David

| David | |

|---|---|

Statue of King David (1609–1612) by Nicolas Cordier in the Borghese Chapel of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, Italy | |

| King of Israel | |

| Reign | c. 1010–970 BCE |

| Predecessor | Ish-bosheth |

| Successor | Solomon |

| Consort | |

| Issue | |

| House | House of David |

| Father | Jesse |

| Mother | Nitzevet (Talmud) |

| Religion | Judaism |

David (Hebrew: דָּוִד)[a] is described in the Hebrew Bible as the third king of the United Monarchy of Israel and Judah,[b] becoming king after Ish-bosheth. In the Books of Samuel, David is a young shepherd who gains fame first as a musician and later by killing the enemy champion Goliath. He becomes a favorite of King Saul and a close friend of Saul's son Jonathan. Worried that David is trying to take his throne, Saul turns on David. After Saul and Jonathan are killed in battle, David is anointed as King. David conquers Jerusalem, taking the Ark of the Covenant into the city, and establishing the kingdom founded by Saul. As king, David commits adultery with Bathsheba, leading him to arrange the death of her husband Uriah the Hittite. Because of this sin, David's son Absalom tries to overthrow him. David flees Jerusalem during Absalom's rebellion, but after Absalom's death he returns to the city to rule Israel. Because David shed much blood,[2] God denies David the opportunity to build the temple. Before his peaceful death, he chooses his son Solomon as successor. He is honored in the prophetic literature as an ideal king and the forefather of a future Messiah, and many psalms are ascribed to him.

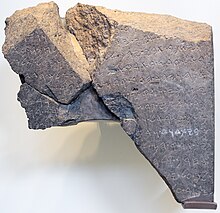

Historians of the Ancient Near East agree that David probably existed around 1000 BCE, but that there is little that can be said about him as a historical figure. It was initially thought that there was no evidence outside of the Bible concerning David, but the Tel Dan Stele, an inscribed stone erected by a king of Damascus in the late 9th/early 8th centuries BCE to commemorate his victory over two enemy kings, contains the phrase in Hebrew: ביתדוד, bytdwd, which most scholars translate as "House of David".

David is richly represented in post-biblical Jewish written and oral tradition, and is discussed in the New Testament. Early Christians interpreted the life of Jesus in light of the references to the Messiah and to David; Jesus is described as being descended from David in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. David is discussed in the Quran as a major prophet and figures in Islamic oral and written tradition as well. The biblical character of David has inspired many interpretations in art and literature over centuries.

Biblical account[edit]

Family[edit]

The First Book of Samuel and the First Book of Chronicles both identify David as the son of Jesse, the Bethlehemite, the youngest of eight sons.[3] He also had at least two sisters, Zeruiah, whose sons all went on to serve in David's army, and Abigail, whose son Amasa went on to serve in Absalom's army, Absalom being one of David's younger sons.[4] While the Bible does not name his mother, the Talmud identifies her as Nitzevet, a daughter of a man named Adael, and the Book of Ruth claims him as the great-grandson of Ruth, the Moabite, by Boaz.[5]

David is described as cementing his relations with various political and national groups through marriage.[6] King Saul initially offered David his oldest daughter, Merab. David did not refuse the offer, but humbled himself in front of Saul to be considered among the King's family.[7] Saul reneged and instead gave Merab in marriage to Adriel the Meholathite.[8] Having been told that his younger daughter Michal was in love with David, Saul gave her in marriage to David upon David's payment in Philistine foreskins[9] (ancient Jewish historian Josephus lists the dowry as 600 Philistine heads).[10] Saul became jealous of David and tried to have him killed. David escaped. Then Saul sent Michal to Galim to marry Palti, son of Laish.[11] David then took wives in Hebron, according to 2 Samuel 3; they were Ahinoam the Yizre'elite; Abigail, the wife of Nabal the Carmelite; Maacah, the daughter of Talmay, king of Geshur; Haggith; Abital; and Eglah. Later, David wanted Michal back and Abner, Ish-bosheth's army commander, delivered her to David, causing her husband (Palti) great grief.[12]

The Book of Chronicles lists his sons with his various wives and concubines. In Hebron, David had six sons: Amnon, by Ahinoam; Daniel, by Abigail; Absalom, by Maachah; Adonijah, by Haggith; Shephatiah, by Abital; and Ithream, by Eglah.[13] By Bathsheba, his sons were Shammua, Shobab, Nathan, and Solomon. David's sons born in Jerusalem of his other wives included Ibhar, Elishua, Eliphelet, Nogah, Nepheg, Japhia, Elishama and Eliada.[14] Jerimoth, who is not mentioned in any of the genealogies, is mentioned as another of his sons in 2 Chronicles 11:18. His daughter Tamar, by Maachah, is raped by her half-brother Amnon. David fails to bring Amnon to justice for his violation of Tamar, because he is his firstborn and he loves him, and so, Absalom (her full brother) murders Amnon to avenge Tamar.[15]

Narrative[edit]

God is angered when Saul, Israel's king, unlawfully offers a sacrifice[16] and later disobeys a divine command both to kill all of the Amalekites and to destroy their confiscated property.[17] Consequently, God sends the prophet Samuel to anoint a shepherd, David, the youngest son of Jesse of Bethlehem, to be king instead.[18]

After God sends an evil spirit to torment Saul, his servants recommend that he send for a man skilled in playing the lyre. A servant proposes David, whom the servant describes as "skillful in playing, a man of valor, a warrior, prudent in speech, and a man of good presence; and the Lord is with him." David enters Saul's service as one of the royal armour-bearers and plays the lyre to soothe the king.[19]

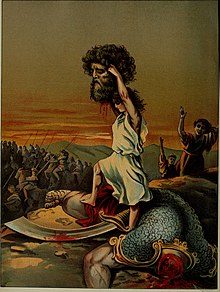

War comes between Israel and the Philistines, and the giant Goliath challenges the Israelites to send out a champion to face him in single combat.[20] David, sent by his father to bring provisions to his brothers serving in Saul's army, declares that he can defeat Goliath.[21] Refusing the king's offer of the royal armour,[22] he kills Goliath with his sling.[23] Saul inquires the name of the young hero's father.[24]

Saul sets David over his army. All Israel loves David, but his popularity causes Saul to fear him ("What else can he wish but the kingdom?").[25] Saul plots his death, but Saul's son Jonathan, one of those who loves David, warns him of his father's schemes and David flees. He goes first to Nob, where he is fed by the priest Ahimelech and given Goliath's sword, and then to Gath, the Philistine city of Goliath, intending to seek refuge with King Achish there. Achish's servants or officials question his loyalty, and David sees that he is in danger there.[26] He goes next to the cave of Adullam, where his family join him.[27] From there he goes to seek refuge with the king of Moab, but the prophet Gad advises him to leave and he goes to the Forest of Hereth,[28] and then to Keilah, where he is involved in a further battle with the Philistines. Saul plans to besiege Keilah so that he can capture David, so David leaves the city in order to protect its inhabitants.[29] From there he takes refuge in the mountainous Wilderness of Ziph.[30]

Jonathan meets with David again and confirms his loyalty to David as the future king. After the people of Ziph notify Saul that David is taking refuge in their territory, Saul seeks confirmation and plans to capture David in the Wilderness of Maon, but his attention is diverted by a renewed Philistine invasion and David is able to secure some respite at Ein Gedi.[31] Returning from battle with the Philistines, Saul heads to Ein Gedi in pursuit of David and enters the cave where, as it happens, David and his supporters are hiding, "to attend to his needs". David realises he has an opportunity to kill Saul, but this is not his intention: he secretly cuts off a corner of Saul's robe, and when Saul has left the cave he comes out to pay homage to Saul as the king and to demonstrate, using the piece of robe, that he holds no malice towards Saul. The two are thus reconciled and Saul recognises David as his successor.[32]

A similar passage occurs in 1 Samuel 26, when David is able to infiltrate Saul's camp on the hill of Hachilah and remove his spear and a jug of water from his side while he and his guards lie asleep. In this account, David is advised by Abishai that this is his opportunity to kill Saul, but David declines, saying he will not "stretch out [his] hand against the Lord's anointed".[33] Saul confesses that he has been wrong to pursue David and blesses him.[34]

In 1 Samuel 27:1–4, Saul ceases to pursue David because David took refuge a second[35] time with Achish, the Philistine king of Gath. Achish permits David to reside in Ziklag, close to the border between Gath and Judea, from where he leads raids against the Geshurites, the Girzites and the Amalekites, but leads Achish to believe he is attacking the Israelites in Judah, the Jerahmeelites and the Kenites. Achish believes that David had become a loyal vassal, but he never wins the trust of the princes or lords of Gath, and at their request Achish instructs David to remain behind to guard the camp when the Philistines march against Saul.[36] David returns to Ziklag.[37] Jonathan and Saul are killed in battle,[38] and David is anointed king over Judah.[39] In the north, Saul's son Ish-Bosheth is anointed king of Israel, and war ensues until Ish-Bosheth is murdered.[40]

With the death of Saul's son, the elders of Israel come to Hebron and David is anointed king over all of Israel.[41] He conquers Jerusalem, previously a Jebusite stronghold, and makes it his capital.[42] He brings the Ark of the Covenant to the city,[43] intending to build a temple for God, but the prophet Nathan forbids it, prophesying that the temple would be built by one of David's sons.[44] Nathan also prophesies that God has made a covenant with the house of David stating, "your throne shall be established forever".[45] David wins additional victories over the Philistines, Moabites, Edomites, Amalekites, Ammonites and king Hadadezer of Aram-Zobah, after which they become tributaries.[46]

During a siege of the Ammonite capital of Rabbah, David remains in Jerusalem. He spies a woman, Bathsheba, bathing and summons her; she becomes pregnant.[47][48][49] The text in the Bible does not explicitly state whether Bathsheba consented to sex.[50][51][52][53] David calls her husband, Uriah the Hittite, back from the battle to rest, hoping that he will go home to his wife and the child will be presumed to be his. Uriah does not visit his wife, however, so David conspires to have him killed in the heat of battle. David then marries the widowed Bathsheba.[54] In response, Nathan prophesies the punishment that will fall upon him, stating "the sword shall never depart from your house."[55] When David acknowledges that he has sinned,[56] Nathan advises him that his sin is forgiven and he will not die,[57] but the child will.[58] In fulfillment of Nathan's words, David's son Absalom, fueled by vengeance and lust for power, rebels.[59] Absalom's forces are routed at the battle of the Wood of Ephraim, and he is caught by his long hair in the branches of a tree where, contrary to David's order, he is killed by Joab, the commander of David's army.[60] David laments the death of his favourite son: "O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!"[61] until Joab persuades him to recover from "the extravagance of his grief"[62] and to fulfill his duty to his people.[63] David returns to Gilgal and is escorted across the River Jordan and back to Jerusalem by the tribes of Judah and Benjamin.[64]

When David is old and bedridden, Adonijah, his eldest surviving son and natural heir, declares himself king.[65] Bathsheba and Nathan go to David and obtain his agreement to crown Bathsheba's son Solomon as king, according to David's earlier promise, and the revolt of Adonijah is put down.[66] David dies at the age of 70 after reigning for 40 years,[67] and on his deathbed counsels Solomon to walk in the ways of God and to take revenge on his enemies.[68]

Psalms[edit]

The Book of Samuel calls David a skillful harp (lyre) player[70] and "the sweet psalmist of Israel."[71] Yet, while almost half of the Psalms are headed "A Psalm of David" (also translated as "to David" or "for David") and tradition identifies several with specific events in David's life (e.g., Psalms 3, 7, 18, 34, 51, 52, 54, 56, 57, 59, 60, 63 and 142),[72] the headings are late additions and no psalm can be attributed to David with certainty.[73]

Psalm 34 is attributed to David on the occasion of his escape from Abimelech (or King Achish) by pretending to be insane.[74] According to the parallel narrative in 1 Samuel 21, instead of killing the man who had exacted so many casualties from him, Abimelech allows David to depart, exclaiming, "Am I so short of madmen that you have to bring this fellow here to carry on like this in front of me? Must this man come into my house?"[75]

History and archeology[edit]

The Tel Dan Stele, an inscribed stone erected by a king of Damascus in the late 9th/early 8th centuries BCE to commemorate his victory over two enemy kings, contains the phrase Hebrew: ביתדוד, bytdwd, which most scholars translate as "House of David".[76] Other scholars, such as Anson Rainey have challenged this reading,[77] but it is likely that this is a reference to a dynasty of the Kingdom of Judah which traced its ancestry to a founder named David.[76] The Mesha Stele from Moab, dating from approximately the same period, may also contain the name David in two places, although this is less certain than the mention in the Tel Dan inscription.[78]

Besides the two steles, bible scholar and egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen suggests that David's name also appears in a relief of Pharaoh Shoshenq (usually identified with Shishak in the Bible, 1 Kings 14:25-27).[79] The relief claims that Shoshenq raided places in Palestine in 925 BCE, and Kitchen interprets one place as "Heights of David", which was in Southern Judah and the Negev where the Bible says David took refuge from Saul. The relief is damaged and interpretation is uncertain.[79]

Apart from these, all that is known of David comes from the biblical literature. Some scholars have concluded that this was likely compiled from contemporary records of the 11th and 10th centuries BCE, but that there is no clear historical basis for determining the exact date of compilation.[80] Other scholars, such as A. Graeme Auld, Professor of Hebrew Bible at the University of Edinburgh, believe that the Books of Samuel were substantially composed during the time of King Josiah at the end of the 7th century BCE, extended during the Babylonian exile (6th century BCE), and substantially complete by about 550 BCE. Auld contends that further editing was done even after then—the silver quarter-shekel which Saul's servant offers to Samuel in 1 Samuel 9 "almost certainly fixes the date of the story in the Persian or Hellenistic period" because a quarter-shekel was known to exist in Hasmonean times.[81] The authors and editors of Samuel drew on many earlier sources, including, for their history of David, the "history of David's rise" (1 Samuel 16:14–2 Samuel 5:10), and the "succession narrative" (2 Samuel 9–20 and 1 Kings 1–2).[82] The Book of Chronicles, which tells the story from a different point of view, was probably composed in the period 350–300 BCE, and uses Samuel as its source.[83]

The authors and editors of Samuel and Chronicles did not aim to record history, but to promote David's reign as inevitable and desirable, and for this reason there is little about David that is concrete and undisputed.[84] The archaeological evidence indicates that in the 10th century BCE, the time of David, Judah was sparsely inhabited and Jerusalem was no more than a small village; over the following century it slowly evolved from a highland chiefdom to a kingdom, but always overshadowed by the older and more powerful kingdom of Israel to the north.[85] The biblical evidence likewise indicates that David's Judah was something less than a full-fledged monarchy: it often calls him negid, for example, meaning "prince" or "chief", rather than melek, meaning "king"; the biblical David sets up none of the complex bureaucracy that a kingdom needs (even his army is made up of volunteers), and his followers are largely related to him and from his small home-area around Hebron.[86]

Beyond this, the full range of possible interpretations is available. John Bright, in his History of Israel (1981), takes Samuel at face value. Donald B. Redford, however, sees all reconstructions from biblical sources for the United Monarchy period as examples of "academic wishful thinking".[87] Thomas L. Thompson rejects the historicity of the biblical narrative: "The history of Palestine and of its peoples is very different from the Bible's narratives, whatever political claims to the contrary may be. An independent history of Judea during the Iron I and Iron II periods has little room for historicizing readings of the stories of I-II Samuel and I Kings."[88] Amihai Mazar however, concludes that based on recent archeological findings, like those in City of David, Khirbet Qeiyafa, Tel Dan, Tel Rehov, Khirbat en-Nahas and others "the deconstruction of United Monarchy and the devaluation of Judah as a state in 9th century is unacceptable interpretation of available historic data". According to Mazar, based on archeological evidences, the United Monarchy can be described as a "state in development".[89]

Some studies of David have been written: Baruch Halpern has pictured David as a lifelong vassal of Achish, the Philistine king of Gath;[90] Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman have identified as the oldest and most reliable section of Samuel those chapters which describe David as the charismatic leader of a band of outlaws who captures Jerusalem and makes it his capital.[91] Steven McKenzie, Associate Professor of the Hebrew Bible at Rhodes College and author of King David: A Biography, argues that David came from a wealthy family, was "ambitious and ruthless" and a tyrant who murdered his opponents, including his own sons.[73]

Critical Bible scholarship holds that the biblical account of David's rise to power is a political apology—an answer to contemporary charges against him, of his involvement in murders and regicide.[92]

Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman reject the idea that David ruled over a united monarchy, suggesting instead that he ruled only as a chieftain over the southern kingdom of Judah, much smaller than the northern kingdom of Israel at that time.[93] They posit that Israel and Judah were still polytheistic or henotheistic in the time of David and Solomon, and that much later seventh-century redactors sought to portray a past golden age of a united, monotheistic monarchy in order to serve contemporary needs.[94] They note a lack of archeological evidence for David's military campaigns and a relative underdevelopment of Jerusalem, the capital of Judah, compared to a more developed and urbanized Samaria, capital of Israel.[95][96][97]

Jacob L. Wright, Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible at Emory University, has written that the most popular legends about David, including his killing of Goliath, his affair with Bathsheba, and his ruling of a United Kingdom of Israel rather than just Judah, are the creation of those who lived generations after him, in particular those living in the late Persian or Hellenistic periods.[98]

History of interpretation in the Abrahamic religions[edit]

Rabbinic Judaism[edit]

David is an important figure in Rabbinic Judaism, with many legends around him. According to one tradition, David was raised as the son of his father Jesse and spent his early years herding his father's sheep in the wilderness while his brothers were in school.[99]

David's adultery with Bathsheba is interpreted as an opportunity to demonstrate the power of repentance, and the Talmud states that it was not adultery at all, quoting a Jewish practice of divorce on the eve of battle. Furthermore, according to Talmudic sources, the death of Uriah was not to be considered murder, on the basis that Uriah had committed a capital offense by refusing to obey a direct command from the King.[100] However, in tractate Sanhedrin, David expressed remorse over his transgressions and sought forgiveness. God ultimately forgave David and Bathsheba but would not remove their sins from Scripture.[101]

In Jewish legend, David's sin with Bathsheba is the punishment for David's excessive self-consciousness who had besought God to lead him into temptation so that he might give proof of his constancy as Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (who successfully passed the test) whose names later were united with God's, while David eventually failed through the temptation of a woman.[102]

According to midrashim, Adam gave up 70 years of his life for the life of David.[103] Also, according to the Talmud Yerushalmi, David was born and died on the Jewish holiday of Shavuot (Feast of Weeks). His piety was said to be so great that his prayers could bring down things from Heaven.[citation needed]

Christianity[edit]

King David the Prophet | |

|---|---|

King David in Prayer, by Pieter de Grebber (c. 1640) | |

| Holy Monarch, Prophet, Reformer, Spiritual Poet and Musician, Vicegerent of God, Psalm-Receiver | |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholicism[104] Eastern Orthodoxy[105] Islam |

| Feast | December 29 – Roman Catholicism |

| Attributes | Psalms, Harp, Head of Goliath |

The concept of the Messiah is important in Christianity. Originally an earthly king ruling by divine appointment ("the anointed one", as the title Messiah had it), the "son of David" became in the last two pre-Christian centuries the apocalyptic and heavenly one who would deliver Israel and usher in a new kingdom. This was the background to the concept of Messiahship in early Christianity, which interpreted the career of Jesus "by means of the titles and functions assigned to David in the mysticism of the Zion cult, in which he served as priest-king and in which he was the mediator between God and man".[106] The early Church believed that "the life of David [foreshadowed] the life of Christ; Bethlehem is the birthplace of both; the shepherd life of David points out Christ, the Good Shepherd; the five stones chosen to slay Goliath are typical of the five wounds; the betrayal by his trusted counsellor, Achitophel, and the passage over the Cedron remind us of Christ's Sacred Passion. Many of the Davidic Psalms, as we learn from the New Testament, are clearly typical of the future Messiah."[107] In the Middle Ages, "Charlemagne thought of himself, and was viewed by his court scholars, as a 'new David'. [This was] not in itself a new idea, but [one whose] content and significance were greatly enlarged by him".[108] The linking of David to earthly kingship was reflected in European cathedral windows of the Late Middle Ages, through the device of the Tree of Jesse, its branches demonstrating how divine kingship descended from Jesse, through his son David, to Jesus.[citation needed]

Western Rite churches (Lutheran, Roman Catholic) celebrate his feast day on 29 December, Eastern-rite on 19 December.[109] The Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches celebrate the feast day of the "Holy Righteous Prophet and King David" on the Sunday of the Holy Forefathers (two Sundays before the Great Feast of the Nativity of the Lord), when he is commemorated together with other ancestors of Jesus. He is also commemorated on the Sunday after the Nativity, together with Joseph and James, the Brother of the Lord.[citation needed]

Middle Ages[edit]

In European Christian culture of the Middle Ages, David was made a member of the Nine Worthies, a group of heroes encapsulating all the ideal qualities of chivalry. His life was thus proposed as a valuable subject for study by those aspiring to chivalric status. This aspect of David in the Nine Worthies was popularised firstly through literature, and was thereafter adopted as a frequent subject for painters and sculptors.

David was considered as a model ruler and a symbol of divinely-ordained monarchy throughout medieval Western Europe and Eastern Christendom. David was perceived as the biblical predecessor to Christian Roman and Byzantine emperors and the name "New David" was used as an honorific reference to these rulers.[111] The Georgian Bagratids and the Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia claimed a direct biological descent from him.[112] Likewise, kings of the Frankish Carolingian dynasty frequently connected themselves to David; Charlemagne himself occasionally used the name of David as his pseudonym.[111]

Islam[edit]

David is an important figure in Islam as one of the major prophets sent by God to guide the Israelites. David is mentioned several times in the Quran with the Arabic name داود, Dāwūd, often with his son Solomon. In the Qur'an: David killed Goliath (2:251), a giant soldier in the Philistine army. When David killed Goliath, God granted him kingship and wisdom and enforced it (38:20). David was made God's "vicegerent on earth" (38:26) and God further gave David sound judgment (21:78; 37:21–24, 26) as well as the Psalms, regarded as books of divine wisdom (4:163; 17:55). The birds and mountains united with David in uttering praise to God (21:79; 34:10; 38:18), while God made iron soft for David (34:10), God also instructed David in the art of fashioning chain-mail out of iron (21:80); an indication of the first use of wrought iron, this knowledge gave David a major advantage over his bronze and cast iron-armed opponents, not to mention the cultural and economic impact. Together with Solomon, David gave judgment in a case of damage to the fields (21:78) and David judged the matter between two disputants in his prayer chamber (38:21–23). Since there is no mention in the Qur'an of the wrong David did to Uriah nor any reference to Bathsheba, Muslims reject this narrative.[113]

Muslim tradition and the hadith stress David's zeal in daily prayer as well as in fasting.[114] Qur'an commentators, historians and compilers of the numerous Stories of the Prophets elaborate upon David's concise Qur'anic narratives and specifically mention David's gift in singing his Psalms as well as his musical and vocal talents. His voice is described as having had a captivating power, weaving its influence not only over man but over all beasts and nature, who would unite with him to praise God.[115]

Art and literature[edit]

Literature[edit]

Literary works about David include:

- 1681–82 Dryden's long poem Absalom and Achitophel is an allegory that uses the story of the rebellion of Absalom against King David as the basis for his satire of the contemporary political situation, including events such as the Monmouth Rebellion (1685), the Popish Plot (1678) and the Exclusion Crisis.

- 1893 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle may have used the story of David and Bathsheba as a foundation for the Sherlock Holmes story The Adventure of the Crooked Man. Holmes mentions "the small affair of Uriah and Bathsheba" at the end of the story.[116]

- 1928 Elmer Davis's novel Giant Killer retells and embellishes the biblical story of David, casting David as primarily a poet who managed always to find others to do the "dirty work" of heroism and kingship. In the novel, Elhanan in fact killed Goliath but David claimed the credit; and Joab, David's cousin and general, took it upon himself to make many of the difficult decisions of war and statecraft when David vacillated or wrote poetry instead.

- 1936 William Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom! refers to the story of Absalom, David's son; his rebellion against his father and his death at the hands of David's general, Joab. In addition it parallels Absalom's vengeance for the rape of his sister Tamar by his half-brother, Amnon.

- 1946 Gladys Schmitt's novel David the King was a richly embellished biography of David's entire life. The book took a risk, especially for its time, in portraying David's relationship with Jonathan as overtly homoerotic, but was ultimately panned by critics as a bland rendition of the title character.

- 1966 Juan Bosch, a Dominican political leader and writer, wrote David: Biography of a King, as a realistic portrayal of David's life and political career.

- 1970 Dan Jacobson's The Rape of Tamar is an imagined account, by one of David's courtiers Yonadab, of the rape of Tamar by Amnon.

- 1972 Stefan Heym wrote The King David Report in which the historian Ethan compiles upon King Solomon's orders "a true and authoritative report on the life of David, Son of Jesse"—the East German writer's wry depiction of a court historian writing an "authorized" history, many incidents clearly intended as satirical references to the writer's own time.

- 1974 In Thomas Burnett Swann's biblical fantasy novel How are the Mighty Fallen, David and Jonathan are explicitly stated to be lovers. Moreover, Jonathan is a member of a winged semi-human race (possibly nephilim), one of several such races coexisting with humanity but often persecuted by it.

- 1980 Malachi Martin's factional novel King of Kings: A Novel of the Life of David relates the life of David, Adonai's champion in his battle with the Philistine deity Dagon.

- 1984 Joseph Heller wrote a novel based on David called God Knows, published by Simon & Schuster. Told from the perspective of an aging David, the humanity—rather than the heroism—of various biblical characters is emphasized. The portrayal of David as a man of flaws such as greed, lust, selfishness, and his alienation from God, the falling apart of his family is a distinctly 20th-century interpretation of the events told in the Bible.

- 1993 Madeleine L'Engle's novel Certain Women explores family, the Christian faith, and the nature of God through the story of King David's family and an analogous modern family's saga.

- 1995 Allan Massie wrote King David, a novel about David's career that portrays the king's relationship to Jonathan as sexual.[117]

- 2015 Geraldine Brooks wrote a novel about King David, The Secret Chord, told from the point of view of the prophet Nathan.[118][119]

Paintings[edit]

- 1599 Caravaggio David and Goliath

- 1616 Peter Paul Rubens David Slaying Goliath

- c. 1619 Caravaggio, David and Goliath

Sculptures[edit]

- 1440? Donatello, David

- 1473-75 Verrocchio, David

- 1501–04 Michelangelo, David

- 1623-24 Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David

Film[edit]

David has been depicted several times in films; these are some of the best-known:

- 1951 In David and Bathsheba, directed by Henry King, Gregory Peck played David.

- 1959 In Solomon and Sheba, directed by King Vidor, Finlay Currie played an aged King David.

- 1961 In A Story of David, directed by Bob McNaught, Jeff Chandler played David.

- 1985 In King David, directed by Bruce Beresford, Richard Gere played King David.

- 1996 In Dave and the Giant Pickle

Television[edit]

- 1976 The Story of David, a made-for-TV film with Timothy Bottoms and Keith Michell as King David at different ages.[120]

- 1997 David, a TV-film with Nathaniel Parker as King David and Leonard Nimoy as the Prophet Samuel.[121]

- 1997 Max von Sydow portrayed an older King David in the TV-film Solomon, a sequel to David.[122]

- 2009 Christopher Egan played David on Kings, a re-imagining loosely based on the biblical story.[123]

- King David is the focus of the second episode of History Channel's Battles BC documentary, which detailed all of his military exploits in the bible.[124]

- 2013 Langley Kirkwood portrayed King David in the miniseries The Bible.

- 2016 Of Kings and Prophets in which David is played by Olly Rix

Music[edit]

- The traditional birthday song Las Mañanitas mentions King David as the original singer in its lyrics.

- 1738 George Frideric Handel's oratorio Saul features David as one of its main characters.[125]

- 1921 Arthur Honegger's oratorio Le Roi David with a libretto by René Morax, instantly became a staple of the choral repertoire.

- 1964 Bob Dylan alludes to David in the last line of his song "When The Ship Comes In" ("And like Goliath, they'll be conquered").

- 1983 Bob Dylan refers to David in his song "Jokerman" ("Michelangelo indeed could've carved out your features").[126]

- 1984 Leonard Cohen's song "Hallelujah" has references to David ("there was a secret chord that David played and it pleased the Lord", "The baffled king composing Hallelujah") and Bathsheba ("you saw her bathing on the roof") in its opening verses.

- 1990 The song "One of the Broken" by Paddy McAloon, performed by Prefab Sprout on the album Jordan: The Comeback, has a reference to David ("I remember King David, with his harp and his beautiful, beautiful songs, I answered his prayers, and showed him a place where his music belongs").

- 1991 "Mad About You", a song on Sting's album The Soul Cages, explores David's obsession with Bathsheba from David's perspective.[127]

- 2000 The song "Gimme a Stone" appears on the Little Feat album Chinese Work Songs chronicles the duel with Goliath and contains a lament to Absalom as a bridge.[128]

Musical theater[edit]

- 1997 King David, sometimes described as a modern oratorio, with a book and lyrics by Tim Rice and music by Alan Menken.

Playing cards[edit]

For a considerable period, starting in the 15th century and continuing until the 19th, French playing card manufacturers assigned to each of the court cards names taken from history or mythology. In this context, the King of Spades was often known as "David".[129][130]

Image gallery[edit]

Rembrandt, c. 1650: Saul and David.

Mural of King David from an 18th-century sukkah (Jewish Museum of Franconia).

Miniature from the Paris Psalter: David in the robes of a Byzantine emperor.

Matteo Rosselli The triumphant David.

King David playing the harp, ceiling fresco from Monheim Town Hall, home of a wealthy Jewish merchant.

King David, stained glass windows from the Romanesque Augsburg Cathedral, late 11th century.

Study of King David, by Julia Margaret Cameron. Depicts Sir Henry Taylor, 1866.

Arnold Zadikow, 1930: The Young David displayed in the entrance of Berlin's Jewish Museum from 1933 until its loss during the Second World War.

David on an Israeli stamp

See also[edit]

- David and Jonathan

- David's Mighty Warriors

- David's Tomb

- Kings of Israel and Judah

- Large Stone Structure

- Midrash Shmuel (aggadah)

- Sons of David

Notes[edit]

- ^ (/ˈdeɪvɪd/; Hebrew: דָּוִד, Modern: Davīd, Tiberian: Dāwīḏ; Arabic: داود, Dāwūd; Koinē Greek: Δαυίδ, romanized: Dauíd; Latin: Davidus, David; Ge'ez: ዳዊት, Dawit; Old Armenian: Դաւիթ, Dawitʿ; Church Slavonic: Давíдъ, Davidŭ; possibly meaning "beloved one"[1])

- ^ Ancient Near East historians generally doubt that the united monarchy as described in the Bible existed.

References[edit]

- ^ G. Johannes Botterweck; Helmer Ringgren (1977). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-8028-2327-4.

- ^ https://biblehub.com/1_chronicles/28-3.htm

- ^ "JESSE'S SONS—How many sons did Jesse, King David's father, have? • ChristianAnswers.Net". christiananswers.net. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ "1 Chronicles 2:16 Their sisters were Zeruiah and Abigail. And the three sons of Zeruiah were Abishai, Joab, and Asahel". biblehub.com. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Bava Batra 91a

- ^ Lemaire, Andre (1999). In Hershel Shanks, ed., Ancient Israel: From Abraham to the Roman Destruction of the Temple. Biblical Archaeology Society; Revised edition, ISBN 978-1880317549

- ^ "1 Samuel 18:18". Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ^ "1 Samuel 18:19". Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ^ "1 Samuel 18:18-27". Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ^ Flavious Josephus (1998). "6.10.2". In Whiston, William (ed.). Antiquities of the Jews. Thomas Nelson.

- ^ "1 Samuel 25:14". Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ^ "2 Samuel 3:14". Archived from the original on 2018-08-17. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 3:1–3

- ^ 2 Samuel 5:14–16

- ^ According to the Dead Sea Scrolls and Greek version of 2 Samuel 13:21, "... he did not punish his son Amnon, because he loved him, for he was his firstborn." "2 Samuel 13 NLT". Bible Gateway. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ 1 Sam 13:8–14

- ^ 1 Sam 15:1–28

- ^ 1 Sam 16:1–13

- ^ 1 Sam 16:14–23

- ^ 1 Sam 17:1–11

- ^ 1 Sam 17:17–37

- ^ 1 Sam 17:38–39

- ^ 1 Sam 17:49–50

- ^ 1 Sam 17:55–56

- ^ 1 Sam 18:5–9

- ^ 1 Samuel 21:10–11

- ^ 1 Samuel 22:1

- ^ 1 Samuel 22:5

- ^ 1 Samuel 23:1–13

- ^ 1 Samuel 23:14

- ^ 1 Samuel 23:27–29

- ^ 1 Samuel 24:1–22

- ^ 1 Samuel 26:11

- ^ 1 Samuel 26:25, NIV text

- ^ cf. 1 Samuel 21:10–15

- ^ 1 Sam 29:1–11

- ^ 1 Samuel 30:1

- ^ 1 Sam 31:1–13

- ^ 2 Sam 2:1–4

- ^ 2 Sam 2:8–11

- ^ 2 Sam 5:1–3

- ^ 2 Sam 5:6–7

- ^ 2 Sam 6:1–12

- ^ 2 Sam 7:1–13

- ^ 2 Sam 7:16

- ^ 2 Sam 8:1–14

- ^ Lawrence O. Richards (2002). Bible Reader's Companion. David C Cook. pp. 210–. ISBN 978-0-7814-3879-7. Archived from the original on 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ^ Carlos Wilton (June 2004). Lectionary Preaching Workbook: For All Users of the Revised Common, the Roman Catholic, and the Episcopal Lectionaries. Series VIII. CSS Publishing. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-0-7880-2371-2.

- ^ David J. Zucker (10 December 2013). The Bible's Prophets: An Introduction for Christians and Jews. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-1-63087-102-4.

- ^ "2 Samuel 11:2-4". Archived from the original on 2018-12-02. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ Antony F. Campbell (2005). 2 Samuel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-0-8028-2813-2.

- ^ Sara M. Koenig (8 November 2011). Isn't This Bathsheba?: A Study in Characterization. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-60899-427-4.

- ^ Antony F. Campbell (2004). Joshua to Chronicles: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-0-664-25751-4. Archived from the original on 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- ^ 2 Sam 11:14–17

- ^ Some commentators believe this meant during David's lifetime Archived 2017-08-01 at the Wayback Machine. Others say it included his posterity Archived 2017-07-29 at the Wayback Machine. 2 Sam 12:8-12:10

- ^ 2 Samuel 12:13

- ^ Adultery was a capital crime under Mosaic law: Leviticus 20:10

- ^ 2 Samuel 12:14: NIV translation

- ^ 2 Sam 15:1–12

- ^ 2 Sam 18:1–15

- ^ 2 Sam 18:33

- ^ Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges Archived 2017-07-31 at the Wayback Machine on 2 Samuel 19, accessed 12 August 2017

- ^ 2 Samuel 19:1–8

- ^ 2 Samuel 19:15–17

- ^ 1 Kings 1:1–5

- ^ 1 Kings 1:11–31

- ^ 2 Sam 5:4

- ^ 1 Kings 2:1–9

- ^ Helen C. Evans; William W. Wixom, eds. (5 March 1997). The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 86. ISBN 9780870997778. Retrieved 5 March 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ 1 Samuel 16:15–18

- ^ Other translations say, "the hero of Israel's songs," "the favorite singer of Israel," "the contented psalm writer of Israel," and "Israel's beloved singer of songs." 2 Samuel 23:1 Archived 2017-07-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Commentary on II Samuel 22, The Anchor Bible, Vol. 9. II Samuel. P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., 1984. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-06808-5

- ^ a b Steven McKenzie, Associate Professor Rhodes College, Memphis, Tennessee Archived 2012-06-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Psalm 34, Interlinear NIV Hebrew-English Old Testament, Kohlenberger, J.R, 1987. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House ISBN 0-310-40200-X

- ^ 1 Samuel 21:15

- ^ a b Pioske 2015, p. 180.

- ^

Pioske, Daniel (2015-02-11). "4: David's Jerusalem: The Early 10th Century BCE Part I: An Agrarian Community". David's Jerusalem: Between Memory and History. Routledge Studies in Religion. 45. Routledge (published 2015). p. 180. ISBN 9781317548911. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

[...] the reading of bytdwd as "House of David" has been challenged by those unconvinced of the inscription's allusion to an eponymous David or the kingdom of Judah.

- ^ Pioske 2015, p. 210, fn.18.

- ^ a b McKenzei, Steven L. "King David: A Biography (excerpt)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-01-19. Retrieved 2018-06-19. 2000

- ^ Hill, Andrew E.; Walton, John H. (2009) [1991]. A Survey of the Old Testament (3rd ed.). Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-310-28095-8.

The events of the book took place in the last half of the eleventh century and the early part of the tenth century BC, but it is difficult to determine when the events were recorded. There are no particularly persuasive reasons to date the sources used by the compiler later than the events themselves, and good reason to believe that contemporary records were kept (cf. 2 Sam. 20:24–25).

- ^ Auld 2003, p. 219.

- ^ Knight 1991, p. 853.

- ^ McKenzie 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Moore & Kelle 2011, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Finkelstein & Silberman 2007, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Moore & Kelle 2011, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton University Press, 1992 pp. 301–307.

- ^ Thompson TL. "A View from Copenhagen: Israel and the History of Palestine". Archived from the original on 2012-10-29. Retrieved 2012-11-03.

- ^ Mazar A. Archaeology and the biblical Narrative: The Case of the United Monarchy (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11.

- ^ Baruch Halpern, "David's Secret Demons", 2001. Review of Baruch Halpern's "David's Secret Demons" Archived 2007-08-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Finkelstein and Silberman, "David and Solomon", 2006. See review "Archaeology" magazine Archived 2007-11-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Baden, Joel (2014-07-29). The Historical David: The Real Life of an Invented Hero. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 9780062188373.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002) [2001]. "8. In the Shadow of Empire (842–720 BCE)". The Bible Unearthed. Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and The Origin of Its Sacred Texts (First Touchstone Edition 2002 ed.). New York: Touchstone. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-684-86913-1.

Archaeologically and historically, the redating of these cities from Solomon's era to the time of Omrides has enormous implication. It removes the only archeological evidence that there was ever a united monarchy based in Jerusalem and suggests that David and Solomon were, in political terms, little more than hill country chieftains, whose administrative reach remained on a fairly local level, restricted to the hill country.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein; Neil Asher Silberman (6 March 2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. pp. 23, 241–247. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein; Neil Asher Silberman (6 March 2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

we still have no hard archaeological evidence—despite the unparalleled biblical description of its grandeur—that Jerusalem was anything more than a modest highland village in the time of David, Solomon, and Rehoboam.

- ^ "Table Two" (Finklestein and Silberman, 2002: 131).

- ^ Speaking of Samaria: "The scale of this project was enormous." (Finkelstein and Silberman 2002: 181).

- ^ "David, King of Judah (Not Israel)". bibleinterp.com. July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ "David". jewishencyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-11. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin. p. 107a.

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ Zohar Bereishis 91b

- ^ "King David". 2008-10-28. Archived from the original on 2019-04-20. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ^ "David - OrthodoxWiki". Archived from the original on 2019-05-28. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ^ "David" Archived 2009-08-19 at the Wayback Machine article from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ John Corbett (1911) King David Archived 2007-09-25 at the Wayback Machine The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company)

- ^ McManners, John (2001-03-15). The Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. p. 101. ISBN 9780192854391. Archived from the original on 2016-02-09. Retrieved 2016-01-07.

- ^ Saint of the Day Archived 2008-05-30 at the Wayback Machine for December 29 at St. Patrick Catholic Church, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Lindsay of the Mount, Sir David (1542). Lindsay of the Mount Roll. Edinburgh, W. & D. Laing. Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ^ a b Garipzanov, Ildar H. (2008). The Symbolic Language of Royal Authority in the Carolingian World (c. 751–877). Brill. pp. 128, 225. ISBN 978-9004166691.

- ^ Rapp, Stephen H., Jr. (1997). Imagining History at the Crossroads: Persia, Byzantium, and the Architects of the Written Georgian Past. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan. p. 528.

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon M. (The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism, "David"

- ^ "Dawud". Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ Stories of the Prophets, Ibn Kathir, "Story of David"

- ^ DK (1 October 2015). The Sherlock Holmes Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained. Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 9780241248331. Retrieved 12 February 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ O'Kane, Martin (1999). "The Biblical King David and His Artistic and Literary Afterlives". In Exum, Jo Cheryl (ed.). Beyond the Biblical Horizon: The Bible and the Arts. p. 86. ISBN 978-9004112902. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Gilbert, Matthew (3 October 2015). "'The Secret Chord' by Geraldine Brooks". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ Hoffman, Alice (28 September 2015). "Geraldine Brooks reimagines King David's life in 'The Secret Chord'". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Burnette-Bletsch, Rhonda (12 September 2016). The Bible in Motion: A Handbook of the Bible and Its Reception in Film. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9781614513261. Retrieved 2 September 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Roberts, Jerry (5 June 2009). Encyclopedia of Television Film Directors. Scarecrow Press. p. 368. ISBN 9780810863781. Retrieved 14 February 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey (1 September 2008). Hollywood's Ancient Worlds. A&C Black. p. 168. ISBN 9781847250070. Retrieved 14 February 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "David, My David". Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Battles BC

- ^ "G. F. Handel's Compositions". The Handel Institute. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ Rogovoy, Seth (24 November 2009). Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet. Simon and Schuster. p. 237. ISBN 9781416559832. Retrieved 14 February 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Mad About You". Sting.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Lyrics Database". Little Feat website. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- ^ "snopes.com: Four Kings in Deck of Cards". snopes.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-18. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ "Courts on playing cards" Archived 2012-02-18 at WebCite, by David Madore, with illustrations of the Anglo-American and French court cards

Further reading[edit]

- Alexander, David; Alexander, Pat, eds. (1983). Eerdmans' Handbook to the Bible (New rev. ed.). Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3486-7.

- Auld, Graeme (2003). "1 & 2 Samuel". In James D. G. Dunn and John William Rogerson (ed.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bergen, David T. (1996). 1, 2 Samuel. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9780805401073.

- Breytenbach, Andries (2000). "Who Is Behind The Samuel Narrative?". In Johannes Cornelis de Moor and H.F. Van Rooy (ed.). Past, Present, Future: The Deuteronomistic History and the Prophets. Brill. ISBN 978-9004118713.

- Brettler, Mark Zvi (2007). "Introduction to the Historical Books". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bright, John (1981). A History of Israel (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Westminster Press. ISBN 978-0-664-21381-7.

- Bruce, F. F. (1963). Israel and the Nations: From the Exodus to the Fall of the Second Temple. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. OCLC 1026642167.

- Coogan, Michael D. (2009) A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: the Hebrew Bible in its Context Oxford University Press ISBN 9780199740291

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). "Cultural Contexts: The Ancient Near East and Israel". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dever, William G. (2001) What did the Bible writers know and when did they know it? William B. Eerdmans Publ. Co., Cambridge UK.

- Dick, Michael B (2004). "The History of 'David's Rise to Power' and the Neo-Babylonian Succession Apologies". In Bernard Frank Batto and Kathryn L. Roberts (ed.). David and Zion: biblical studies in honor of J.J.M. Roberts. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060927.

- Eynikel, Erik (2000). "The Relation Between the Eli Narrative and the Ark Narratives". In Johannes Cornelis de Moor and H.F. Van Rooy (ed.). Past, present, future: the Deuteronomistic History and the Prophets. Brill. ISBN 978-9004118713.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2007). David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743243636.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fridman, Julia (February 20, 2014). "The Naked Truth About King David, the 8th Son". Haaretz.

- Gordon, Robert (1986). I & II Samuel, A Commentary. Paternoster Press. ISBN 9780310230229.

- Green, Adam (2007). King Saul: The True History of the First Messiah. Cambridge, UK: Lutterworth Press. ISBN 978-0718830748.

- Halpern, Baruch (2000). "David". In Freedman, David Noel; Allen C., Myers (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halpern, Baruch (2001). David's Secret Demons: Messiah, Murderer, Traitor, King. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802827975.

- Harrison, R. K. (1969). An Introduction to the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. OCLC 814408043.

- Hertzberg, Hans Wilhelm (1964). I & II Samuel, A Commentary (trans. from German 1960 2nd ed.). Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664223182.

- Jones, Gwilym H (2001). "1 and 2 Samuel". In John Barton and John Muddiman (ed.). The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- Kidner, Derek (1973). The Psalms. Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press. ISBN 978-0-87784-868-4.

- Kirsch, Jonathan (2000) King David: the real life of the man who ruled Israel. Ballantine. ISBN 0-345-43275-4.

- Klein, R.W. (2003). "Samuel, Books of". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W (ed.). The international standard Bible encyclopedia. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837844.

- Knight, Douglas A (1995). "Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomists". In James Luther Mays, David L. Petersen and Kent Harold Richards (ed.). Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567292896.

- Knight, Douglas A (1991). "Sources". In Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard (ed.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKenzie, Steven L. (2004). Abingdon Old Testament Commentaries: I & II Chronicles. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426759802.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Noll, K. L. (1997). The Faces of David. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Acad. Press. ISBN 978-1-85075-659-0.

- Pioske, Daniel (2015). David's Jerusalem: Between Memory and History. Routledge. ISBN 9781317548911.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pfoh, Emanuel (2016). The Emergence of Israel in Ancient Palestine: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 9781134947751.

- Rosner, Steven (2012). A Guide to the Psalms of David. Outskirts Press.

- Schleffer, Eben (2000). "Saving Saul from the Deuteronomist". In Johannes Cornelis de Moor and H.F. Van Rooy (ed.). Past, Present, Future: The Deuteronomistic History and the Prophets. Brill. ISBN 978-9004118713.

- Soggin, Alberto (1987). Introduction to the Old Testament. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664221560.

- Spieckerman, Hermann (2001). "The Deuteronomistic History". In Leo G. Perdue (ed.). The Blackwell companion to the Hebrew Bible. Blackwell. ISBN 9780631210719.

- Thompson, J. A. (1986). Handbook of Life in Bible Times. Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity Press. ISBN 978-0-87784-949-0.

- Tsumura, David Toshio (2007). The First Book of Samuel. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802823595.

- Van Seters, John (1997). In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060132.

- Walton, John H (2009). "The Deuteronomistic History". In Andrew E. Hill, John H. Walton (ed.). A Survey of the Old Testament. Zondervan. ISBN 9780631210719.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to David (Biblical figure). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: David |

- Complete Bible Genealogy—David's family tree

- David engravings from the De Verda collection

- King David at the Christian Iconography web site

- The History of David, by William Caxton

- Prophets of the Hebrew Bible

- David

- 10th-century BC biblical rulers

- 11th-century BC biblical rulers

- 11th-century BC Kings of Israel (united monarchy)

- 10th-century BC Kings of Israel (united monarchy)

- Ancient history of Jerusalem

- Angelic visionaries

- Bathsheba

- Biblical murderers

- Books of Samuel

- Christian saints from the Old Testament

- Harpists

- Hebrew Bible people

- Jewish poets

- Jewish monarchs

- Kings of ancient Israel

- Kings of ancient Judah

- People from Bethlehem

- Roman Catholic royal saints

- Shepherds

- Warlords