History of opium in China

The history of opium in China began with the use of opium for medicinal purposes during the 7th century. In the 17th century the practice of mixing opium with tobacco for smoking spread from Southeast Asia, creating a far greater demand.[1]

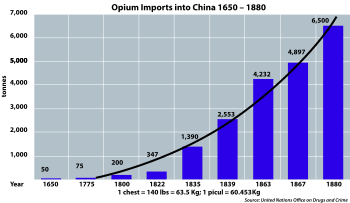

Imports of opium into China stood at 200 chests annually in 1729,[1] when the first anti-opium edict was promulgated.[2][3] By the time Chinese authorities reissued the prohibition in starker terms in 1799,[4] the figure had leaped; 4,500 chests were imported in the year 1800.[1] The decade of the 1830s witnessed a rapid rise in opium trade,[5] and by 1838, just before the First Opium War, it had climbed to 40,000 chests.[5] The rise continued on after the Treaty of Nanking (1842) that concluded the war. By 1858 annual imports had risen to 70,000 chests (4,480 long tons (4,550 t)), approximately equivalent to global production of opium for the decade surrounding the year 2000.[6]

By the late 19th century Chinese domestic opium production challenged and then surpassed imports. The 20th century opened with effective campaigns to suppress domestic farming, and in 1907 the British government signed a treaty to eliminate imports. The fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, however, led to a resurgence in domestic production. The Nationalist Government, provincial governments, the revolutionary bases of the Communist Party of China, and the British colonial government of Hong Kong all depended on opium taxes as major sources of revenue, as did the Japanese occupation governments during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).[citation needed] After 1949, both the respective governments of the People's Republic of China on the mainland and of the Republic of China on Taiwan claimed to have successfully suppressed the widespread growth and use of opium.[7][8] In fact, opium products were still in production in Xinjiang and Northeast China.[9][10]

Early history[edit]

Historical accounts suggest that opium first arrived in China during the Tang dynasty (618–907) as part of the merchandise of Arab traders.[11] Later on, Song Dynasty (960–1279) poet and pharmacologist Su Dongpo recorded the use of opium as a medicinal herb: "Daoists often persuade you to drink the jisu water, but even a child can prepare the yingsu[A] soup."[12]

Initially used by medical practitioners to control bodily fluid and preserve qi or vital force, during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the drug also functioned as an aphrodisiac or chunyao (春药) as Xu Boling records in his mid-fifteenth century Yingjing Juan:

It is mainly used to treat masculinity, strengthen sperm, and regain vigour. It enhances the art of alchemists, sex and court ladies. Frequent use helps to cure the chronic diarrhea that causes the loss of energy ... Its price equals that of gold.[12]

Ming rulers obtained opium via the tributary system, when it was known as wuxiang (烏香) or "black spice". The Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty record gifts to successive Ming emperors of up to 100 kilograms (220 lb) of wuxiang amongst tribute from the Kingdom of Siam, which also included frankincense, costus root, pepper, ivory, rhino horn and peacock feathers.

First listed as a taxable commodity in 1589[citation needed], opium remained legal until the end of Ming dynasty, 1637.[citation needed]

Growth of the opium trade[edit]

In the 16th century the Portuguese became aware of the lucrative medicinal and recreational trade of opium into China, and from their factories across Asia chose to supply the Cantons, to satisfy both the medicinal and the recreational use of the drug. By 1729 the Yongzheng Emperor had criminalised the new recreational smoking of opium in his empire. Following the 1764 Battle of Buxar, the British East India Company (EIC) gained control of tax collection, along with the former Mughal emperors monopoly on the opium market, in the province of Bengal, this monopoly was formally incorporated into the company's activities via the East India Company Act, 1793.[13] The EIC was £28 million in debt as a result of the Indian war and the insatiable demand for Chinese tea in the UK market, which had to be paid for in silver.[14][15] To redress the imbalance, the EIC began auctions of opium, offered in lieu of taxes, in Calcutta and saw its profits soar from the opium trade. Considering that importation of opium into China had been virtually banned by Chinese law, the East India Company established an elaborate trading scheme partially relying on legal markets and partially leveraging illicit ones. British merchants carrying no opium would buy tea in Canton (now known as Guangzhou) on credit, and balance their debts by selling opium at auction in Calcutta. From there, the opium would reach the Chinese coast hidden aboard British ships; it was then smuggled into China by native merchants. According to 19th Century sinologist Edward Parker, there were four types of opium smuggled into China from India: kung pan t'ou (公班土, gongban tu or "Patna"); Pak t'ou (白土, bai tu or "Malwa"); Persian, Kem fa t'ou (金花土, jinhua tu) and the "smaller kong pan", which was of a "dearer sort", i.e. more expensive.[16] A description of the cargo aboard Hercules at Lintin in July 1833 distinguished between "new" and "old" Patna, "new" and "old" Benares, and Malwa; the accounting also specifies the number of chests of each type, and the price per chest. The "chests"[B] contained small balls of opium that had originated in the Indian provinces of Bengal and Madras.

In 1797 the EIC further tightened its grip on the opium trade by enforcing direct trade between opium farmers and the British, and ending the role of Bengali purchasing agents. British exports of opium to China grew from an estimated 15 long tons (15,000 kg) in 1730 to 75 long tons (76,000 kg) in 1773 shipped in over two thousand chests.[17] The Qing dynasty Jiaqing Emperor issued an imperial decree banning imports of the drug in 1799. By 1804 the trade deficit with China had turned into a surplus, leading to seven million silver dollars going to India between 1806 and 1809. Meanwhile, Americans entered the opium trade with less expensive but inferior Turkish opium and by 1810 had around 10% of the trade in Canton.[15]

In the same year the Emperor issued a further imperial edict:

Opium has a harm. Opium is a poison, undermining our good customs and morality. Its use is prohibited by law. Now the commoner, Yang, dares to bring it into the Forbidden City. Indeed, he flouts the law! However, recently the purchasers, eaters, and consumers of opium have become numerous. Deceitful merchants buy and sell it to gain profit. The customs house at the Ch'ung-wen Gate was originally set up to supervise the collection of imports (it had no responsibility with regard to opium smuggling). If we confine our search for opium to the seaports, we fear the search will not be sufficiently thorough. We should also order the general commandant of the police and police- censors at the five gates to prohibit opium and to search for it at all gates. If they capture any violators, they should immediately punish them and should destroy the opium at once. As to Kwangtung [Guangdong] and Fukien [Fujian], the provinces from which opium comes, we order their viceroys, governors, and superintendents of the maritime customs to conduct a thorough search for opium, and cut off its supply. They should in no ways consider this order a dead letter and allow opium to be smuggled out![18]

The decree had little effect. The Qing government, far away in Beijing in the north of China, was unable to halt opium smuggling in the southern provinces. A porous Chinese border and rampant local demand facilitated the trade and by the 1820s China was importing 900 long tons (910 t) of Bengali opium annually.[19]

The opium trafficked into China was processed by the EIC at its two factories in Patna and Benares. In the 1820s, opium from Malwa in the non-British controlled part of India became available, and as prices fell due to competition, production was stepped up.[20]

In addition to the drain of silver, by 1838 the number of Chinese opium addicts had grown to between four and twelve million[21] and the Daoguang Emperor demanded action. Officials at the court who advocated legalizing and taxing the trade were defeated by those who advocated suppressing it. The Emperor sent the leader of the hard line faction, Special Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu, to Canton, where he quickly arrested Chinese opium dealers and summarily demanded that foreign firms turn over their stocks with no compensation. When they refused, Lin stopped trade altogether and placed the foreign residents under virtual siege in their factories, eventually forcing the merchants to surrender their opium. Lin destroyed the confiscated opium, a total of some 1,000 long tons (1,016 t), a process which took 23 days.

First Opium War[edit]

In compensation for the opium destroyed by Commissioner Lin British traders demanded compensation from their home government. However, British authorities believed that the Chinese were responsible for payment and sent expeditionary forces from India, which ravaged the Chinese coast in a series of battles and dictated the terms of settlement. The 1842 Treaty of Nanking not only opened the way for further opium trade, but ceded the territory of Hong Kong, unilaterally fixed Chinese tariffs at a low rate, gave Britain most favored nation status and permitted them diplomatic representation. Three million dollars in compensation for debts that the Hong merchants in Canton owed British merchants for the destroyed opium was also to be paid under Article V.

Taiping Rebellion[edit]

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom opposed the usage of opium.[22] Fear that the Taiping forces would destroy opium stocks owned by foreign trades was one reason that Western powers joined the conflict on the side of the Qing dynasty.

Second Opium War[edit]

Despite the new ports available for trade under the Treaty of Nanking, by 1854 Britain's imports from China had reached nine times their exports to the country. At the same time British imperial finances came under further pressure from the expense of administering the burgeoning colonies of Hong Kong and Singapore in addition to India. Only the latter's opium could balance the deficit. [23] Along with various complaints about the treatment of British merchants in Chinese ports and the Qing government's refusal to accept further foreign ambassadors, the relatively minor "Arrow Incident" provided the pretext the British needed to once more resort to military force to ensure the opium kept flowing. The Arrow was a merchant lorcha with an expired British registration that the Qing authorities seized for alleged salt smuggling. British authorities complained to the Governor-general of Liangguang, Ye Mingchen, that the seizure breached Article IX of the 1843 Treaty of the Bogue with regard to extraterritoriality. Matters quickly escalated and led to the Second Opium War, sometimes referred to as the "Arrow War" or the "Second Anglo-Chinese War", which broke out in 1856. A number of clashes followed until the war ended with the signature of the Treaty of Tientsin in 1860.[24] Although the new treaty did not expressly legalise opium, it opened a further five ports to trade and for the first time allowed foreign traders access to the vast hinterland of China beyond the coast.

Aftermath of the Opium Wars[edit]

The treaties with the British soon led to similar arrangements with the United States and France. These later became known as the Unequal Treaties, while the Opium Wars, according to Chinese historians, represented the start of China's "Century of humiliation".

The opium trade faced intense enmity from the later British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone.[25] As a member of Parliament, Gladstone called it "most infamous and atrocious" referring to the opium trade between China and British India in particular.[26] Gladstone was fiercely against both of the Opium Wars and ardently opposed to the British trade in opium to China.[27] He lambasted it as "Palmerston's Opium War" and said that he felt "in dread of the judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China" in May 1840.[28] Gladstone criticized it as "a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace,".[29] His hostility to opium stemmed from the effects of opium brought upon his sister Helen.[30] Due to the First Opium war brought on by Palmerston, there was initial reluctance to join the government of Peel on part of Gladstone before 1841.[31]

Domestication and suppression in the last decades of the Qing dynasty[edit]

We English, by the policy we have pursued, are morally responsible for every acre of land in China which is withdrawn from the cultivation of grain and devoted to that of the poppy; so that the fact of the growth of the drug in China ought only to increase our sense of responsibility.[32]

Once the turmoil caused by the mid-century Taiping Rebellion died down, the economy came to depend on opium to play several roles. Merchants found the substance useful as a substitute for cash, as it was readily accepted in the interior provinces such as Sichuan and Yunnan while the drug weighed less than the equivalent amount of copper. Since poppies could be grown in almost any soil or weather, cultivation quickly spread. Local officials could then meet their tax quotas by relying on poppy growers even in areas where other crops had not recovered. Although the government continued to require suppression, local officials often merely went through the motions both because of bribery and because they wanted to avoid antagonizing local farmers who depended on this lucrative crop. One official complained that when people heard a government inspector was coming, they would merely pull up a few poppy stalks to spread by the side of the road to give the appearance of complying. A provincial governor observed that opium, once regarded as a poison, was now treated in the same way as tea or rice. By the 1880s, even governors who had initially suppressed opium smoking and poppy production now depended on opium taxes.

The historian Jonathan Spence notes that the harm opium caused has long been clear, but that in a stagnating economy, opium supplied fluid capital and created new sources of taxes. Smugglers, poor farmers, coolies, retail merchants and officials all depended on opium for their livelihood. In the last decade of the dynasty, however, a focused moral outrage overcame these vested interests.[33]

When the Qing government launched new opium suppression campaigns after 1901, the opposition no longer came from the British, whose sales had suffered greatly from domestic competition in any case, but from Chinese farmers who would be wiped out by the loss of their most profitable crop-derivative. Further opposition to the government moves came from wholesalers and retailers as well as from the millions of opium users, many of whom came from influential families.[34] The government persevered, creating further dissent amongst the people, and at the same time promoted cooperation with international anti-narcotic agencies. Nevertheless, despite the imposition of new blanket import duties under the 1902 Mackay Treaty, Indian opium remained exempt and taxable at 110 taels per chest with the treaty stating "there was no intention of interfering with China's right to tax native opium".[35]

The International Opium Commission observed that opium smoking was a fashionable, even refined pastime, especially among the young, yet many in society condemned the habit. In 1907 Great Britain signed a treaty agreeing to gradually eliminate opium exports to China over the next decade while China agreed to eliminate domestic production over that period. Estimates of domestic production fell from 35,000 metric tons (34,000 long tons) in 1906 to 4,000 metric tons (3,900 long tons) in 1911. By the same year, the combination of foreign and domestic efforts proved largely successful, but the fall of the Qing government in 1911 effectively meant the end of the campaign. Local and provincial governments quickly turned back to opium as a source of revenue, and foreign governments no longer felt obliged to continue their efforts to eliminate the trade.[36]

In the northern provinces of Ningxia and Suiyuan in China, Chinese Muslim General Ma Fuxiang both prohibited and engaged in the opium trade. It was hoped that Ma Fuxiang would have improved the situation, since Chinese Muslims were well known for opposition to smoking opium.[37] Ma Fuxiang officially prohibited opium and made it illegal in Ningxia, but the Guominjun reversed his policy; by 1933, people from every level of society were abusing the drug, and Ningxia was left in destitution.[38] In 1923, an officer of the Bank of China from Baotou found out that Ma Fuxiang was assisting the drug trade in opium which helped finance his military expenses. He earned $2 million from taxing those sales in 1923. General Ma had been using the bank, a branch of the Government of China's exchequer, to arrange for silver currency to be transported to Baotou to use it to sponsor the trade.[39]

Since 1940, to solve financial crisis, CCP government in Shaan-Gan-Ning had begun opium plantation and dealing, selling them to Japanese-occupied and Kuomintang provinces. The KMT government tried to send in an opium-prohibition inspection team but was turned down by the communists.

During Kuomintang rule over the Republic of China opium trafficking was used for funds by Chiang Kai-shek.[40]

Under Mao[edit]

The Mao Zedong government is generally credited with eradicating both consumption and production of opium during the 1950s using unrestrained repression and social reform.[9][10] Ten million addicts were forced into compulsory treatment, dealers were executed, and opium-producing regions were planted with new crops. Remaining opium production shifted south of the Chinese border into the Golden Triangle region.[41] The remnant opium trade primarily served Southeast Asia, but spread to American soldiers during the Vietnam War, with 20 percent of soldiers regarding themselves as addicted during the peak of the epidemic in 1971. In 2003, China was estimated to have four million regular drug users and one million registered drug addicts.[42]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yingsu (罂粟) refers to the poppy, Papaver somniferum, and was used an alternative name for opium.

- ^ A chest of opium contained approximately 100 "catties" or 1 "picul", with each catty weighing 1.33 lb (600 g), giving a total of ~140 pounds (64 kg)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Ebrey 2010, p. 236.

- ^ Greenberg 1969, pp. 108, 110 citing Edkins, Owen, Morse, International Relations.

- ^ Keswick & Weatherall 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Greenberg 1969, p. 29.

- ^ a b Greenberg 1969, p. 113.

- ^ "Global opium production", The Economist, 24 June 2010, retrieved 29 October 2012

- ^ Baumler 2001, p. 1-2.

- ^

Baumler, Alan, ed. (2001). Modern China and Opium: A Reader. University of Michigan Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780472067688. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

Although many of the specific techniques they used were similar to those of the Nationalists, the Communist anti-opium campaigns were carried out in the context of the successful effort to use mass campaigns to bring all aspects of local life under control, and thus the Communists were considerably more successful than were the Nationalists. Opium and drug use would not be a problem again in China until the post-Mao era.

- ^ a b United States Congress Senate Committee on the Judiciary. Communist china and illicit narcotic traffic. 1955年: United States Government Printing Office. OCLC 6466332.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ a b Nei zheng bu (1956). Chinese communists' world-wide narcotic war. Taipei,Taiwan: Ministry of Interior, Republic of China. OCLC 55592114.

- ^ Li & Fang 2013, p. 190.

- ^ a b Zheng 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Brewster 1832, p. 275.

- ^ Lovell 2012, 176 of 11144.

- ^ a b Layton 1997, p. 28.

- ^ Parker & Wei 1888, p. 7.

- ^ Salucci, Lapo (2007). Depths of Debt: Debt, Trade and Choices Archived 28 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. University of Colorado.

- ^ Fu, Lo-shu (1966). A Documentary Chronicle of Sino-Western relations, Volume 1. p. 380.

- ^ Bertelsen, Cynthia (19 October 2008). "A novel of the British opium trade in China." Roanoke Times & World News.

- ^ Keswick & Weatherall 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 34.

- ^ Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795-1989 - Bruce A. Elleman - Google Books

- ^ Brook & Wakabayashi 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Ebrey & Walthall 2013, p. 378–82.

- ^ Kathleen L. Lodwick (5 February 2015). Crusaders Against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874–1917. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-0-8131-4968-4.

- ^ Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy (2009). Opium: Uncovering the Politics of the Poppy. Harvard University Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-674-05134-8.

- ^ Dr Roland Quinault; Dr Ruth Clayton Windscheffel; Mr Roger Swift (28 July 2013). William Gladstone: New Studies and Perspectives. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-1-4094-8327-4.

- ^ Ms Louise Foxcroft (28 June 2013). The Making of Addiction: The 'Use and Abuse' of Opium in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-1-4094-7984-0.

- ^ Peter Ward Fay (9 November 2000). The Opium War, 1840–1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the War by which They Forced Her Gates Ajar. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-0-8078-6136-3.

- ^ Anne Isba (24 August 2006). Gladstone and Women. A&C Black. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-1-85285-471-3.

- ^ David William Bebbington (1993). William Ewart Gladstone: Faith and Politics in Victorian Britain. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-0-8028-0152-4.

- ^ Spencer Hill, J. (1884). The Indo-Chinese opium trade considered in relation to its history, morality, and expediency, and its influence on Christian missions. London: Henry Frowde. Prefatory note by Lord Justice Fry.

- ^ Spence, Jonathan (1975), "Opium Smoking in Ch'ing China", in Wakeman Frederic (ed.), Conflict and Control in Late Imperial China, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 143–173 reprinted in Spence, Jonathan D. (1992). Chinese Roundabout: Essays in History and Culture. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393033554.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) pp. 250–255

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. (2013). The Search for Modern China. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393934519.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) pp. 244–245.

- ^ Lowes 1966, p. 73.

- ^ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Bulletin on Narcotics: A Century of International Drug Control (Vienna, Austria: 2010) pp. 57–58

- ^ Ann Heylen (2004). Chronique du Toumet-Ortos: Looking through the Lens of Joseph Van Oost, Missionary in Inner Mongolia (1915–1921). Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. p. 312. ISBN 90-5867-418-5. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Association for Asian Studies. Southeast Conference (1979). Annals, Volumes 1–5. The Conference. p. 51. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Edward R. Slack (2001). Opium, State, and Society: China's Narco-Economy and the Guomindang, 1924–1937. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 240. ISBN 0-8248-2361-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ http://criticalasianstudies.org/assets/files/bcas/v08n03.pdf Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. 19

- ^ Alfred W. McCoy. "Opium History, 1858 to 1940". Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ Michael Mackey (29 April 2004). "Banned in China for sex, drugs, disaffection". Retrieved 8 June 2007.

Bibliography[edit]

- Baumler, Alan (2001). Modern China and Opium: A Reader. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472067688.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brewster, David (1832). The Edinburgh encyclopaedia. 11. J. and E. Parker.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010). "9. Manchus and Imperialism: The Qing Dynasty 1644–1900". The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (second ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19620-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne (2013). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781285528670.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brook, Timothy; Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi (2000). Opium Regimes: China, Britain, and Japan, 1839–1952. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520222366.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keswick, Maggie; Weatherall, Clara (2008). The Thistle and the Jade: A Celebration of 175 Years of Jardine Matheson. Frances Lincoln. ISBN 9780711228306.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greenberg, Michael (1969). British Trade and the Opening of China, 1800–42. Cambridge Studies in Economic History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanes, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2002). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. ISBN 9781402201493.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Layton, Thomas N. (1997). The Voyage of the 'Frolic': New England Merchants and the Opium Trade. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804729093.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lowes, Peter D. (1966). The Genesis of International Narcotics Control. Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-04030-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lovell, Julia (2012). The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China. Picador. ISBN 978-1-4472-0410-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Kindle version)

- Li, Xiaobing; Fang, Qiang (2013). Modern Chinese Legal Reform: New Perspectives. Asia in the new millennium. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813141206.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parker, Edward Harper; Wei, Yuan (1888). 圣武记 [Chinese Account of the Opium War]. The Pagoda Library. Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zheng, Yangwen (2005). The Social Life of Opium in China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521846080.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading[edit]

- Dikötter, Frank; Lars, Peter Laamann; Zhou, Xun (2004). Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1850657255.

- McMahon, Keith (2002). The Fall of the God of Money : Opium Smoking in Nineteenth-Century China. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0742518027.

- Zhou, Yongming (1999). Anti-Drug Crusades in Twentieth Century China: Nationalism, History, and State Building. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 9780847695980.