed". He subsequently left the Moravians, beginning his own ministry.

A key step in the development of Wesley's ministry was, like Whitefield, to travel and preach outdoors. In contrast to Whitefield's Calvinism, Wesley embraced Arminian doctrines. Moving across Great Britain and Ireland, he helped form and organize small Christian groups that developed intensive and personal accountability, discipleship and religious instruction. He appointed itinerant, unordained evangelists to care for these groups of people. Under Wesley's direction, Methodists became leaders in many social issues of the day, including prison reform and the abolition of slavery.

Although he was not a systematic theologian, Wesley argued for the notion of Christian perfection and against Calvinism—and, in particular, against its doctrine of predestination. His evangelicalism, firmly grounded in sacramental theology, maintained that means of grace sometimes had a role in sanctification of the believer; however, he taught that it was by faith a believer was transformed into the likeness of Christ. He held that, in this life, Christians could achieve a state where the love of God "reigned supreme in their hearts", giving them not only outward but inward holiness. Wesley's teachings, collectively known as Wesleyan theology, continue to inform the doctrine of the Methodist churches.

Throughout his life, Wesley remained within the established Church of England, insisting that the Methodist movement lay well within its tradition.[2] In his early ministry, Wesley was barred from preaching in many parish churches and the Methodists were persecuted; he later became widely respected and, by the end of his life, had been described as "the best-loved man in England".[3]

Early life[edit]

John Wesley was born in 1703 in Epworth, 23 miles (37 km) north-west of Lincoln, as the fifteenth child of Samuel Wesley and his wife Susanna Wesley (née Annesley).[4] Samuel Wesley was a graduate of the University of Oxford and a poet who, from 1696, was rector of Epworth. He married Susanna, the twenty-fifth child of Samuel Annesley, a dissenting minister, in 1689. Ultimately, she bore nineteen children, of which nine lived beyond infancy. She and Samuel Wesley had become members of the Church of England as young adults.[5]

As in many families at the time, Wesley's parents gave their children their early education. Each child, including the girls, was taught to read as soon as they could walk and talk. They were expected to become proficient in Latin and Greek and to have learned major portions of the New Testament by heart. Susanna Wesley examined each child before the midday meal and before evening prayers. The children were not allowed to eat between meals and were interviewed singly by their mother one evening each week for the purpose of intensive spiritual instruction. In 1714, at age 11, Wesley was sent to the Charterhouse School in London (under the mastership of John King from 1715), where he lived the studious, methodical and, for a while, religious life in which he had been trained at home.[6]

Apart from his disciplined upbringing, a rectory fire which occurred on 9 February 1709, when Wesley was five years old, left an indelible impression. Some time after 11:00 pm, the rectory roof caught on fire. Sparks falling on the children's beds and cries of "fire" from the street roused the Wesleys who managed to shepherd all their children out of the house except for John who was left stranded on an upper floor.[7] With stairs aflame and the roof about to collapse, Wesley was lifted out of a window by a parishioner standing on another man's shoulders. Wesley later used the phrase, "a brand plucked out of the fire", quoting Zechariah 3:2, to describe the incident.[7] This childhood deliverance subsequently became part of the Wesley legend, attesting to his special destiny and extraordinary work.

Education[edit]

In June 1720, Wesley entered Christ Church, Oxford. After graduating in 1724, Wesley stayed on at Christ Church to study for his master's degree.[8]

He was ordained a deacon on 25 September 1725—holy orders being a necessary step toward becoming a fellow and tutor at the university.[9] On 17 March 1726, Wesley was unanimously elected a fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford. This carried with it the right to a room at the college and regular salary.[10] While continuing his studies, he taught Greek and philosophy, lectured on the New Testament and moderated daily disputations at the university.[10] However, a call to ministry intruded upon his academic career. In August 1727, after completing his master's degree, Wesley returned to Epworth. His father had requested his assistance in serving the neighbouring cure of Wroot. Ordained a priest on 22 September 1728,[9] Wesley served as a parish curate for two years.[11]

In the year of his ordination he read Thomas à Kempis and Jeremy Taylor, showed his interest in mysticism,[12] and began to seek the religious truths which underlay the great revival of the 18th century. The reading of William Law's Christian Perfection and A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life gave him, he said, a more sublime view of the law of God; and he resolved to keep it, inwardly and outwardly, as sacredly as possible, believing that in obedience he would find salvation.[13] He pursued a rigidly methodical and abstemious life, studied the Scriptures, and performed his religious duties diligently, depriving himself so that he would have alms to give. He began to seek after holiness of heart and life.[13]

Wesley returned to Oxford in November 1729 at the request of the Rector of Lincoln College and to maintain his status as junior fellow.[14]

Holy Club[edit]

During Wesley's absence, his younger brother Charles (1707–88) matriculated at Christ Church. Along with two fellow students, he formed a small club for the purpose of study and the pursuit of a devout Christian life.[14] On Wesley's return, he became the leader of the group which increased somewhat in number and greatly in commitment. The group met daily from six until nine for prayer, psalms, and reading of the Greek New Testament. They prayed every waking hour for several minutes and each day for a special virtue. While the church's prescribed attendance was only three times a year, they took Communion every Sunday. They fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays until three o'clock as was commonly observed in the ancient church.[citation needed] In 1730, the group began the practice of visiting prisoners in gaol. They preached, educated, and relieved gaoled debtors whenever possible, and cared for the sick.[15]

Given the low ebb of spirituality in Oxford at that time, it was not surprising that Wesley's group provoked a negative reaction. They were considered to be religious "enthusiasts", which in the context of the time meant religious fanatics. University wits styled them the "Holy Club", a title of derision. Currents of opposition became a furore following the mental breakdown and death of a group member, William Morgan.[16] In response to the charge that "rigorous fasting" had hastened his death, Wesley noted that Morgan had left off fasting a year and a half since. In the same letter, which was widely circulated, Wesley referred to the name "Methodist" with which "some of our neighbors are pleased to compliment us."[17] That name was used by an anonymous author in a published pamphlet (1732) describing Wesley and his group, "The Oxford Methodists".[18]

For all of his outward piety, Wesley sought to cultivate his inner holiness or at least his sincerity as evidence of being a true Christian. A list of "General Questions" which he developed in 1730 evolved into an elaborate grid by 1734 in which he recorded his daily activities hour-by-hour, resolutions he had broken or kept, and ranked his hourly "temper of devotion" on a scale of 1 to 9. Wesley also regarded the contempt with which he and his group were held to be a mark of a true Christian. As he put it in a letter to his father, "Till he be thus contemned, no man is in a state of salvation."[19]

Journey to Savannah, Georgia[edit]

On 14 October 1735, Wesley and his brother Charles sailed on The Simmonds from Gravesend in Kent for Savannah in the Province of Georgia in the American colonies at the request of James Oglethorpe, who had founded the colony in 1733 on behalf of the Trustees for the Establishment of the Colony of Georgia in America. Oglethorpe wanted Wesley to be the minister of the newly formed Savannah parish, a new town laid out in accordance with the famous Oglethorpe Plan.[20]

It was on the voyage to the colonies that the Wesleys first came into contact with Moravian settlers. Wesley was influenced by their deep faith and spirituality rooted in pietism. At one point in the voyage a storm came up and broke the mast off the ship. While the English panicked, the Moravians calmly sang hymns and prayed. This experience led Wesley to believe that the Moravians possessed an inner strength which he lacked.[20] The deeply personal religion that the Moravian pietists practised heavily influenced Wesley's theology of Methodism.[20]

Wesley arrived in the colony in February 1736. He approached the Georgia mission as a High churchman, seeing it as an opportunity to revive "primitive Christianity" in a primitive environment. Although his primary goal was to evangelize the Native Americans, a shortage of clergy in the colony largely limited his ministry to European settlers in Savannah. While his ministry has often been judged to have been a failure in comparison to his later success as a leader in the Evangelical Revival, Wesley gathered around him a group of devoted Christians who met in a number of small group religious societies. At the same time, attendance at church services and Communion increased over the course of nearly two years in which he served as Christ Church's parish priest.[citation needed]

Nonetheless, Wesley's High Church ministry was controversial among the colonists and it ended in disappointment after Wesley fell in love with a young woman named Sophia Hopkey. He hesitated to marry her because he felt that his first priority in Georgia was to be a missionary to the Indigenous Americans, and he was interested in the practice of clerical celibacy within the early Christianity.[21] Following her marriage to William Williamson, Wesley believed Sophia's former zeal for practising the Christian faith declined. In strictly applying the rubrics of the Book of Common Prayer, Wesley denied her Communion after she failed to signify to him in advance her intention of taking it. As a result, legal proceedings against him ensued in which a clear resolution seemed unlikely. In December 1737, Wesley fled the colony and returned to England.[22]

It has been widely recognised that one of the most significant accomplishments of Wesley's Georgia mission was his publication of a Collection of Psalms and Hymns. The Collection was the first Anglican hymnal published in America, and the first of many hymn-books Wesley published. It included five hymns he translated from German.[23]

Wesley's "Aldersgate experience"[edit]

Wesley returned to England depressed and beaten. It was at this point that he turned to the Moravians. Both he and Charles received counsel from the young Moravian missionary Peter Boehler, who was temporarily in England awaiting permission to depart for Georgia himself. Wesley's noted "Aldersgate experience" of 24 May 1738, at a Moravian meeting in Aldersgate Street, London, in which he heard a reading of Martin Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans, revolutionised the character and method of his ministry.[24] The previous week he had been highly impressed by the sermon of John Heylyn, whom he was assisting in the service at St Mary le Strand. Earlier that day, he had heard the choir at St Paul's Cathedral singing Psalm 130, where the Psalmist calls to God "Out of the depths."[25]

But it was still a depressed Wesley who attended a service on the evening of 24 May. Wesley recounted his Aldersgate experience in his journal:

"In the evening I went very unwillingly to a society in Aldersgate Street, where one was reading Luther's Preface to the Epistle to the Romans. About a quarter before nine, while he was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death."[26][27]

A few weeks later, Wesley preached a sermon on the doctrine of personal salvation by faith,[28] which was followed by another, on God's grace "free in all, and free for all."[29] Considered a pivotal moment, Daniel L. Burnett writes: "The significance of Wesley's Aldersgate Experience is monumental … Without it the names of Wesley and Methodism would likely be nothing more than obscure footnotes in the pages of church history."[30] Burnett describes this event Wesley's "Evangelical Conversion".[31] It is commemorated in Methodist churches as Aldersgate Day.[32]

After Aldersgate: Working with the Moravians[edit]

Wesley allied himself with the Moravian society in Fetter Lane. In 1738 he went to Herrnhut, the Moravian headquarters in Germany, to study.[33] On his return to England, Wesley drew up rules for the "bands" into which the Fetter Lane Society was divided and published a collection of hymns for them.[34] He met frequently with this and other religious societies in London but did not preach often in 1738, because most of the parish churches were closed to him.[35]

Wesley's Oxford friend, the evangelist George Whitefield, was also excluded from the churches of Bristol upon his return from America. Going to the neighbouring village of Kingswood, in February 1739, Whitefield preached in the open air to a company of miners.[36] Later he preached in Whitefield's Tabernacle. Wesley hesitated to accept Whitefield's call to copy this bold step. Overcoming his scruples, he preached the first time at Whitefield's invitation sermon in the open air, near Bristol, in April 1739. Wesley wrote,

I could scarce reconcile myself to this strange way of preaching in the fields, of which he [Whitefield] set me an example on Sunday; having been all my life till very lately so tenacious of every point relating to decency and order, that I should have thought the saving of souls almost a sin if it had not been done in a church.[37]

Wesley was unhappy about the idea of field preaching as he believed Anglican liturgy had much to offer in its practice. Earlier in his life he would have thought that such a method of saving souls was "almost a sin."[38] He recognised the open-air services were successful in reaching men and women who would not enter most churches. From then on he took the opportunities to preach wherever an assembly could be brought together, more than once using his father's tombstone at Epworth as a pulpit.[39][40] Wesley continued for fifty years—entering churches when he was invited, and taking his stand in the fields, in halls, cottages, and chapels, when the churches would not receive him.[40]

Late in 1739 Wesley broke with the Moravians in London. Wesley had helped them organise the Fetter Lane Society, and those converted by his preaching and that of his brother and Whitefield had become members of their bands. But he believed they fell into heresy by supporting quietism, so he decided to form his own followers into a separate society.[41] "Thus," he wrote, "without any previous plan, began the Methodist Society in England."[42] He soon formed similar societies in Bristol and Kingswood, and Wesley and his friends made converts wherever they went.

Persecutions and lay preaching[edit]

From 1739 onward, Wesley and the Methodists were persecuted by clergy and magistrates for various reasons.[43] Though Wesley had been ordained an Anglican priest, many other Methodist leaders had not received ordination. And for his own part, Wesley flouted many regulations of the Church of England concerning parish boundaries and who had authority to preach.[44] This was seen as a social threat that disregarded institutions. Clergy attacked them in sermons and in print, and at times mobs attacked them. Wesley and his followers continued to work among the neglected and needy. They were denounced as promulgators of strange doctrines, fomenters of religious disturbances; as blind fanatics, leading people astray, claiming miraculous gifts, attacking the clergy of the Church of England, and trying to re-establish Catholicism.[44]

Wesley felt that the church failed to call sinners to repentance, that many of the clergy were corrupt, and that people were perishing in their sins. He believed he was commissioned by God to bring about revival in the church, and no opposition, persecution, or obstacles could prevail against the divine urgency and authority of this commission. The prejudices of his high-church training, his strict notions of the methods and proprieties of public worship, his views of the apostolic succession and the prerogatives of the priest, even his most cherished convictions, were not allowed to stand in the way.[45]

Seeing that he and the few clergy co-operating with him could not do the work that needed to be done, Wesley was led, as early as 1739, to approve local preachers. He evaluated and approved men who were not ordained by the Anglican Church to preach and do pastoral work. This expansion of lay preachers was one of the keys of the growth of Methodism.[46]

Chapels and organisations[edit]

As his societies needed houses to worship in, Wesley began to provide chapels, first in Bristol at the New Room,[47] then in London (first The Foundery and then Wesley's Chapel) and elsewhere. The Foundery was an early chapel used by Wesley.[48] The location of the Foundery is shown on an 18th-century map, where it rests between Tabernacle Street and Worship Street in the Moorfields area of London. When the Wesleys spotted the building atop Windmill Hill, north of Finsbury Fields, the structure which previously cast brass guns and mortars for the Royal Ordnance had been sitting vacant for 23 years; it had been abandoned because of an explosion on 10 May 1716.[49]

The Bristol chapel (built in 1739) was at first in the hands of trustees. A large debt was contracted, and Wesley's friends urged him to keep it under his own control, so the deed was cancelled and he became sole trustee.[50] Following this precedent, all Methodist chapels were committed in trust to him until by a "deed of declaration", all his interests in them were transferred to a body of preachers called the "Legal Hundred".[51]

When disorder arose among some members of the societies, Wesley adopted giving tickets to members, with their names written by his own hand. These were renewed every three months. Those deemed unworthy did not receive new tickets and dropped out of the society without disturbance. The tickets were regarded as commendatory letters.[52]

When the debt on a chapel became a burden, it was proposed that one in 12 members should collect offerings regularly from the 11 allotted to him. Out of this grew the Methodist class-meeting system in 1742. To keep the disorderly out of the societies, Wesley established a probationary system. He undertook to visit each society regularly in what became the quarterly visitation, or conference. As the number of societies increased, Wesley could not keep personal contact, so in 1743 he drew up a set of "General Rules" for the "United Societies". [53] These were the nucleus of the Methodist Discipline, still the basis.

Wesley laid the foundations of what now constitutes the organisation of the Methodist Church. Over time, a shifting pattern of societies, circuits, quarterly meetings, annual Conferences, classes, bands, and select societies took shape.[53] At the local level, there were numerous societies of different sizes which were grouped into circuits to which travelling preachers were appointed for two-year periods. Circuit officials met quarterly under a senior travelling preacher or "assistant." Conferences with Wesley, travelling preachers and others were convened annually for the purpose of co-ordinating doctrine and discipline for the entire connection. Classes of a dozen or so society members under a leader met weekly for spiritual fellowship and guidance. In early years, there were "bands" of the spiritually gifted who consciously pursued perfection. Those who were regarded to have achieved it were grouped in select societies or bands. In 1744, there were 77 such members. There also was a category of penitents which consisted of backsliders.[53]

As the number of preachers and preaching-places increased, doctrinal and administrative matters needed to be discussed; so John and Charles Wesley, along with four other clergy and four lay preachers, met for consultation in London in 1744. This was the first Methodist conference; subsequently, the conference (with Wesley as its president) became the ruling body of the Methodist movement.[54] Two years later, to help preachers work more systematically and societies receive services more regularly, Wesley appointed "helpers" to definitive circuits. Each circuit included at least 30 appointments a month. Believing that the preacher's efficiency was promoted by his being changed from one circuit to another every year or two, Wesley established the "itinerancy" and insisted that his preachers submit to its rules.[55]

John Wesley had strong links with the North West of England, visiting Manchester on at least fifteen occasions between 1733 and 1790. In 1733 and 1738 he preached at St Ann's Church and Salford Chapel, meeting with his friend John Clayton. In 1781 Wesley opened the Chapel on Oldham Street – part of the Manchester and Salford Wesleyan Methodist Mission,[56] now the site of Manchester's Methodist Central Hall.[57]

Following an illness in 1748 John Wesley was nursed by a classleader and housekeeper, Grace Murray, at an orphan house in Newcastle. Taken with Grace, he invited her to travel with him to Ireland in 1749 where he believed them to be betrothed though they were never married. It has been suggested that his brother Charles Wesley objected to the engagement,[58] though this is disputed. Subsequently, Grace married John Bennett, a preacher.[59]

Ordination of ministers[edit]

As the societies multiplied, they adopted the elements of an ecclesiastical system. The divide between Wesley and the Church of England widened. The question of division from the Church of England was urged by some of his preachers and societies, but most strenuously opposed by his brother Charles. Wesley refused to leave the Church of England, believing that Anglicanism was "with all her blemishes, [...] nearer the Scriptural plans than any other in Europe".[2] In 1745 Wesley wrote that he would make any concession which his conscience permitted, to live in peace with the clergy. He could not give up the doctrine of an inward and present salvation by faith itself; he would not stop preaching, nor dissolve the societies, nor end preaching by lay members. As a cleric of the established church he had no plans to go further.[citation needed]

When, in 1746, Wesley read Lord King's account of the primitive church, he became convinced that apostolic succession could be transmitted through not only bishops, but also priests. He wrote that he was "a scriptural episkopos as much as many men in England." Although he believed in apostolic succession, he also once called the idea of uninterrupted succession a "fable".[60]

Many years later, Edward Stillingfleet's Irenicon led him to decide that ordination (and holy orders) could be valid when performed by a presbyter (priest) rather than a bishop. Nevertheless, some believe that Wesley was secretly consecrated a bishop in 1763 by Erasmus of Arcadia,[61] and that Wesley could not openly announce his episcopal consecration without incurring the penalty of the Præmunire Act.[62]

In 1784, he believed he could no longer wait for the Bishop of London to ordain someone for the American Methodists, who were without the sacraments after the American War of Independence.[63] The Church of England had been disestablished in the United States, where it had been the state church in most of the southern colonies. The Church of England had not yet appointed a United States bishop to what would become the Protestant Episcopal Church in America. Wesley ordained Thomas Coke as superintendent[64] of Methodists in the United States by the laying on of hands, although Coke was already a priest in the Church of England. He also ordained Richard Whatcoat and Thomas Vasey as presbyters. Whatcoat and Vasey sailed to America with Coke. Wesley intended that Coke and Francis Asbury (whom Coke ordained as superintendent by direction of Wesley) should ordain others in the newly founded Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States. In 1787, Coke and Asbury persuaded the American Methodists to refer to them as bishops rather than superintendents,[65] overruling Wesley's objections to the change.[66]

His brother, Charles, was alarmed by the ordinations and Wesley's evolving view of the matter. He begged Wesley to stop before he had "quite broken down the bridge" and not embitter his [Charles'] last moments on earth, nor "leave an indelible blot on our memory."[25] Wesley replied that he had not separated from the church, nor did he intend to, but he must and would save as many souls as he could while alive, "without being careful about what may possibly be when I die."[67] Although Wesley rejoiced that the Methodists in America were free, he advised his English followers to remain in the established church and he himself died within it.

Doctrines, theology and advocacy[edit]

The 20th-century Wesley scholar Albert Outler argued in his introduction to the 1964 collection John Wesley that Wesley developed his theology by using a method that Outler termed the Wesleyan Quadrilateral.[68] In this method, Wesley believed that the living core of Christianity was revealed in Scripture; and the Bible was the sole foundational source of theological development. The centrality of Scripture was so important for Wesley that he called himself "a man of one book"[69]—meaning the Bible—although he was well-read for his day. However, he believed that doctrine had to be in keeping with Christian orthodox tradition. So, tradition was considered the second aspect of the Quadrilateral.[68]

Wesley contended that a part of the theological method would involve experiential faith. In other words, truth would be vivified in personal experience of Christians (overall, not individually), if it were really truth. And every doctrine must be able to be defended rationally. He did not divorce faith from reason. Tradition, experience and reason, however, were subject always to Scripture, Wesley argued, because only there is the Word of God revealed "so far as it is necessary for our salvation."[70]

The doctrines which Wesley emphasised in his sermons and writings are prevenient grace, present personal salvation by faith, the witness of the Spirit, and sanctification.[71] Prevenient grace was the theological underpinning of his belief that all persons were capable of being saved by faith in Christ. Unlike the Calvinists of his day, Wesley did not believe in predestination, that is, that some persons had been elected by God for salvation and others for damnation. He understood that Christian orthodoxy insisted that salvation was only possible by the sovereign grace of God. He expressed his understanding of humanity's relationship to God as utter dependence upon God's grace. God was at work to enable all people to be capable of coming to faith by empowering humans to have actual existential freedom of response to God.

Wesley defined the witness of the Spirit as: "an inward impression on the soul of believers, whereby the Spirit of God directly testifies to their spirit that they are the children of God."[72] He based this doctrine upon certain Biblical passages (see Romans 8:15–16 as an example). This doctrine was closely related to his belief that salvation had to be "personal." In his view, a person must ultimately believe the Good News for himself or herself; no one could be in relation to God for another.

Sanctification he described in 1790 as the "grand depositum which God has lodged with the people called 'Methodists'."[73] Wesley taught that sanctification was obtainable after justification by faith, between justification and death. He did not contend for "sinless perfection"; rather, he contended that a Christian could be made "perfect in love". (Wesley studied Eastern Orthodoxy and embraced particularly the doctrine of Theosis).[74] This love would mean, first of all, that a believer's motives, rather than being self-centred, would be guided by the deep desire to please God. One would be able to keep from committing what Wesley called, "sin rightly so-called." By this he meant a conscious or intentional breach of God's will or laws. A person could still be able to sin, but intentional or wilful sin could be avoided.[73]

Secondly, to be made perfect in love meant, for Wesley, that a Christian could live with a primary guiding regard for others and their welfare. He based this on Christ's quote that the second great command is "to love your neighbour as you love yourself." In his view, this orientation would cause a person to avoid any number of sins against his neighbour. This love, plus the love for God that could be the central focus of a person's faith, would be what Wesley referred to as "a fulfilment of the law of Christ."

Advocacy of Arminianism[edit]

Wesley entered controversies as he tried to enlarge church practice. The most notable of his controversies was that on Calvinism. His father was of the Arminian school in the church. Wesley came to his own conclusions while in college and expressed himself strongly against the doctrines of Calvinistic election and reprobation. His system of thought has become known as Wesleyan Arminianism, the foundations of which were laid by Wesley and fellow preacher John William Fletcher.

Whitefield inclined to Calvinism. In his first tour in America, he embraced the views of the New England School of Calvinism. When in 1739 Wesley preached a sermon on Freedom of Grace, attacking the Calvinistic understanding of predestination as blasphemous, as it represented "God as worse than the devil," Whitefield asked him not to repeat or publish the discourse, as he did not want a dispute. Wesley published his sermon anyway. Whitefield was one of many who responded. The two men separated their practice in 1741. Wesley wrote that those who held to unlimited atonement did not desire separation, but "those who held 'particular redemption' would not hear of any accommodation."[75]

Whitefield, Harris, Cennick, and others, became the founders of Calvinistic Methodism. Whitefield and Wesley, however, were soon back on friendly terms, and their friendship remained unbroken although they travelled different paths. When someone asked Whitefield if he thought he would see Wesley in heaven, Whitefield replied, "I fear not, for he will be so near the eternal throne and we at such a distance, we shall hardly get sight of him."[76]

In 1770, the controversy broke out anew with violence and bitterness, as people's view of God related to their views of men and their possibilities. Augustus Toplady, Rowland, Richard Hill and others were engaged on one side, while Wesley and Fletcher stood on the other. Toplady was editor of The Gospel Magazine, which had articles covering the controversy.

In 1778, Wesley began the publication of The Arminian Magazine, not, he said, to convince Calvinists, but to preserve Methodists. He wanted to teach the truth that "God willeth all men to be saved."[77] A "lasting peace" could be secured in no other way.

Support for abolitionism[edit]

Later in his ministry, Wesley was a keen abolitionist,[78][79] speaking out and writing against the slave trade. Wesley denounced slavery as "the sum of all villainies," and detailed its abuses.[80] He published a pamphlet on slavery, titled Thoughts Upon Slavery, in 1774.[80] He wrote, "Liberty is the right of every human creature, as soon as he breathes the vital air; and no human law can deprive him of that right which he derives from the law of nature".[81] Wesley influenced George Whitefield to journey to the colonies, spurring the transatlantic debate on slavery.[82] Wesley was a friend and mentor to John Newton and William Wilberforce, who were also influential in the abolition of slavery in Britain.[83]

Support for women preachers[edit]

Women had an active role in Wesley's Methodism, and were encouraged to lead classes. In 1761, he informally allowed Sarah Crosby, one of his converts and a class leader, to preach.[84] On an occasion where over 200 people attended a class she was meant to teach, Crosby felt as though she could not fulfill her duties as a class leader given the large crowd, and decided to preach instead.[85][86] She wrote to Wesley to seek his advice and forgiveness.[87] He let Crosby to continue her preaching so long as she refrained from as many of the mannerisms of preaching as she could.[88] Between 1761 and 1771, Wesley wrote detailed instructions to Crosby and others, with specifics on what styles of preaching they could use. For instance, in 1769, Wesley allowed Crosby to give exhortations.[89]

In the summer of 1771, Mary Bosanquet wrote to John Wesley to defend hers and Sarah Crosby's work preaching and leading classes at her orphanage, Cross Hall.[90][91] Bosanquet's letter is considered to be the first full and true defense of women's preaching in Methodism.[90] Her argument was that women should be able to preach when they experienced an 'extraordinary call,' or when given permission from God.[90][92] Wesley accepted Bosanquet's argument, and formally began to allow women to preach in Methodism in 1771.[93][92]

Personality and activities[edit]

Wesley travelled widely, generally on horseback, preaching two or three times each day. Stephen Tomkins writes that "[Wesley] rode 250,000 miles, gave away 30,000 pounds, ... and preached more than 40,000 sermons... "[94] He formed societies, opened chapels, examined and commissioned preachers, administered aid charities, prescribed for the sick, helped to pioneer the use of electric shock for the treatment of illness,[95] superintended schools and orphanages and published his sermons.

Wesley practised a vegetarian diet and in later life abstained from wine for health reasons.[96] Wesley warned against the dangers of alcohol abuse in his famous sermon, The Use of Money,[97] and in his letter to an alcoholic.[98] In his sermon, On Public Diversions, Wesley says: "You see the wine when it sparkles in the cup, and are going to drink of it. I tell you there is poison in it! and, therefore, beg you to throw it away".[99] However, other materials show less concern with consumption of alcohol.[100] He encourages experimentation in the role of hops in the brewing of beer in a letter which dates from 1789.[101] Despite this, some Methodist churches became pioneers in the teetotal Temperance movement of the 19th and 20th centuries, and later it became de rigueur in all.

After attending a performance in Bristol Cathedral in 1758, Wesley said: "I went to the cathedral to hear Mr. Handel's Messiah. I doubt if that congregation was ever so serious at a sermon as they were during this performance. In many places, especially several of the choruses, it exceeded my expectation."[102]

He is described as below medium height, well proportioned, strong, with a bright eye, a clear complexion, and a saintly, intellectual face.[103] Though Wesley favoured celibacy rather than marital bond,[104][105] he married very unhappily at the age of 48 to a widow, Mary Vazeille, described as "a well-to-do widow and mother of four children."[106] The couple had no children. Vazeille left him 15 years later. John Singleton writes: "By 1758 she had left him – unable to cope, it is said, with the competition for his time and devotion presented by the ever-burgeoning Methodist movement. Molly, as she was known, was to return and leave him again on several occasions before their final separation."[106] Wesley wryly reported in his journal, "I did not forsake her, I did not dismiss her, I will not recall her."

In 1770, at the death of George Whitefield, Wesley wrote a memorial sermon which praised Whitefield's admirable qualities and acknowledged the two men's differences: "There are many doctrines of a less essential nature ... In these we may think and let think; we may 'agree to disagree.' But, meantime, let us hold fast the essentials..."[107] Wesley may have been the first to use "agree to disagree" in print[108] — in the modern sense of tolerating differences — though he himself attributed the saying to Whitefield, and it had appeared in other senses previously.

Death[edit]

Wesley's health declined sharply towards the end of his life and he ceased preaching. On 28 June 1790, less than a year before his death, he wrote:

This day I enter into my eighty-eighth year. For above eighty-six years, I found none of the infirmities of old age: my eyes did not wax dim, neither was my natural strength abated. But last August, I found almost a sudden change. My eyes were so dim that no glasses would help me. My strength likewise now quite forsook me and probably will not return in this world.[109]

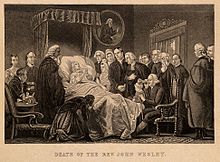

Wesley died on 2 March 1791, at the age of 87. As he lay dying, his friends gathered around him, Wesley grasped their hands and said repeatedly, "Farewell, farewell." At the end, he said, "The best of all is, God is with us", lifted his arms and raised his feeble voice again, repeating the words, "The best of all is, God is with us."[110] He was entombed at his chapel on City Road, London.

Because of his charitable nature he died poor, leaving as the result of his life's work 135,000 members and 541 itinerant preachers under the name "Methodist". It has been said that "when John Wesley was carried to his grave, he left behind him a good library of books, a well-worn clergyman's gown" and the Methodist Church.[110]

Literary work[edit]

Wesley wrote, edited or abridged some 400 publications. As well as theology he wrote about music, marriage, medicine, abolitionism and politics.[111] Wesley was a logical thinker and expressed himself clearly, concisely and forcefully in writing. His written sermons are characterised by spiritual earnestness and simplicity. They are doctrinal but not dogmatic. His Forty-Four Sermons and the Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament (1755) are Methodist doctrinal standards.[112] Wesley was a fluent, powerful and effective preacher; he usually preached spontaneously and briefly, though occasionally at great length.

In his Christian Library (1750), he writes about mystics such as Macarius of Egypt, Ephrem the Syrian, Madame Guyon, François Fénelon, Ignatius of Loyola, John of Ávila, Francis de Sales, Blaise Pascal, and Antoinette Bourignon. The work reflects the influence of Christian mysticism in Wesley's ministry from the beginning to the end,[12] although he ever rejected it after the failure in Georgia mission.[113]

Wesley's prose, Works were first collected by himself (32 vols., Bristol, 1771–74, frequently reprinted in editions varying greatly in the number of volumes). His chief prose works are a standard publication in seven octavo volumes of the Methodist Book Concern, New York. The Poetical Works of John and Charles, ed. G. Osborn, appeared in 13 vols., London, 1868–72.

In addition to his Sermons and Notes are his Journals (originally published in 20 parts, London, 1740–89; new ed. by N. Curnock containing notes from unpublished diaries, 6 vols., vols. i–ii, London and New York, 1909–11); The Doctrine of Original Sin (Bristol, 1757; in reply to Dr. John Taylor of Norwich); An Earnest Appeal to Men of Reason and Religion (originally published in three parts; 2nd ed., Bristol, 1743), an elaborate defence of Methodism, describing the evils of the times in society and the church; and a Plain Account of Christian Perfection (1766).

Wesley's Sunday Service[114] was an adaptation of the Book of Common Prayer for use by American Methodists.[115] In his Watch Night service, he made use of a pietist prayer now generally known as the Wesley Covenant Prayer, perhaps his most famous contribution to Christian liturgy. He was a noted hymn-writer, translator and compiler of a hymnal.[116]

Wesley also wrote on physics and medicine, such as in The Desideratum, subtitled Electricity made Plain and Useful by a Lover of Mankind and of Common Sense (1759).[117] and Primitive Physic, Or, An Easy and Natural Method of Curing Most Diseases.[118]

In spite of the proliferation of his literary output, Wesley was challenged for plagiarism for borrowing heavily from an essay by Samuel Johnson, publishing in March 1775. Initially denying the charge, Wesley later recanted and apologised officially.[119]

Commemoration and legacy[edit]

Wesley continues to be the primary theological influence on Methodists and Methodist-heritage groups the world over; the Methodist movement numbers 75 million adherents in more than 130 countries.[120] Wesleyan teachings also serve as a basis for the Holiness movement, which includes denominations like Free Methodist Church, the Church of the Nazarene, and several smaller groups, and from which Pentecostalism and parts of the Charismatic movement are offshoots.[121] Wesley's call to personal and social holiness continues to challenge Christians who attempt to discern what it means to participate in the Kingdom of God.

He is commemorated in the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on 2 March with his brother Charles. The Wesley brothers are also commemorated on 3 March in the Calendar of Saints of the Episcopal Church,[122] and on 24 May in the Anglican calendar.[123]

In 2002, Wesley was listed at number 50 on the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons, drawn from a poll of the British public.[124]

Wesley's house and chapel, which he built in 1778 on City Road in London, are still intact today and the chapel has a thriving congregation with regular services as well as the Museum of Methodism in the crypt.

Numerous schools, colleges, hospitals and other institutions are named after Wesley; additionally, many are named after Methodism. In 1831, Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, was the first institution of higher education in the United States to be named after Wesley. The now secular institution was founded as an all-male Methodist college. About 20 unrelated colleges and universities in the United States were subsequently named after him.[citation needed]

Statue of Wesley outside Wesley Church in Melbourne, Australia.

Display panel at Gwennap Pit, Cornwall, England.

Stained glass window at Lake Junaluska, NC

The Wesley Window at the World Methodist Museum, Lake Junaluska, NC

In film[edit]

In 1954, the Radio and Film Commission of the British Methodist Church, in co-operation with J. Arthur Rank, produced the film John Wesley. The film was a live-action re-telling of the story of the life of Wesley, with Leonard Sachs in the title role.

In 2009, a more ambitious feature film, Wesley, was released by Foundery Pictures, starring Burgess Jenkins as Wesley, with June Lockhart as Susanna, R. Keith Harris as Charles Wesley, and the Golden Globe winner Kevin McCarthy as Bishop Ryder. The film was directed by the award-winning film-maker John Jackman.[125]

In musical theatre[edit]

In 1976 the musical Ride! Ride!, composed by Penelope Thwaites AM and written by Alan Thornhill, premiered at the Westminster Theatre in London's West End. The piece is based on the true story of eighteen-year-old Martha Thompson's incarceration in Bedlam, an incident in Wesley's life. The premier ran for 76 performances.[126] Since then it has had more than 40 productions, both amateur and professional, including a 1999 concert version, issued on the Somm record label, with Keith Michell as Wesley.[127]

Works[edit]

- Wesley, John (1733). A collection of forms of prayer for every day in the week.

- Norris, John; Wesley, John (1734). A Treatise on Christian Prudence.

- Wesley, John (1743). An earnest appeal to men of reason and religion. Bristol: Printed by Felix Farley.

- Wesley, John (1744). Primitive Physic, Or, An Easy and Natural Method of Curing Most Diseases. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John; Farley, Felix (1749). A christian library. Bristol: Printed by Felix Farley.

- Wesley, John (1754). The New Testament, with explanatory notes. London: W. Nicholson.

- Wesley, John (1755). Explanatory Notes on the New Testament. Bristol: William Pine.

- Wesley, John (1757). The Doctrine of Original Sin. Bristol: William Pine. (in reply to Dr. John Taylor of Norwich)

- Wesley, John (1759). The Desideratum; or, Electricity Made Plain and Useful. London: Bailliere, Tindall, and Cox.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John (1763). A survey of the wisdom of God in the creation : or a compendium of natural philosophy. Bristol: William Pine.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John (1765). Explanatory Notes upon the Old Testament. Bristol: William Pine.

- Wesley, John (1766). A Plain Account of Christian Perfection. Bristol: Printed by William Pine.

- Wesley, John (1771–1774). Works. 32 volumes. Bristol: William Pine. (This edition has many errors.)

- Wesley, John (1809–1813). Works. 17 volumes. Joseph Benson. (This is better than the preceding, but is still very erroneus.)

- Wesley, John (1827). Works. 14 volumes. Thomas Jackson. (At present, the standard edition.)

- Wesley, John (1831). Works. 7 volumes. John Emory. (combining two volumes of the Jackson Edition into one. Containing two extra letters and more footnotes.)

- Wesley, John (1831). Works. 15 volumes. John Emory. (the Jackson Edition with an additional volume containing his Notes to the New Testament)

- Wesley, John; Wesley, Charles; Osborn, G. (1868–1871). The poetical works of John and Charles Wesley. London.

- Wesley, John (1739–1789). Journals. 20 parts. (originally published in 20 parts)

- Wesley, John (1909–1911). Journals. 6 volumes. Nehemiah Curnock. (containing notes from unpublished diaries)

See also[edit]

- List of Methodist theologians

- History of Christianity in Britain

- Wesley College, for educational institutions named after Wesley

Notes and references[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Wells 2008, Wesley. The founder of Methodism was actually /ˈwɛsli/, though often pronounced as /ˈwɛzli/

- ^ a b Thorsen 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Kiefer 2019.

- ^ BBC Humberside 2008.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2019.

- ^ Johnson 2002.

- ^ a b Wallace 1997.

- ^ Tomkins 2003, p. 22.

- ^ a b Young 2015, p. 61.

- ^ a b Tomkins 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Tomkins 2003, p. 23.

- ^ a b Wesley & Whaling 1981, p. 10.

- ^ a b Law 2009.

- ^ a b Tomkins 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Iovino 2016.

- ^ Tomkins 2003, p. 37.

- ^ Wesley 1931, letter 1732.

- ^ The Methodist Church 2011.

- ^ Wesley & Benson 1827.

- ^ a b c Ross & Stacey 1998.

- ^ Hodges 2014.

- ^ Bowman 2019.

- ^ Hammond 2014.

- ^ Hurst 1903, pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b Wesley 2000.

- ^ Dreyer 1999.

- ^ Christianity.com 2007.

- ^ Wesley & Jackson 1979, Sermon #1: Salvation By Faith.

- ^ Wesley & Jackson 1979, Sermon #128: Free Grace.

- ^ Burnett 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Burnett 2006, p. 36-37.

- ^ Waltz 1991.

- ^ Dose 2015.

- ^ Wesley & Emory 1831.

- ^ Green 2019.

- ^ LAMC 2019.

- ^ Buckley 1898.

- ^ Tomkins 2003, p. 69.

- ^ BBC 2011.

- ^ a b Brownlow 1859.

- ^ Smith 2010.

- ^ Oden 2013.

- ^ Tooley 2014.

- ^ a b Lane 2015.

- ^ Bowen 1901.

- ^ Burdon 2005.

- ^ The New Room Bristol 2017.

- ^ The Asbury Triptych 2019.

- ^ Tooley 1870.

- ^ Bates 1983.

- ^ Hurst 1903, Chapter XVIII – Setting His House in Order.

- ^ Parkinson 1898.

- ^ a b c Hurst 1903, Chapter IX – Society and Class.

- ^ Graves 2007.

- ^ Spiak 2011.

- ^ Hindle 1975.

- ^ Manchester City Council 2019.

- ^ Collins 2003.

- ^ Bunting 1940.

- ^ Holden 1870.

- ^ Wesleyan Methodist Magazine 1836. Mr. Wesley thus became a Bishop, and consecrated Dr. Coke, who united himself with ... who gave it under his own hand that Erasmus was Bishop of Arcadia, ...

- ^ Cooke 1896, p. 145. Dr. Peters was present at the interview, and went with and introduced Dr. Seabury to Mr. Wesley, who was so far satisfied that he would have been willingly consecrated by him in Mr. Wesley would have signed his letter of orders as bishop, which Mr. Wesley could not do without incurring the penalty of the Præmunire Act.

- ^ UMC of Indiana 2019.

- ^ Wesley 1915, p. 264. I have accordingly appointed Dr. Coke and Mr. Francis Asbury to be joint superintendents over our brethren in North America...

- ^ Lee 1810, p. 128. This was the first time that our superintendents ever gave themselves the title of Bishops in the minutes. They changed the title themselves without the consent of the conference; and at the next conference they asked the preachers if the word Bishop might stand in the minutes; seeing that it was a scripture name, and the meaning of the word Bishop, was the same with that of Superintendent. Some of the preachers opposed the alteration... but a majority of the preachers agreed to let the word Bishop remain.

- ^ Wesley 1915. How can you, how dare you, suffer yourself to be called Bishop? I shudder, I start at the very thought! Men may call me a knave or a fool, a rascal, a scoundrel, and I am content; but they shall never, by my consent, call me Bishop! For my sake, for God's sake, for Christ's sake, put a full end to this!

- ^ Wesley 1931, letter 1785b.

- ^ a b Mellor 2003.

- ^ Craik 1916.

- ^ Patterson 1984.

- ^ McDonald 2012.

- ^ Wesley & Outler 1984.

- ^ a b Miller 2012.

- ^ McCormick 1991.

- ^ Stevens 1858.

- ^ Wiersbe 1984.

- ^ Gunter 2011.

- ^ Carey 2002.

- ^ Carey 2003.

- ^ a b Wesley 1774.

- ^ Yrigoyen 1996.

- ^ Yoon 2012.

- ^ Valentine 1997.

- ^ English 1994.

- ^ Burge 1996.

- ^ Jensen 2013.

- ^ Lloyd 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Chilcote 1991.

- ^ Tucker & Liefeld 2010.

- ^ a b c Chilcote 1993, p. 78.

- ^ Burton 2008.

- ^ a b Lloyd 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Eason 2003.

- ^ Oakes 2004.

- ^ Johnstone 2000.

- ^ Preece 2008, p. 239. Thanks be to God, since the time I gave up flesh meals and wine I have been delivered from all physical ills.

- ^ Wesley & Jackson 1979, Sermon #50: The Use Of Money.

- ^ Anderson 2001.

- ^ Wesley & Jackson 1979, Sermon #140: On Public Diversions.

- ^ Wesley 1931, 1735, To his mother.

- ^ Wesley 1931, 1789, To the Printer of the 'Bristol Gazette'.

- ^ Wesley & Emory 1835.

- ^ Carroll 1953.

- ^ Coe 1996.

- ^ Lawrence 2011.

- ^ a b Busenitz 2013.

- ^ Wesley & Jackson 1979, Sermon #53: On The Death of The Rev. Mr. George Whitefield.

- ^ Martin 2019.

- ^ Williams 2012.

- ^ a b Hurst 1903, p. 298.

- ^ The Methodist Church 2019.

- ^ Methodist Church (Great Britain) 2019.

- ^ Heath 2010.

- ^ "A Methodist Model Of Worship: John Wesley's Sunday Service Part I". Worship Training. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ Tucker 1996.

- ^ Wesley 1779.

- ^ Wesley 1759. It is highly probable [Electricity]] is the general Instrument of all the Motion in the Universe.

- ^ Wesley 1744.

- ^ Abelove 1997.

- ^ Cracknell & White 2005, p. vii.

- ^ Dayton 1987.

- ^ Campbell 2019, p. 89.

- ^ Buchanan 2006, p. 470.

- ^ BBC 2002.

- ^ IMDb 2019.

- ^ The Guide to Musical Theatre 2014.

- ^ Thwaites 2000.

Sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- Bowen, William Abraham (1901). Why Two Episcopal Methodist Churches in the United States?: A Brief History Answering this Question for the Benefit of Epworth Leaguers and Other Young Methodists. Nashville, TN: Publishing house of the M.E. church.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buckley, James Monroe (1898). A History of Methodism in the United States. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 88–89. Retrieved 29 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buchanan, Colin (2006). Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism. Oxford: Scarecrow Press. p. 470. ISBN 978-0-8108-6506-8. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bunting, William Braylesford (1940). Chapel-en-le-Frith – Its History and its People (1st ed.). Manchester: Sherratt & Hughes. pp. 277–278.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burge, Janet (1996). Women Preachers in Community: Sarah Ryan, Sarah Crosby, Mary Bosanquet. [Peterborough]: Foundery Press. p. 9. ISBN 9781858520629.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burdon, Adrian (2005). Authority and order: John Wesley and his preachers. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7546-5454-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burnett, Daniel L. (2006). In the Shadow of Aldersgate: An Introduction to the Heritage and Faith of the Wesleyan Tradition. La Vergne: Wipf and Stock.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burton, Vicki Tolar (2008). Spiritual Literacy in John Wesley's Methodism: Reading, Writing, and Speaking to Believe. Waco,TX: Baylor University Press. p. 164. ISBN 9781602580237.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Ted A. (2019). Deeper Christian Faith, Revised Edition: A Re-Sounding. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-5326-5752-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carroll, H. K. (1953). "Wesley, John". The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. 12. Grand Rapids: Baker. p. 310.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chilcote, Paul Wesley (1993). She Offered Them Christ: The Legacy of Women Preachers in Early Methodism. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 1579106684.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chilcote, Paul Wesley (1991). John Wesley and the Women Preachers of Early Methodism. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press. pp. 121–122. ISBN 0810824140.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coe, Bufford W. (1996). John Wesley and Marriage. Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press. ISBN 0934223394.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Kenneth J (2003). John Wesley A Theological Journey. Nashville Tennessee: Abingdon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooke, R. J. (1896). The historic episcopate: a study of Anglican claims and Methodist orders. New York: Eaton & Mains.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cracknell, Kenneth; White, Susan J. (2005). An Introduction to World Methodism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81849-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Craik, Henry (1916). "John Wesley (1703–1791). A Man of One Book". English prose selections. 9. London: Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dayton, Donald W. (1987). Theological Roots of Pentecostalism. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Pub. ISBN 0-8010-4604-1. Retrieved 11 June 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dreyer, Frederick A. (1999). The Genesis of Methodism. Bethlehem, N.J.: Lehigh University Press. p. 27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eason, Andrew Mark (2003). Women in God's Army: Gender and Equality in the Early Salvation Army. Waterloo, Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780889208216.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gunter, W. Stephen (2011). An Annotated Content Index. The Arminian Magazine, Vols. 1–20 (1778–1797) (PDF). Duke Divinity School.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hammond, Geordan (2014). John Wesley in America: Restoring Primitive Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 106.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heath, Elaine A. (2010). Naked Faith: The Mystical Theology of Phoebe Palmer. Cambridge: James Clarke & Co. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0227903315.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hindle, Gordon Bradley (1975). Provision for the Relief of the Poor in Manchester, 1754–1826. Manchester: Manchester University Press for the Chetham Society. pp. 78–79.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holden, H. W. (1870). John Wesley in company with high churchmen. London: Church Press Co. pp. 57–59.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hurst, J. F. (1903). John Wesley the Methodist : a plain account of his life and work. New York: Methodist Book Concern.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jensen, Carolyn Passig (2013). The Spiritual Rhetoric of Early Methodist Women: Susanna Wesley, Sarah Crosby, Mary Bosanquet Fletcher, and Hester Rogers (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). [Norman, Oklahoma]: University of Oklahoma. p. 120.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnstone, Lucy (2000). Users and Abusers of Psychiatry: A Critical Look at Psychiatric Practice. London: Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 0-415-21155-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Law, William (2009). A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lawrence, Anna M. (2011). One Family Under God: Love, Belonging, and Authority in Early Transatlantic Methodism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 134–136. ISBN 978-0812204179.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Jesse (1810). A Short History of the Methodists in the United States of America. Baltimore: Magill and Clime.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lloyd, Jennifer M. (2009). Women and the Shaping of British Methodism: Persistent Preachers, 1807–1907. Oxford: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-84779-323-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McDonald, Calvin (2012). From the Coffin to the Cross: A Much Needed Awakening. Bloomington Drive: WestBow Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-4497-7791-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Methodist Church (Great Britain) (2019). The Constitutional Practice and Discipline of the Methodist Church. 2. London: Methodist Publishing. p. 499.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oden, Thomas C. (2013). Pastoral Theology. John Wesley's Teachings. 3. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0310587095.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patterson, Ronald (1984). The Book of Discipline of the United Methodist Church, 1984. Nashville, TN: United Methodist Publ. House. p. 77.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Preece, Rod (2008). Sins of the Flesh: A History of Ethical Vegetarian Thought. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-5849-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stevens, Abel (1858). The History of the Religious Movement of the Eighteenth Century, called Methodism. 1. London: Carlton & Porter. p. 155.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thorsen, Don (2005). The Wesleyan quadrilateral : scripture, tradition, reason & experience as a model of evangelical theology. Lexington, Ky: Emeth Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thwaites, Penelope (2000). Ride! Ride!. Surrey, England: Somm Recordings. OCLC 844535136.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomkins, Stephen (2003). John Wesley: A Biography. Oxford: Lion Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tooley, Mark (1870). Minutes of Proceedings of the Royal Artillery Institution. 6. Woolwich: Royal artillery institution. p. 48.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Ruth A.; Liefeld, Walter L. (2010). Daughters of the Church: Women and Ministry from New Testament Times to the Present. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. p. 241. ISBN 9780310877462.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Valentine, S. R. (1997). John Bennet & the Origins of Methodism and the Evangelical revival in England. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace, Charles Jr (1997). Susanna Wesley : the complete writings. New York: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waltz, Alan K. (1991). "Aldersgate". A dictionary for United Methodists. Nashville: Abingdon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wells, JC (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John (1779). A Collection of Hymns for the Use of the People called Methodists. London: Wesleyan Conference Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John (1931). The Letters of John Wesley. London: Epworth Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John (1774). Thoughts Upon Slavery. London: PRINTED: Re-printed in PHILADELPHIA, with notes, and sold by JOSEPH CRUKSHANK.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John; Jackson, Thomas (1979). The Works of John Wesley (1872). 1. Kansas City, Mo: Beacon Hill’s.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John (1915). Letters of John Wesley. New York: Hodder and Stoughton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John; Whaling, Frank (1981). John and Charles Wesley: Selected Prayers, Hymns, Journal Notes, Sermons, Letters and Treatises. New Jersey: Paulist Press. ISBN 0809123681.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John; Benson, Joseph (1827). The works of the Rev. John Wesley : in ten volumes. New York: J. & J. Harper. p. 108.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John (2000). "Talks with Bohler". Wesley's Journal. Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John; Emory, John (1831). "Wesley's Rules for Band-Societies". The Works of the Reverend John Wesley, A. M. 5. New York: B. Waugh and T. Mason. p. 192.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John; Outler, Albert C. (1984). The Works of John Wesley. 1. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. p. 296.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, John; Emory, John (1835). The Works of the Reverend John Wesley, A. M. 4. New York: B. Waugh and T. Mason. p. 7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesley, Charles (2000). John R. Tyson (ed.). Charles Wesley: A Reader. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-19-802102-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wesleyan Methodist Magazine (1836). Wesleyan-Methodist magazine: being a continuation of the Arminian or Methodist magazine first publ. by John Wesley. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiersbe, Warren W (1984). The Wycliffe handbook of preaching and preachers. Chicago: Moody Press. p. 255.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Francis (2015). Inferior Office: A History of Deacons in the Church of England. ISD LLC. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-227-90372-8. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yrigoyen, Charles (1996). "Wesley John, "Thoughts Upon Slavery"". John Wesley: Holiness of Heart and Life. New York: Mission Education and Cultivation Program Dept. for the Women's Division, General Board of Global Ministries, United Methodist Church.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Articles[edit]

- Abelove, Henry (1997). "John Wesley's plagiarism of Samuel Johnson and its contemporary reception". The Huntington Library Quarterly. 59 (1): 73–80.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Lesley G. (2001). "John Wesley and His Challenge to Alcoholism" (PDF). Wesley Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bates, E. Ralph (1983). "Wesley's Property Deed for Bath" (PDF). Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society. Wesley Historical Society. 44 (2): 25–35.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- BBC (2002). "BBC reveals 100 great British heroes". BBC News. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- BBC (2011). "Methodist Church". BBC. Retrieved 13 December 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- BBC Humberside (2008). "John Wesley at Epworth". BBC Humberside. Retrieved 16 January 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowman, John S. (2019). "John Wesley Trial: 1737 – Threats, Flight, And A New Church". Law Library – American Law and Legal Information. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brownlow, George Washington (1859). "John Wesley Preaching from His Father's Tomb at Epworth". Art UK. Retrieved 20 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Busenitz, Nathan (2013). "John Wesley's Failed Marriage". the Cripplegate. Retrieved 7 July 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carey, Brycchan (2003). "John Wesley's Thoughts Upon Slavery and the Language of the Heart" (PDF). The Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester. 85 (2–3): 269–284.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carey, Brycchan (2002). "John Wesley (1703–1791)". British Abolitionists. Retrieved 13 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christianity.com (2007). "John Wesley's Heart Strangely Warmed". Christianity.com. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dose, Kai (2015). "A Note on John Wesley's Visit to Herrnhut in 1738". Wesley and Methodist Studies. 7 (1): 117–120. doi:10.5325/weslmethstud.7.1.0117. JSTOR 10.5325/weslmethstud.7.1.0117.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- English, John C. (1994). "'Dear Sister': John Wesley and the Women of Early Methodism". Methodist History. 33 (1): 32.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Graves, Dan (2007). "1st Methodist Conference Convened in London". Christianity. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, Roger J. (2019). "1738 John & Charles Wesley Experience Conversions". Christianity Today. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hodges, Sam (2014). "Re-evaluating John Wesley's time in Georgia". United Methodist Church News.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- IMDb (2019). "Wesley (2009)". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 13 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Iovino, Joe (2016). "The method of early Methodism: The Oxford Holy Club". United Methodist Church. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson, Paul (2002). "Was there madness in his Methodism?". Telegraph. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kiefer, James (2019). "John & Charles Wesley: Renewers of the Church (3 mar 1791)". The Lectionary. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- LAMC (2019). "A brief history and the structure of Methodism". Launceston Area Methodist Churches. Retrieved 10 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lane, Mark H. (2015). "John Wesley Receives the Holy Spirit at Aldersgate" (PDF). Bible Numbers for Life. Retrieved 13 December 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manchester City Council (2019). "Stevenson Square Conservation Area: History". Manchester City Council. Manchester City Council. Retrieved 17 January 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, Gary (2019). "Agree to disagree". The Phrase Finder. Retrieved 13 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCormick, K. Steve (1991). "Theosis in Chrysostom and Wesley: An Eastern Paradigm of Faith and Love" (PDF). Wesleyan Theological Journal. Wesley Center for Applied Theology. 26: 38–103.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mellor, G. Howard (2003). "The Wesleyan Quadrilateral". Methodist Evangelicals Together. Retrieved 26 December 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Andrew (2012). "John Wesley's "Grand Depositum" and Nine Essentials from Primitive Methodism". Seedbed.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oakes, Edward T. (2004). "John Wesley: A Biography". First Things. Retrieved 13 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parkinson, F.M. (1898). "Class Tickets" (PDF). Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society. Wesley Historical Society. 1 (5): 129–137.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ratcliffe, Richard (2019). "The Family of John and Charles Wesley". My Wesleyan Methodists. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, Kathy W.; Stacey, Rosemary (1998). "John Wesley and Savannah". Savannah Images Project. Retrieved 18 September 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, James-Michael (2010). "Wesley's Doctrine of Christian Perfection" (PDF). Smith. Retrieved 20 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spiak, Jody (2011). "The Itinerant System: The Method(ists) Behind the Madness". UMC of Milton-Marlboro. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Asbury Triptych (2019). "John Wesley's Foundry Church". The Asbury Triptych. Retrieved 9 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Guide to Musical Theatre (2014). "Ride! Ride!". The Guide to Musical Theatre. Retrieved 13 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Methodist Church (2019). "History: Social Justice". Methodist Church in Britain. Retrieved 13 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Methodist Church (2011). "The Holy Club". The Methodist Church.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The New Room Bristol (2017). "New Room Archives". The New Room Bristol, John Wesley’s Chapel. Retrieved 20 July 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tooley, Mark (2014). "John Wesley and Religious Freedom". First Things. Retrieved 13 December 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Karen B. Westerfield (July 1996). "John Wesley's Prayer Book Revision: The Text in Context" (PDF). Methodist History. General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church. 34 (4): 230–247.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- UMC of Indiana (2019). "The Christmas Gift: A New Church". Manchester City Council. The United Methodist Church of Indiana. Retrieved 11 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Robert J. (2012). "Marking John Wesley's birthday in his words". UM News. Retrieved 13 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yoon, Young Hwi (2012). "The Spread of Antislavery Sentiment through Proslavery Tracts in the Transatlantic Evangelical Community, 1740s–1770s". Church History. 81 (2): 355. doi:10.1017/S0009640712000637.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading[edit]

- Abraham, William J. (2005). Wesley for Armchair Theologians. Louisville: Presbyterian Publishing Corporation.

- Benge, Janet; Benge, Geoff (2011). John Wesley: The World His Parish. Seattle, WA: YWAM Publishing.

- Blackman, Francis 'Woodie' (2003). John Wesley 300: Pioneers, Preachers and Practitioners. Babados: Panagraphix Inc.

- Borgen, Ole E. (1985). John Wesley on the Sacraments: a Theological Study. Grand Rapids, MI.: Francis Asbury Press.

- Collins, Kenneth J. (1989). Wesley on Salvation: A Study in the Standard Sermons. Grand Rapids, MI.: Francis Asbury Press.

- Collins, Kenneth J. (1997). The Scripture Way of Salvation: The Heart of John Wesley's Theology. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

- Collins, Kenneth J. (2007). The Theology of John Wesley: Holy Love and the Shape of Grace. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

- Green, Richard (1905). John Wesley, evangelist. London: Religious tract Society.

- Hammond, Geordan (2014). John Wesley in America: Restoring Primitive Christianity'. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Harper, Steve (2003). The Way to Heaven: The Gospel According to John Wesley. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Jennings, Daniel R. (2005). The Supernatural Occurrences of John Wesley. Sean Multimedia.

- Lindström, Harald (1946). Wesley and Sanctification: A Study in the Doctrine of Salvation. London: Epworth Press.

- Maddox, Randy L.; Vickers, Jason E. (2010). The Cambridge Companion to John Wesley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oden, Thomas (1994). John Wesley's Scriptural Christianity: A Plain Exposition of His Teaching on Christian Doctrine. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Synan, Vinson (1997). The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co.

- Taylor, G. W. (1905). "John Wesley and the Anglo-Catholic Revival". Making of the Modern World, Part III (1890–1945). London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Tedford, John (1885). The life of John Wesley. New York: Eaton & Mains.

- Vickers, Jason E. (2009). Wesley: A Guide for the Perplexed. London: T & T Clark.

Historiography[edit]

- Collins, Kenneth J. (2016). A Wesley Bibliography. Wilmore, Kentucky: First Fruits Press.

External links[edit]

- "Wesley Center Online". Wesley Center for Applied Theology. Northwest Nazarene University. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- John Wesley at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

- Works by John Wesley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Wesley at Internet Archive

- Works by John Wesley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Selected text from the Journal of John Wesley on A Vision of Britain through Time, with links to the places named.

- John Wesley papers, 1735–1791 at Pitts Theology Library, Candler School of Theology

- John Wesley historical marker in Savannah, Georgia

- A Man Named Wesley Passed This Way historical marker at St. Simons Island, Georgia

- Reverends John & Charles Wesley historical marker

- The World Is My Parish historical marker

- Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University: John Wesley family papers, 1734-1864 (MSS 100)

- 1703 births

- 1791 deaths

- 18th-century apocalypticists

- 18th-century English Anglican priests

- 18th-century English Christian theologians

- Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

- Anglican saints

- Arminian ministers

- Arminian theologians

- Arminian writers

- British expatriates in the United States

- Burials at Wesley's Chapel

- Christian radicals

- Christian revivalists

- Christianity in London

- Christianity in Oxford

- Church of England hymnwriters

- English abolitionists

- English Anglican missionaries

- English Anglican theologians

- English diarists

- English letter writers

- English Methodist hymnwriters

- Hymnal editors

- English pamphleteers

- English sermon writers

- Evangelical Anglican clergy

- Evangelical Anglican theologians

- Fellows of Lincoln College, Oxford

- Founders of religions

- German–English translators

- Methodist theologians

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- People educated at Charterhouse School

- People from Epworth, Lincolnshire

- People of Georgia (British colony)

- Presidents of the Methodist Conference

- Protestant missionaries in England

- Protestant missionaries in Scotland

- Protestant missionaries in the United States

- Translators of the Bible into English

- Wesley family