Arabic

Arabic (اَلْعَرَبِيَّةُ, al-ʿarabiyyah, [al ʕaraˈbijːa] (![]() listen) or عَرَبِيّ, ʿarabīy, [ˈʕarabiː] (

listen) or عَرَبِيّ, ʿarabīy, [ˈʕarabiː] (![]() listen) or [ʕaraˈbij]) is a Semitic language that first emerged in the 1st to 4th centuries CE.[5] It is now the lingua franca of the Arab world.[6] It is named after the Arabs, a term initially used to describe peoples living in the area bounded by Mesopotamia in the east and the Anti-Lebanon mountains in the west, in Northwestern Arabia and in the Sinai Peninsula.[7] The ISO assigns language codes to thirty varieties of Arabic, including its standard form, Modern Standard Arabic,[8] also referred to as Literary Arabic, which is modernized Classical Arabic. This distinction exists primarily among Western linguists; Arabic speakers themselves generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic, but rather refer to both as al-ʿarabiyyatu l-fuṣḥā (اَلعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ,[9] "the purest Arabic") or simply al-fuṣḥā (اَلْفُصْحَىٰ).

listen) or [ʕaraˈbij]) is a Semitic language that first emerged in the 1st to 4th centuries CE.[5] It is now the lingua franca of the Arab world.[6] It is named after the Arabs, a term initially used to describe peoples living in the area bounded by Mesopotamia in the east and the Anti-Lebanon mountains in the west, in Northwestern Arabia and in the Sinai Peninsula.[7] The ISO assigns language codes to thirty varieties of Arabic, including its standard form, Modern Standard Arabic,[8] also referred to as Literary Arabic, which is modernized Classical Arabic. This distinction exists primarily among Western linguists; Arabic speakers themselves generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic, but rather refer to both as al-ʿarabiyyatu l-fuṣḥā (اَلعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ,[9] "the purest Arabic") or simply al-fuṣḥā (اَلْفُصْحَىٰ).

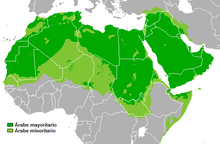

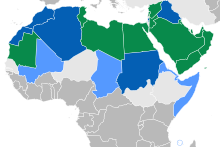

Arabic is widely taught in schools and universities and is used to varying degrees in workplaces, government and the media. Arabic, in its standard form, is the official language of 26 states, as well as the liturgical language of the religion of Islam, since the Quran and Hadith were written in Arabic.

During the Middle Ages, Arabic was a major vehicle of culture in Europe, especially in science, mathematics and philosophy. As a result, many European languages have also borrowed many words from it. Arabic influence, mainly in vocabulary, is seen in European languages—mainly Spanish and to a lesser extent Portuguese and Catalan—owing to both the proximity of Christian European and Muslim Arab civilizations and the long-lasting Arabic culture and language presence mainly in Southern Iberia during the Al-Andalus era. Sicilian has about 500 Arabic words, many of which relate to agriculture and related activities,[10][full citation needed] as a legacy of the Emirate of Sicily from the mid-9th to mid-10th centuries, while Maltese language is a Semitic language developed from a dialect of Arabic and written in the Latin alphabet.[11] The Balkan languages, including Greek and Bulgarian, have also acquired a significant number of Arabic words through contact with Ottoman Turkish.

Arabic has influenced many other languages around the globe throughout its history. Some of the most influenced languages are Persian, Turkish, Hindustani (Hindi and Urdu), Kashmiri, Kurdish, Bosnian, Kazakh, Bengali, Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), Maldivian, Pashto, Punjabi, Albanian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Sicilian, Spanish, Greek, Bulgarian, Tagalog, Assamese, Sindhi, Odia[12] and Hausa and some languages in parts of Africa. Conversely, Arabic has borrowed words from other languages, including Hebrew, Greek, Aramaic, and Persian in medieval times and languages such as English and French in modern times.

Arabic is the liturgical language of 1.8 billion Muslims, and Arabic[13] is one of six official languages of the United Nations.[14][15][16][17] All varieties of Arabic combined are spoken by perhaps as many as 422 million speakers (native and non-native) in the Arab world,[18] making it the fifth most spoken language in the world. Arabic is written with the Arabic alphabet, which is an abjad script and is written from right to left, although the spoken varieties are sometimes written in ASCII Latin from left to right with no standardized orthography.

Classification

Arabic is usually, but not universally, classified as a Central Semitic language. It is related to languages in other subgroups of the Semitic language group (Northwest Semitic, South Semitic, East Semitic, West Semitic), such as Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, Ugaritic, Phoenician, Canaanite, Amorite, Ammonite, Eblaite, epigraphic Ancient North Arabian, epigrahic Ancient South Arabian, Ethiopic, Modern South Arabian, and numerous other dead and modern languages. Linguists still differ as to the best classification of Semitic language sub-groups.[5] The Semitic languages changed a great deal between Proto-Semitic and the emergence of the Central Semitic languages, particularly in grammar. Innovations of the Central Semitic languages—all maintained in Arabic—include:

- The conversion of the suffix-conjugated stative formation (jalas-) into a past tense.

- The conversion of the prefix-conjugated preterite-tense formation (yajlis-) into a present tense.

- The elimination of other prefix-conjugated mood/aspect forms (e.g., a present tense formed by doubling the middle root, a perfect formed by infixing a /t/ after the first root consonant, probably a jussive formed by a stress shift) in favor of new moods formed by endings attached to the prefix-conjugation forms (e.g., -u for indicative, -a for subjunctive, no ending for jussive, -an or -anna for energetic).

- The development of an internal passive.

There are several features which Classical Arabic, the modern Arabic varieties, as well as the Safaitic and Hismaic inscriptions share which are unattested in any other Central Semitic language variety, including the Dadanitic and Taymanitic languages of the northern Hejaz. These features are evidence of common descent from a hypothetical ancestor, Proto-Arabic. The following features can be reconstructed with confidence for Proto-Arabic:[19]

- negative particles m *mā; lʾn *lā-ʾan > CAr lan

- mafʿūl G-passive participle

- prepositions and adverbs f, ʿn, ʿnd, ḥt, ʿkdy

- a subjunctive in -a

- t-demonstratives

- leveling of the -at allomorph of the feminine ending

- ʾn complementizer and subordinator

- the use of f- to introduce modal clauses

- independent object pronoun in (ʾ)y

- vestiges of nunation

History

Old Arabic

Arabia boasted a wide variety of Semitic languages in antiquity. In the southwest, various Central Semitic languages both belonging to and outside of the Ancient South Arabian family (e.g. Southern Thamudic) were spoken. It is also believed that the ancestors of the Modern South Arabian languages (non-Central Semitic languages) were also spoken in southern Arabia at this time. To the north, in the oases of northern Hejaz, Dadanitic and Taymanitic held some prestige as inscriptional languages. In Najd and parts of western Arabia, a language known to scholars as Thamudic C is attested. In eastern Arabia, inscriptions in a script derived from ASA attest to a language known as Hasaitic. Finally, on the northwestern frontier of Arabia, various languages known to scholars as Thamudic B, Thamudic D, Safaitic, and Hismaic are attested. The last two share important isoglosses with later forms of Arabic, leading scholars to theorize that Safaitic and Hismaic are in fact early forms of Arabic and that they should be considered Old Arabic.[20]

Linguists generally believe that "Old Arabic" (a collection of related dialects that constitute the precursor of Arabic) first emerged around the 1st century CE. Previously, the earliest attestation of Old Arabic was thought to be a single 1st century CE inscription in Sabaic script at Qaryat Al-Faw, in southern present-day Saudi Arabia. However, this inscription does not participate in several of the key innovations of the Arabic language group, such as the conversion of Semitic mimation to nunation in the singular. It is best reassessed as a separate language on the Central Semitic dialect continuum.[21]

It was also thought that Old Arabic coexisted alongside—and then gradually displaced--epigraphic Ancient North Arabian (ANA), which was theorized to have been the regional tongue for many centuries. ANA, despite its name, was considered a very distinct language, and mutually unintelligible, from "Arabic". Scholars named its variant dialects after the towns where the inscriptions were discovered (Dadanitic, Taymanitic, Hismaic, Safaitic).[5] However, most arguments for a single ANA language or language family were based on the shape of the definite article, a prefixed h-. It has been argued that the h- is an archaism and not a shared innovation, and thus unsuitable for language classification, rendering the hypothesis of an ANA language family untenable.[22] Safaitic and Hismaic, previously considered ANA, should be considered Old Arabic due to the fact that they participate in the innovations common to all forms of Arabic.[20]

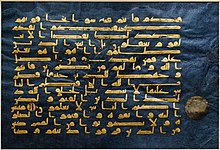

The earliest attestation of continuous Arabic text in an ancestor of the modern Arabic script are three lines of poetry by a man named Garm(')allāhe found in En Avdat, Israel, and dated to around 125 CE.[23] This is followed by the epitaph of the Lakhmid king Mar 'al-Qays bar 'Amro, dating to 328 CE, found at Namaraa, Syria. From the 4th to the 6th centuries, the Nabataean script evolves into the Arabic script recognizable from the early Islamic era.[24] There are inscriptions in an undotted, 17-letter Arabic script dating to the 6th century CE, found at four locations in Syria (Zabad, Jabal ‘Usays, Harran, Umm al-Jimaal). The oldest surviving papyrus in Arabic dates to 643 CE, and it uses dots to produce the modern 28-letter Arabic alphabet. The language of that papyrus and of the Qur'an are referred to by linguists as "Quranic Arabic", as distinct from its codification soon thereafter into "Classical Arabic".[5]

Old Hejazi and Classical Arabic

In late pre-Islamic times, a transdialectal and transcommunal variety of Arabic emerged in the Hejaz which continued living its parallel life after literary Arabic had been institutionally standardized in the 2nd and 3rd century of the Hijra, most strongly in Judeo-Christian texts, keeping alive ancient features eliminated from the "learned" tradition (Classical Arabic).[25] This variety and both its classicizing and "lay" iterations have been termed Middle Arabic in the past, but they are thought to continue an Old Higazi register. It is clear that the orthography of the Qur'an was not developed for the standardized form of Classical Arabic; rather, it shows the attempt on the part of writers to record an archaic form of Old Higazi.

In the late 6th century AD, a relatively uniform intertribal "poetic koine" distinct from the spoken vernaculars developed based on the Bedouin dialects of Najd, probably in connection with the court of al-Ḥīra. During the first Islamic century, the majority of Arabic poets and Arabic-writing persons spoke Arabic as their mother tongue. Their texts, although mainly preserved in far later manuscripts, contain traces of non-standardized Classical Arabic elements in morphology and syntax. The standardization of Classical Arabic reached completion around the end of the 8th century. The first comprehensive description of the ʿarabiyya "Arabic", Sībawayhi's al-Kitāb, is based first of all upon a corpus of poetic texts, in addition to Qur'an usage and Bedouin informants whom he considered to be reliable speakers of the ʿarabiyya.[26] By the 8th century, knowledge of Classical Arabic had become an essential prerequisite for rising into the higher classes throughout the Islamic world.

Neo-Arabic

Charles Ferguson's koine theory (Ferguson 1959) claims that the modern Arabic dialects collectively descend from a single military koine that sprang up during the Islamic conquests; this view has been challenged in recent times. Ahmad al-Jallad proposes that there were at least two considerably distinct types of Arabic on the eve of the conquests: Northern and Central (Al-Jallad 2009). The modern dialects emerged from a new contact situation produced following the conquests. Instead of the emergence of a single or multiple koines, the dialects contain several sedimentary layers of borrowed and areal features, which they absorbed at different points in their linguistic histories.[26] According to Veersteegh and Bickerton, colloquial Arabic dialects arose from pidginized Arabic formed from contact between Arabs and conquered peoples. Pidginization and subsequent creolization among Arabs and arabized peoples could explain relative morphological and phonological simplicity of vernacular Arabic compared to Classical and MSA.[27][28]

In around the 11th and 12th centuries in al-Andalus, the zajal and muwashah poetry forms developed in the dialectical Arabic of Cordoba and the Maghreb.[29]

Nahda

In the wake of the industrial revolution and European hegemony and colonialism, pioneering Arabic presses, such as the Amiri Press established by Muhammad Ali (1819), dramatically changed the diffusion and consumption of Arabic literature and publications.[32]

The Nahda cultural renaissance saw the creation of a number of Arabic academies modeled after the Académie française, starting with the Arab Academy of Damascus (1918), which aimed to develop the Arabic lexicon to suit these transformations.[33] This gave rise to what Western scholars call Modern Standard Arabic.

Classical, Modern Standard and spoken Arabic

Arabic usually refers to Standard Arabic, which Western linguists divide into Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic.[34] It could also refer to any of a variety of regional vernacular Arabic dialects, which are not necessarily mutually intelligible.

Classical Arabic is the language found in the Quran, used from the period of Pre-Islamic Arabia to that of the Abbasid Caliphate. Classical Arabic is prescriptive, according to the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh) and the vocabulary defined in classical dictionaries (such as the Lisān al-ʻArab).

Modern Standard Arabic largely follows the grammatical standards of Classical Arabic and uses much of the same vocabulary. However, it has discarded some grammatical constructions and vocabulary that no longer have any counterpart in the spoken varieties and has adopted certain new constructions and vocabulary from the spoken varieties. Much of the new vocabulary is used to denote concepts that have arisen in the industrial and post-industrial era, especially in modern times. Due to its grounding in Classical Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic is removed over a millennium from everyday speech, which is construed as a multitude of dialects of this language. These dialects and Modern Standard Arabic are described by some scholars as not mutually comprehensible. The former are usually acquired in families, while the latter is taught in formal education settings. However, there have been studies reporting some degree of comprehension of stories told in the standard variety among preschool-aged children.[35] The relation between Modern Standard Arabic and these dialects is sometimes compared to that of Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin vernaculars (which became Romance languages) in medieval and early modern Europe.[36] This view though does not take into account the widespread use of Modern Standard Arabic as a medium of audiovisual communication in today's mass media—a function Latin has never performed.

MSA is the variety used in most current, printed Arabic publications, spoken by some of the Arabic media across North Africa and the Middle East, and understood by most educated Arabic speakers. "Literary Arabic" and "Standard Arabic" (فُصْحَى fuṣḥá) are less strictly defined terms that may refer to Modern Standard Arabic or Classical Arabic.

Some of the differences between Classical Arabic (CA) and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) are as follows:

- Certain grammatical constructions of CA that have no counterpart in any modern vernacular dialect (e.g., the energetic mood) are almost never used in Modern Standard Arabic.

- Case distinctions are very rare in Arabic vernaculars. As a result, MSA is generally composed without case distinctions in mind, and the proper cases are added after the fact, when necessary. Because most case endings are noted using final short vowels, which are normally left unwritten in the Arabic script, it is unnecessary to determine the proper case of most words. The practical result of this is that MSA, like English and Standard Chinese, is written in a strongly determined word order and alternative orders that were used in CA for emphasis are rare. In addition, because of the lack of case marking in the spoken varieties, most speakers cannot consistently use the correct endings in extemporaneous speech. As a result, spoken MSA tends to drop or regularize the endings except when reading from a prepared text.

- The numeral system in CA is complex and heavily tied in with the case system. This system is never used in MSA, even in the most formal of circumstances; instead, a significantly simplified system is used, approximating the system of the conservative spoken varieties.

MSA uses much Classical vocabulary (e.g., dhahaba 'to go') that is not present in the spoken varieties, but deletes Classical words that sound obsolete in MSA. In addition, MSA has borrowed or coined many terms for concepts that did not exist in Quranic times, and MSA continues to evolve.[37] Some words have been borrowed from other languages—notice that transliteration mainly indicates spelling and not real pronunciation (e.g., فِلْم film 'film' or ديمقراطية dīmuqrāṭiyyah 'democracy').

However, the current preference is to avoid direct borrowings, preferring to either use loan translations (e.g., فرع farʻ 'branch', also used for the branch of a company or organization; جناح janāḥ 'wing', is also used for the wing of an airplane, building, air force, etc.), or to coin new words using forms within existing roots (استماتة istimātah 'apoptosis', using the root موت m/w/t 'death' put into the Xth form, or جامعة jāmiʻah 'university', based on جمع jamaʻa 'to gather, unite'; جمهورية jumhūriyyah 'republic', based on جمهور jumhūr 'multitude'). An earlier tendency was to redefine an older word although this has fallen into disuse (e.g., هاتف hātif 'telephone' < 'invisible caller (in Sufism)'; جريدة jarīdah 'newspaper' < 'palm-leaf stalk').

Colloquial or dialectal Arabic refers to the many national or regional varieties which constitute the everyday spoken language and evolved from Classical Arabic. Colloquial Arabic has many regional variants; geographically distant varieties usually differ enough to be mutually unintelligible, and some linguists consider them distinct languages.[38] The varieties are typically unwritten. They are often used in informal spoken media, such as soap operas and talk shows,[39] as well as occasionally in certain forms of written media such as poetry and printed advertising.

The only variety of modern Arabic to have acquired official language status is Maltese, which is spoken in (predominantly Catholic) Malta and written with the Latin script. It is descended from Classical Arabic through Siculo-Arabic, but is not mutually intelligible with any other variety of Arabic. Most linguists list it as a separate language rather than as a dialect of Arabic.

Even during Muhammad's lifetime, there were dialects of spoken Arabic. Muhammad spoke in the dialect of Mecca, in the western Arabian peninsula, and it was in this dialect that the Quran was written down. However, the dialects of the eastern Arabian peninsula were considered the most prestigious at the time, so the language of the Quran was ultimately converted to follow the eastern phonology. It is this phonology that underlies the modern pronunciation of Classical Arabic. The phonological differences between these two dialects account for some of the complexities of Arabic writing, most notably the writing of the glottal stop or hamzah (which was preserved in the eastern dialects but lost in western speech) and the use of alif maqṣūrah (representing a sound preserved in the western dialects but merged with ā in eastern speech).[citation needed]

Language and dialect

The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia, which is the normal use of two separate varieties of the same language, usually in different social situations. Tawleed is the process of giving a new shade of meaning to an old classical word. For example, al-hatif lexicographically, means the one whose sound is heard but whose person remains unseen. Now the term al-hatif is used for a telephone. Therefore, the process of tawleed can express the needs of modern civilization in a manner that would appear to be originally Arabic.[40] In the case of Arabic, educated Arabs of any nationality can be assumed to speak both their school-taught Standard Arabic as well as their native, mutually unintelligible "dialects";[41][42][43][44][45] these dialects linguistically constitute separate languages which may have dialects of their own.[46] When educated Arabs of different dialects engage in conversation (for example, a Moroccan speaking with a Lebanese), many speakers code-switch back and forth between the dialectal and standard varieties of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence. Arabic speakers often improve their familiarity with other dialects via music or film.

The issue of whether Arabic is one language or many languages is politically charged, in the same way it is for the varieties of Chinese, Hindi and Urdu, Serbian and Croatian, Scots and English, etc. In contrast to speakers of Hindi and Urdu who claim they cannot understand each other even when they can, speakers of the varieties of Arabic will claim they can all understand each other even when they cannot.[47] The issue of diglossia between spoken and written language is a significant complicating factor: A single written form, significantly different from any of the spoken varieties learned natively, unites a number of sometimes divergent spoken forms. For political reasons, Arabs mostly assert that they all speak a single language, despite significant issues of mutual incomprehensibility among differing spoken versions.[48]

From a linguistic standpoint, it is often said that the various spoken varieties of Arabic differ among each other collectively about as much as the Romance languages.[49] This is an apt comparison in a number of ways. The period of divergence from a single spoken form is similar—perhaps 1500 years for Arabic, 2000 years for the Romance languages. Also, while it is comprehensible to people from the Maghreb, a linguistically innovative variety such as Moroccan Arabic is essentially incomprehensible to Arabs from the Mashriq, much as French is incomprehensible to Spanish or Italian speakers but relatively easily learned by them. This suggests that the spoken varieties may linguistically be considered separate languages.

Influence of Arabic on other languages

The influence of Arabic has been most important in Islamic countries, because it is the language of the Islamic sacred book, the Quran. Arabic is also an important source of vocabulary for languages such as Amharic, Azerbaijani, Baluchi, Bengali, Berber, Bosnian, Chaldean, Chechen, Chittagonian, Croatian, Dagestani, English, German, Gujarati, Hausa, Hindi, Kazakh, Kurdish, Kutchi, Kyrgyz, Malay (Malaysian and Indonesian), Pashto, Persian, Punjabi, Rohingya, Romance languages (French, Catalan, Italian, Portuguese, Sicilian, Spanish, etc.) Saraiki, Sindhi, Somali, Sylheti, Swahili, Tagalog, Tigrinya, Turkish, Turkmen, Urdu, Uyghur, Uzbek, Visayan and Wolof, as well as other languages in countries where these languages are spoken.[citation needed] The Education Minister of France has recently been emphasizing the learning and usage of Arabic in their schools.[50]

In addition, English has many Arabic loanwords, some directly, but most via other Mediterranean languages. Examples of such words include admiral, adobe, alchemy, alcohol, algebra, algorithm, alkaline, almanac, amber, arsenal, assassin, candy, carat, cipher, coffee, cotton, ghoul, hazard, jar, kismet, lemon, loofah, magazine, mattress, sherbet, sofa, sumac, tariff, and zenith.[51] Other languages such as Maltese[52] and Kinubi derive ultimately from Arabic, rather than merely borrowing vocabulary or grammatical rules.

Terms borrowed range from religious terminology (like Berber taẓallit, "prayer", from salat (صلاة ṣalāh)), academic terms (like Uyghur mentiq, "logic"), and economic items (like English coffee) to placeholders (like Spanish fulano, "so-and-so"), everyday terms (like Hindustani lekin, "but", or Spanish taza and French tasse, meaning "cup"), and expressions (like Catalan a betzef, "galore, in quantity"). Most Berber varieties (such as Kabyle), along with Swahili, borrow some numbers from Arabic. Most Islamic religious terms are direct borrowings from Arabic, such as صلاة (salat), "prayer", and إمام (imam), "prayer leader."

In languages not directly in contact with the Arab world, Arabic loanwords are often transferred indirectly via other languages rather than being transferred directly from Arabic. For example, most Arabic loanwords in Hindustani and Turkish entered though Persian is an Indo-Iranian language. Older Arabic loanwords in Hausa were borrowed from Kanuri.

Arabic words also made their way into several West African languages as Islam spread across the Sahara. Variants of Arabic words such as كتاب kitāb ("book") have spread to the languages of African groups who had no direct contact with Arab traders.[53]

Since throughout the Islamic world, Arabic occupied a position similar to that of Latin in Europe, many of the Arabic concepts in the fields of science, philosophy, commerce, etc. were coined from Arabic roots by non-native Arabic speakers, notably by Aramaic and Persian translators, and then found their way into other languages. This process of using Arabic roots, especially in Kurdish and Persian, to translate foreign concepts continued through to the 18th and 19th centuries, when swaths of Arab-inhabited lands were under Ottoman rule.

Influence of other languages on Arabic

The most important sources of borrowings into (pre-Islamic) Arabic are from the related (Semitic) languages Aramaic,[54] which used to be the principal, international language of communication throughout the ancient Near and Middle East, Ethiopic, and to a lesser degree Hebrew (mainly religious concepts). In addition, many cultural, religious and political terms have entered Arabic from Iranian languages, notably Middle Persian, Parthian, and (Classical) Persian,[55] and Hellenistic Greek (kīmiyāʼ has as origin the Greek khymia, meaning in that language the melting of metals; see Roger Dachez, Histoire de la Médecine de l'Antiquité au XXe siècle, Tallandier, 2008, p. 251), alembic (distiller) from ambix (cup), almanac (climate) from almenichiakon (calendar). (For the origin of the last three borrowed words, see Alfred-Louis de Prémare, Foundations of Islam, Seuil, L'Univers Historique, 2002.) Some Arabic borrowings from Semitic or Persian languages are, as presented in De Prémare's above-cited book:

- madīnah/medina (مدينة, city or city square), a word of Aramaic or Hebrew origin מדינה (in which it means "a state");

- jazīrah (جزيرة), as in the well-known form الجزيرة "Al-Jazeera," means "island" and has its origin in the Syriac ܓܙܝܪܗ gazīra.

- lāzaward (لازورد) is taken from Persian لاژورد lājvard, the name of a blue stone, lapis lazuli. This word was borrowed in several European languages to mean (light) blue – azure in English, azur in French and azul in Portuguese and Spanish.

Arabic alphabet and nationalism

There have been many instances of national movements to convert Arabic script into Latin script or to Romanize the language. Currently, the only language derived from Classical Arabic to use Latin script is Maltese.

Lebanon

The Beirut newspaper La Syrie pushed for the change from Arabic script to Latin letters in 1922. The major head of this movement was Louis Massignon, a French Orientalist, who brought his concern before the Arabic Language Academy in Damascus in 1928. Massignon's attempt at Romanization failed as the Academy and population viewed the proposal as an attempt from the Western world to take over their country. Sa'id Afghani, a member of the Academy, mentioned that the movement to Romanize the script was a Zionist plan to dominate Lebanon.[56][57]

Egypt

After the period of colonialism in Egypt, Egyptians were looking for a way to reclaim and re-emphasize Egyptian culture. As a result, some Egyptians pushed for an Egyptianization of the Arabic language in which the formal Arabic and the colloquial Arabic would be combined into one language and the Latin alphabet would be used.[56][57] There was also the idea of finding a way to use Hieroglyphics instead of the Latin alphabet, but this was seen as too complicated to use.[56][57] A scholar, Salama Musa agreed with the idea of applying a Latin alphabet to Arabic, as he believed that would allow Egypt to have a closer relationship with the West. He also believed that Latin script was key to the success of Egypt as it would allow for more advances in science and technology. This change in alphabet, he believed, would solve the problems inherent with Arabic, such as a lack of written vowels and difficulties writing foreign words that made it difficult for non-native speakers to learn.[56][57] Ahmad Lutfi As Sayid and Muhammad Azmi, two Egyptian intellectuals, agreed with Musa and supported the push for Romanization.[56][58] The idea that Romanization was necessary for modernization and growth in Egypt continued with Abd Al-Aziz Fahmi in 1944. He was the chairman for the Writing and Grammar Committee for the Arabic Language Academy of Cairo.[56][58] However, this effort failed as the Egyptian people felt a strong cultural tie to the Arabic alphabet.[56][58] In particular, the older Egyptian generations believed that the Arabic alphabet had strong connections to Arab values and history, due to the long history of the Arabic alphabet (Shrivtiel, 189) in Muslim societies.

The language of the Quran and its influence on poetry

The Quran introduced a new way of writing to the world. People began studying and applying the unique styles they learned from the Quran to not only their own writing, but also their culture. Writers studied the unique structure and format of the Quran in order to identify and apply the figurative devices and their impact on the reader.

Quran's figurative devices

The Quran inspired musicality in poetry through the internal rhythm of the verses. The arrangement of words, how certain sounds create harmony, and the agreement of rhymes create the sense of rhythm within each verse. At times, the chapters of the Quran only have the rhythm in common.[59]

The repetition in the Quran introduced the true power and impact repetition can have in poetry. The repetition of certain words and phrases made them appear more firm and explicit in the Quran. The Quran uses constant metaphors of blindness and deafness to imply unbelief. Metaphors were not a new concept to poetry, however the strength of extended metaphors was. The explicit imagery in the Quran inspired many poets to include and focus on the feature in their own work. The poet ibn al-Mu'tazz wrote a book regarding the figures of speech inspired by his study of the Quran. Poets such as badr Shakir al sayyab expresses his political opinion in his work through imagery inspired by the forms of more harsher imagery used in the Quran.[60] The Quran uses figurative devices in order to express the meaning in the most beautiful form possible. The study of the pauses in the Quran as well as other rhetoric allow it to be approached in a multiple ways.[61]

Structure

Although the Quran is known for its fluency and harmony, the structure can be best described as not always being inherently chronological, but can also flow thematically instead(the chapters in the Quran have segments that flow in chronological order, however segments can transition into other segments not related in chronology, but could be related in topic). The suras, also known as chapters of the Quran, are not placed in chronological order. The only constant in their structure is that the longest are placed first and shorter ones follow. The topics discussed in the chapters can also have no direct relation to each other (as seen in many suras) and can share in their sense of rhyme. The Quran introduces to poetry the idea of abandoning order and scattering narratives throughout the text. Harmony is also present in the sound of the Quran. The elongations and accents present in the Quran create a harmonious flow within the writing. Unique sound of the Quran recited, due to the accents, create a deeper level of understanding through a deeper emotional connection.[60]

The Quran is written in a language that is simple and understandable by people. The simplicity of the writing inspired later poets to write in a more clear and clear-cut style.[60] The words of the Quran, although unchanged, are to this day understandable and frequently used in both formal and informal Arabic. The simplicity of the language makes memorizing and reciting the Quran a slightly easier task.

Culture and the Quran

The writer al-Khattabi explains how culture is a required element to create a sense of art in work as well as understand it. He believes that the fluency and harmony which the Quran possess are not the only elements that make it beautiful and create a bond between the reader and the text. While a lot of poetry was deemed comparable to the Quran in that it is equal to or better than the composition of the Quran, a debate rose that such statements are not possible because humans are incapable of composing work comparable to the Quran.[61] Because the structure of the Quran made it difficult for a clear timeline to be seen, Hadith were the main source of chronological order. The Hadith were passed down from generation to generation and this tradition became a large resource for understanding the context. Poetry after the Quran began possessing this element of tradition by including ambiguity and background information to be required to understand the meaning.[59]

After the Quran came down to the people, the tradition of memorizing the verses became present. It is believed that the greater the amount of the Quran memorized, the greater the faith. As technology improved over time, hearing recitations of the Quran became more available as well as more tools to help memorize the verses. The tradition of Love Poetry served as a symbolic representation of a Muslim's desire for a closer contact with their Lord.

While the influence of the Quran on Arabic poetry is explained and defended by numerous writers, some writers such as Al-Baqillani believe that poetry and the Quran are in no conceivable way related due to the uniqueness of the Quran. Poetry's imperfections prove his points that they cannot be compared with the fluency the Quran holds.

Arabic and Islam

Classical Arabic is the language of poetry and literature (including news); it is also mainly the language of the Quran. Classical Arabic is closely associated with the religion of Islam because the Quran was written in it. Most of the world's Muslims do not speak Classical Arabic as their native language, but many can read the Quranic script and recite the Quran. Among non-Arab Muslims, translations of the Quran are most often accompanied by the original text. At present, Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is also used in modernized versions of literary forms of the Quran.

Some Muslims present a monogenesis of languages and claim that the Arabic language was the language revealed by God for the benefit of mankind and the original language as a prototype system of symbolic communication, based upon its system of triconsonantal roots, spoken by man from which all other languages were derived, having first been corrupted.[62] Judaism has a similar account with the Tower of Babel.

Dialects and descendants

Colloquial Arabic is a collective term for the spoken dialects of Arabic used throughout the Arab world, which differ radically from the literary language. The main dialectal division is between the varieties within and outside of the Arabian peninsula, followed by that between sedentary varieties and the much more conservative Bedouin varieties. All the varieties outside of the Arabian peninsula (which include the large majority of speakers) have many features in common with each other that are not found in Classical Arabic. This has led researchers to postulate the existence of a prestige koine dialect in the one or two centuries immediately following the Arab conquest, whose features eventually spread to all newly conquered areas. (These features are present to varying degrees inside the Arabian peninsula. Generally, the Arabian peninsula varieties have much more diversity than the non-peninsula varieties, but these have been understudied.)

Within the non-peninsula varieties, the largest difference is between the non-Egyptian North African dialects (especially Moroccan Arabic) and the others. Moroccan Arabic in particular is hardly comprehensible to Arabic speakers east of Libya (although the converse is not true, in part due to the popularity of Egyptian films and other media).

One factor in the differentiation of the dialects is influence from the languages previously spoken in the areas, which have typically provided a significant number of new words and have sometimes also influenced pronunciation or word order; however, a much more significant factor for most dialects is, as among Romance languages, retention (or change of meaning) of different classical forms. Thus Iraqi aku, Levantine fīh and North African kayən all mean 'there is', and all come from Classical Arabic forms (yakūn, fīhi, kā'in respectively), but now sound very different.

Examples

Transcription is a broad IPA transcription, so minor differences were ignored for easier comparison. Also, the pronunciation of Modern Standard Arabic differs significantly from region to region.

| Variety | I love reading a lot | When I went to the library | I didn't find this old book | I wanted to read a book about the history of women in France |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literary Arabic in Arabic script (common spelling) |

أحب القراءة كثيرا | عندما ذهبت إلى المكتبة | لم أجد هذا الكتاب القديم | كنت أريد أن أقرأ كتابا عن تاريخ المرأة في فرنسا |

| Literary Arabic in Arabic script (with all vowels) |

أُحِبُّ ٱلْقِرَاءَةَ كَثِيرًا | عِنْدَمَا ذَهَبْتُ إِلَى ٱلْمَكْتَبَةِ | لَمْ أَجِد هٰذَا ٱلْكِتَابَ ٱلْقَدِيمَ | كُنْتُ أُرِيدُ أَنْ أَقْرَأَ كِتَابًا عَنْ تَارِيخِ ٱلْمَرْأَةِ فِي فَرَنْسَا |

| Classical Arabic (liturgical or poetic only) |

ʔuħibːu‿lqirˤaːʔata kaθiːrˤaː | ʕĩndamaː ðahabᵊtu ʔila‿lmaktabah | lam ʔaɟidᵊ haːða‿lkitaːba‿lqadiːm | kũntu ʔuriːdu ʔan ʔaqᵊrˤaʔa kitaːban ʕan taːriːχi‿lmarˤʔati fiː farˤãnsaː |

| Modern Standard Arabic | ʔuħibːu‿lqiraːʔa kaθiːran | ʕindamaː ðahabt ʔila‿lmaktaba | lam ʔad͡ʒid haːða‿lkitaːba‿lqadiːm | kunt ʔuriːd ʔan ʔaqraʔ kitaːban ʕan taːriːχi‿lmarʔa fiː faransaː |

| Yemeni Arabic (Sanaa) | ana bajn aħibː ilgiraːji(h) gawi | law ma sirt saˈla‿lmaktabih | ma lige:tʃ ðajji‿lkitaːb ilgadiːm | kunt aʃti ʔagra kitaːb ʕan taːriːx ilmari(h) wastˤ faraːnsa |

| Jordanian Arabic (Amman) | ana baħib ligraːje kθiːr | lamːa ruħt ʕalmaktabe | ma lageːtʃ haliktaːb ilgadiːm | kaːn bidːi ʔaqra ktaːb ʕan taːriːx ilmara fi faransa |

| Gulf Arabic (Kuwait) | aːna waːjid aħibː aɡra | lamːan riħt ilmaktaba | maː liɡeːt halkitaːb ilgadiːm | kint abi‿(j)aɡra kitaːb ʕan taːriːx ilħariːm‿(i)bfaransa |

| Gələt Mesopotamian (Baghdad) | aːni‿(j)aħub luqraːja kulːiʃ | lamːan riħit lilmaktabˤɛː | maː liɡeːt haːða liktaːb ilgadiːm | ridit aqra ktaːb ʕan taːriːx inːiswaːn‿(u)bfransɛː |

| Hejazi Arabic (Medina) | ana marːa ʔaħubː alɡiraːja | lamːa ruħt almaktaba | ma liɡiːt haːda lkitaːb alɡadiːm | kunt abɣa ʔaɡra kitaːb ʕan taːriːx alħariːm fi faransa |

| Western Syrian Arabic (Damascus) | ana ktiːr bħəb ləʔraːje | lamːa rəħt ʕalmaktabe | ma laʔeːt haləktaːb əlʔadiːm | kaːn badːi ʔra ktaːb ʕan taːriːx əlmara bfraːnsa |

| Lebanese Arabic (Beirut?) | ana ktiːr bħib liʔreːji | lamːa riħit ʕalmaktabi | ma lʔeːt halikteːb liʔdiːm | keːn badːi ʔra kteːb ʕan teːriːx ilmara bfraːnsa |

| Urban Palestinian (Jerusalem) | ana baħib liʔraːje ktiːr | lamːa ruħt ʕalmaktabe | ma laʔeːtʃ haliktaːb ilʔadiːm | kaːn bidːi ʔaʔra ktaːb ʕan taːriːx ilmara fi faransa |

| Rural Palestinian (West Bank) | ana baħib likraːje kθiːr | lamːa ruħt ʕalmatʃtabe | ma lakeːtʃ halitʃtaːb ilkadiːm | kaːn bidːi ʔakra tʃtaːb ʕan taːriːx ilmara fi faransa |

| Egyptian (metropolitan) | ana baħebː elʔeraːja ʔawi | lamːa roħt elmakˈtaba | malʔetʃ elketaːb elʔadim da | ana kont(e)‿ʕawz‿aʔra ktab ʕan tariːx esːetˈtat fe faransa |

| Libyan Arabic (Tripoli?) | ana nħəb il-ɡraːja halba | lamma mʃeːt lil-maktba | malɡeːtiʃ ha-li-ktaːb lə-ɡdiːm | kunt nibi naɡra ktaːb ʔleː tariːx ə-nsawiːn fi fraːnsa |

| Tunisian (Tunis) | nħib liqraːja barʃa | waqtilli mʃiːt lilmaktba | mal-qiːtʃ ha-likteːb liqdiːm | kʊnt nħib naqra kteːb ʕla terix limra fi fraːnsa |

| Algerian (Algiers?) | āna nħəbb nəqṛa bezzaf | ki ruħt l-əl-măktaba | ma-lqīt-ʃ hād lə-ktāb lə-qdīm | kŭnt ħābb nəqṛa ktāb ʕla tārīx lə-mṛa fi fṛānsa |

| Moroccan (Rabat?) | ana ʕziz ʕlija bzzaf nqra | melli mʃit l-lmaktaba | ma-lqiːt-ʃ had l-ktab l-qdim | kent baɣi nqra ktab ʕla tarix l-mra f-fransa |

| Maltese (Valletta) (in Maltese orthography) |

Inħobb naqra ħafna. | Meta mort il-librerija | Ma sibtx dan il-ktieb qadim. | Ridt naqra ktieb dwar l-istorja tal-mara fi Franza. |

Koiné

According to Charles A. Ferguson,[63] the following are some of the characteristic features of the koiné that underlies all the modern dialects outside the Arabian peninsula. Although many other features are common to most or all of these varieties, Ferguson believes that these features in particular are unlikely to have evolved independently more than once or twice and together suggest the existence of the koine:

- Loss of the dual number except on nouns, with consistent plural agreement (cf. feminine singular agreement in plural inanimates).

- Change of a to i in many affixes (e.g., non-past-tense prefixes ti- yi- ni-; wi- 'and'; il- 'the'; feminine -it in the construct state).

- Loss of third-weak verbs ending in w (which merge with verbs ending in y).

- Reformation of geminate verbs, e.g., ḥalaltu 'I untied' → ḥalēt(u).

- Conversion of separate words lī 'to me', laka 'to you', etc. into indirect-object clitic suffixes.

- Certain changes in the cardinal number system, e.g., khamsat ayyām 'five days' → kham(a)s tiyyām, where certain words have a special plural with prefixed t.

- Loss of the feminine elative (comparative).

- Adjective plurals of the form kibār 'big' → kubār.

- Change of nisba suffix -iyy > i.

- Certain lexical items, e.g., jāb 'bring' < jāʼa bi- 'come with'; shāf 'see'; ēsh 'what' (or similar) < ayyu shayʼ 'which thing'; illi (relative pronoun).

- Merger of /ɮˤ/ and /ðˤ/.

Dialect groups

- Egyptian Arabic is spoken by around 53 million people in Egypt (55 million worldwide).[64] It is one of the most understood varieties of Arabic, due in large part to the widespread distribution of Egyptian films and television shows throughout the Arabic-speaking world

- Levantine Arabic includes North Levantine Arabic, South Levantine Arabic and Cypriot Arabic. It is spoken by about 21 million people in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, Cyprus and Turkey.

- Lebanese Arabic is a variety of Levantine Arabic spoken primarily in Lebanon.

- Jordanian Arabic is a continuum of mutually intelligible varieties of Levantine Arabic spoken by the population of the Kingdom of Jordan.

- Palestinian Arabic is a name of several dialects of the subgroup of Levantine Arabic spoken by the Palestinians in Palestine, by Arab citizens of Israel and in most Palestinian populations around the world.

- Samaritan Arabic, spoken by only several hundred in the Nablus region

- Cypriot Maronite Arabic, spoken in Cyprus

- Maghrebi Arabic, also called "Darija" spoken by about 70 million people in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. It also forms the basis of Maltese via the extinct Sicilian Arabic dialect.[65] Maghrebi Arabic is very hard to understand for Arabic speakers from the Mashriq or Mesopotamia, the most comprehensible being Libyan Arabic and the most difficult Moroccan Arabic. The others such as Algerian Arabic can be considered in between the two in terms of difficulty.

- Libyan Arabic spoken in Libya and neighboring countries.

- Tunisian Arabic spoken in Tunisia and North-eastern Algeria

- Algerian Arabic spoken in Algeria

- Judeo-Algerian Arabic was spoken by Jews in Algeria until 1962

- Moroccan Arabic spoken in Morocco

- Hassaniya Arabic (3 million speakers), spoken in Mauritania, Western Sahara, some parts of the Azawad in northern Mali, southern Morocco and south-western Algeria.

- Andalusian Arabic, spoken in Spain until the 16th century.

- Siculo-Arabic (Sicilian Arabic), was spoken in Sicily and Malta between the end of the ninth century and the end of the twelfth century and eventually evolved into the Maltese language.

- Maltese, spoken on the island of Malta, is the only fully separate standardized language to have originated from an Arabic dialect (the extinct Siculo-Arabic dialect), with independent literary norms. Maltese has evolved independently of Literary Arabic and its varieties into a standardized language over the past 800 years in a gradual process of Latinisation.[66][67] Maltese is therefore considered an exceptional descendant of Arabic that has no diglossic relationship with Standard Arabic or Classical Arabic.[68] Maltese is also different from Arabic and other Semitic languages since its morphology has been deeply influenced by Romance languages, Italian and Sicilian.[69] It is also the only Semitic language written in the Latin script. In terms of basic everyday language, speakers of Maltese are reported to be able to understand less than a third of what is said to them in Tunisian Arabic,[70] which is related to Siculo-Arabic,[65] whereas speakers of Tunisian are able to understand about 40% of what is said to them in Maltese.[71] This asymmetric intelligibility is considerably lower than the mutual intelligibility found between Maghrebi Arabic dialects.[72] Maltese has its own dialects, with urban varieties of Maltese being closer to Standard Maltese than rural varieties.[73]

- Mesopotamian Arabic, spoken by about 32 million people in Iraq (where it is called "Aamiyah"), eastern Syria and southwestern Iran (Khuzestan).

- Baghdad Arabic is the Arabic dialect spoken in Baghdad, the capital of Iraq. It is a subvariety of Mesopotamian Arabic.

- Kuwaiti Arabic is a Gulf Arabic dialect spoken in Kuwait.

- Khuzestani Arabic spoken in the Iranian province of Khuzestan.

- Khorasani Arabic spoken in the Iranian province of Khorasan.

- Sudanese Arabic is spoken by 17 million people in Sudan and some parts of southern Egypt. Sudanese Arabic is quite distinct from the dialect of its neighbor to the north; rather, the Sudanese have a dialect similar to the Hejazi dialect.

- Juba Arabic spoken in South Sudan and southern Sudan

- Gulf Arabic, spoken by around four million people, predominantly in Kuwait, Bahrain, some parts of Oman, eastern Saudi Arabia coastal areas and some parts of UAE and Qatar. Also spoken in Iran's Bushehr and Hormozgan provinces. Although Gulf Arabic is spoken in Qatar, most Qatari citizens speak Najdi Arabic (Bedawi).

- Omani Arabic, distinct from the Gulf Arabic of eastern Arabia and Bahrain, spoken in Central Oman. With recent oil wealth and mobility has spread over other parts of the Sultanate.

- Hadhrami Arabic, Spoken by around 8 million people, predominantly in Hadhramaut, and in parts of the Arabian Peninsula, South and Southeast Asia, and East Africa by Hadhrami descendants.

- Yemeni Arabic spoken in Yemen, and southern Saudi Arabia by 15 million people. Similar to Gulf Arabic.

- Najdi Arabic, spoken by around 10 million people, mainly spoken in Najd, central and northern Saudi Arabia. Most Qatari citizens speak Najdi Arabic (Bedawi).

- Hejazi Arabic (6 million speakers), spoken in Hejaz, western Saudi Arabia

- Saharan Arabic spoken in some parts of Algeria, Niger and Mali

- Baharna Arabic (600,000 speakers), spoken by Bahrani Shiʻah in Bahrain and Qatif, the dialect exhibits many big differences from Gulf Arabic. It is also spoken to a lesser extent in Oman.

- Judeo-Arabic dialects – these are the dialects spoken by the Jews that had lived or continue to live in the Arab World. As Jewish migration to Israel took hold, the language did not thrive and is now considered endangered. So-called Qәltu Arabic.

- Chadian Arabic, spoken in Chad, Sudan, some parts of South Sudan, Central African Republic, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon

- Central Asian Arabic, spoken in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan, is highly endangered

- Shirvani Arabic, spoken in Azerbaijan and Dagestan until the 1930s, now extinct.

Phonology

History

Of the 29 Proto-Semitic consonants, only one has been lost: */ʃ/, which merged with /s/, while /ɬ/ became /ʃ/ (see Semitic languages).[74] Various other consonants have changed their sound too, but have remained distinct. An original */p/ lenited to /f/, and */ɡ/ – consistently attested in pre-Islamic Greek transcription of Arabic languages[75] – became palatalized to /ɡʲ/ or /ɟ/ by the time of the Quran and /d͡ʒ/, /ɡ/, /ʒ/ or /ɟ/ after early Muslim conquests and in MSA (see Arabic phonology#Local variations for more detail).[76] An original voiceless alveolar lateral fricative */ɬ/ became /ʃ/.[77] Its emphatic counterpart /ɬˠ~ɮˤ/ was considered by Arabs to be the most unusual sound in Arabic (Hence the Classical Arabic's appellation لُغَةُ ٱلضَّادِ lughat al-ḍād or "language of the ḍād"); for most modern dialects, it has become an emphatic stop /dˤ/ with loss of the laterality[77] or with complete loss of any pharyngealization or velarization, /d/. (The classical ḍād pronunciation of pharyngealization /ɮˤ/ still occurs in the Mehri language, and the similar sound without velarization, /ɮ/, exists in other Modern South Arabian languages.)

Other changes may also have happened. Classical Arabic pronunciation is not thoroughly recorded and different reconstructions of the sound system of Proto-Semitic propose different phonetic values. One example is the emphatic consonants, which are pharyngealized in modern pronunciations but may have been velarized in the eighth century and glottalized in Proto-Semitic.[77]

Reduction of /j/ and /w/ between vowels occurs in a number of circumstances and is responsible for much of the complexity of third-weak ("defective") verbs. Early Akkadian transcriptions of Arabic names shows that this reduction had not yet occurred as of the early part of the 1st millennium BC.

The Classical Arabic language as recorded was a poetic koine that reflected a consciously archaizing dialect, chosen based on the tribes of the western part of the Arabian Peninsula, who spoke the most conservative variants of Arabic. Even at the time of Muhammed and before, other dialects existed with many more changes, including the loss of most glottal stops, the loss of case endings, the reduction of the diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/ into monophthongs /eː, oː/, etc. Most of these changes are present in most or all modern varieties of Arabic.

An interesting feature of the writing system of the Quran (and hence of Classical Arabic) is that it contains certain features of Muhammad's native dialect of Mecca, corrected through diacritics into the forms of standard Classical Arabic. Among these features visible under the corrections are the loss of the glottal stop and a differing development of the reduction of certain final sequences containing /j/: Evidently, final /-awa/ became /aː/ as in the Classical language, but final /-aja/ became a different sound, possibly /eː/ (rather than again /aː/ in the Classical language). This is the apparent source of the alif maqṣūrah 'restricted alif' where a final /-aja/ is reconstructed: a letter that would normally indicate /j/ or some similar high-vowel sound, but is taken in this context to be a logical variant of alif and represent the sound /aː/.

Although Classical Arabic was a unitary language and is now used in Quran, its pronunciation varies somewhat from country to country and from region to region within a country. It is influenced by colloquial dialects.

Literary Arabic

The "colloquial" spoken dialects of Arabic are learned at home and constitute the native languages of Arabic speakers. "Formal" Literary Arabic (usually specifically Modern Standard Arabic) is learned at school; although many speakers have a native-like command of the language, it is technically not the native language of any speakers. Both varieties can be both written and spoken, although the colloquial varieties are rarely written down and the formal variety is spoken mostly in formal circumstances, e.g., in radio and TV broadcasts, formal lectures, parliamentary discussions and to some extent between speakers of different colloquial dialects. Even when the literary language is spoken, however, it is normally only spoken in its pure form when reading a prepared text out loud and communication between speakers of different colloquial dialects. When speaking extemporaneously (i.e. making up the language on the spot, as in a normal discussion among people), speakers tend to deviate somewhat from the strict literary language in the direction of the colloquial varieties. In fact, there is a continuous range of "in-between" spoken varieties: from nearly pure Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), to a form that still uses MSA grammar and vocabulary but with significant colloquial influence, to a form of the colloquial language that imports a number of words and grammatical constructions in MSA, to a form that is close to pure colloquial but with the "rough edges" (the most noticeably "vulgar" or non-Classical aspects) smoothed out, to pure colloquial. The particular variant (or register) used depends on the social class and education level of the speakers involved and the level of formality of the speech situation. Often it will vary within a single encounter, e.g., moving from nearly pure MSA to a more mixed language in the process of a radio interview, as the interviewee becomes more comfortable with the interviewer. This type of variation is characteristic of the diglossia that exists throughout the Arabic-speaking world.

Although Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is a unitary language, its pronunciation varies somewhat from country to country and from region to region within a country. The variation in individual "accents" of MSA speakers tends to mirror corresponding variations in the colloquial speech of the speakers in question, but with the distinguishing characteristics moderated somewhat. It is important in descriptions of "Arabic" phonology to distinguish between pronunciation of a given colloquial (spoken) dialect and the pronunciation of MSA by these same speakers. Although they are related, they are not the same. For example, the phoneme that derives from Classical Arabic /ɟ/ has many different pronunciations in the modern spoken varieties, e.g., [d͡ʒ ~ ʒ ~ j ~ ɡʲ ~ ɡ] including the proposed original [ɟ]. Speakers whose native variety has either [d͡ʒ] or [ʒ] will use the same pronunciation when speaking MSA. Even speakers from Cairo, whose native Egyptian Arabic has [ɡ], normally use [ɡ] when speaking MSA. The [j] of Persian Gulf speakers is the only variant pronunciation which isn't found in MSA; [d͡ʒ~ʒ] is used instead, but may use [j] in MSA for comfortable pronunciation. Another reason of different pronunciations is influence of colloquial dialects. The differentiation of pronunciation of colloquial dialects is the influence from other languages previously spoken and some still presently spoken in the regions, such as Coptic in Egypt, Berber, Punic, or Phoenician in North Africa, Himyaritic, Modern South Arabian, and Old South Arabian in Yemen and Oman, and Aramaic and Canaanite languages (including Phoenician) in the Levant and Mesopotamia.

Another example: Many colloquial varieties are known for a type of vowel harmony in which the presence of an "emphatic consonant" triggers backed allophones of nearby vowels (especially of the low vowels /aː/, which are backed to [ɑ(ː)] in these circumstances and very often fronted to [æ(ː)] in all other circumstances). In many spoken varieties, the backed or "emphatic" vowel allophones spread a fair distance in both directions from the triggering consonant; in some varieties (most notably Egyptian Arabic), the "emphatic" allophones spread throughout the entire word, usually including prefixes and suffixes, even at a distance of several syllables from the triggering consonant. Speakers of colloquial varieties with this vowel harmony tend to introduce it into their MSA pronunciation as well, but usually with a lesser degree of spreading than in the colloquial varieties. (For example, speakers of colloquial varieties with extremely long-distance harmony may allow a moderate, but not extreme, amount of spreading of the harmonic allophones in their MSA speech, while speakers of colloquial varieties with moderate-distance harmony may only harmonize immediately adjacent vowels in MSA.)

Vowels

Modern Standard Arabic has six pure vowels (while most modern dialects have eight pure vowels which includes the long vowels /eː oː/), with short /a i u/ and corresponding long vowels /aː iː uː/. There are also two diphthongs: /aj/ and /aw/.

The pronunciation of the vowels differs from speaker to speaker, in a way that tends to reflect the pronunciation of the corresponding colloquial variety. Nonetheless, there are some common trends. Most noticeable is the differing pronunciation of /a/ and /aː/, which tend towards fronted [æ(ː)], [a(ː)] or [ɛ(ː)] in most situations, but a back [ɑ(ː)] in the neighborhood of emphatic consonants. Some accents and dialects, such as those of the Hejaz region, have an open [a(ː)] or a central [ä(ː)] in all situations. The vowel /a/ varies towards [ə(ː)] too. Listen to the final vowel in the recording of al-ʻarabiyyah at the beginning of this article, for example. The point is, Arabic has only three short vowel phonemes, so those phonemes can have a very wide range of allophones. The vowels /u/ and /ɪ/ are often affected somewhat in emphatic neighborhoods as well, with generally more back or centralized allophones, but the differences are less great than for the low vowels. The pronunciation of short /u/ and /i/ tends towards [ʊ~o] and [i~e~ɨ], respectively, in many dialects.

The definition of both "emphatic" and "neighborhood" vary in ways that reflect (to some extent) corresponding variations in the spoken dialects. Generally, the consonants triggering "emphatic" allophones are the pharyngealized consonants /tˤ dˤ sˤ ðˤ/; /q/; and /r/, if not followed immediately by /i(ː)/. Frequently, the velar fricatives /x ɣ/ also trigger emphatic allophones; occasionally also the pharyngeal consonants /ʕ ħ/ (the former more than the latter). Many dialects have multiple emphatic allophones of each vowel, depending on the particular nearby consonants. In most MSA accents, emphatic coloring of vowels is limited to vowels immediately adjacent to a triggering consonant, although in some it spreads a bit farther: e.g., وقت waqt [wɑqt] 'time'; وطن waṭan [wɑtˤɑn] 'homeland'; وسط المدينة wasṭ al-madīnah [wæstˤ ɑl mædiːnɐ] 'downtown' (sometimes [wɑstˤ ɑl mædiːnæ] or similar).

In a non-emphatic environment, the vowel /a/ in the diphthong /aj/ tends to be fronted even more than elsewhere, often pronounced [æj] or [ɛj]: hence سيف sayf [sajf ~ sæjf ~ sɛjf] 'sword' but صيف ṣayf [sˤɑjf] 'summer'. However, in accents with no emphatic allophones of /a/ (e.g., in the Hejaz), the pronunciation [aj] or [äj] occurs in all situations.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | t | tˤ | k | q | ʔ | ||||

| voiced | b | d | dˤ | d͡ʒ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | x ~ χ | ħ | ||

| voiced | ð | z | ðˤ | ɣ ~ ʁ | ʕ | ɦ | ||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

| Approximant | l | (ɫ) | j | w | ||||||

The phoneme /d͡ʒ/ is represented by the Arabic letter jīm (ج) and has many standard pronunciations. [d͡ʒ] is characteristic of north Algeria, Iraq, and most of the Arabian peninsula but with an allophonic [ʒ] in some positions; [ʒ] occurs in most of the Levant and most of North Africa; and [ɡ] is used in most of Egypt and some regions in Yemen and Oman. Generally this corresponds with the pronunciation in the colloquial dialects.[78] In some regions in Sudan and Yemen, as well as in some Sudanese and Yemeni dialects, it may be either [ɡʲ] or [ɟ], representing the original pronunciation of Classical Arabic. Foreign words containing /ɡ/ may be transcribed with ج, غ, ك, ق, گ, ݣ or ڨ, mainly depending on the regional spoken variety of Arabic or the commonly diacriticized Arabic letter. In northern Egypt, where the Arabic letter jīm (ج) is normally pronounced [ɡ], a separate phoneme /ʒ/, which may be transcribed with چ, occurs in a small number of mostly non-Arabic loanwords, e.g., /ʒakitta/ 'jacket'.

/θ/ (ث) can be pronounced as [s]. In some places of Maghreb it can be also pronounced as [t͡s].

/x/ and /ɣ/ (خ, غ) are velar, post-velar, or uvular.[79]

In many varieties, /ħ, ʕ/ (ح, ع) are epiglottal [ʜ, ʢ] in Western Asia.

/l/ is pronounced as velarized [ɫ] in الله /ʔallaːh/, the name of God, q.e. Allah, when the word follows a, ā, u or ū (after i or ī it is unvelarized: بسم الله bismi l–lāh /bismillaːh/). Some speakers velarize other occurrences of /l/ in MSA, in imitation of their spoken dialects.

The emphatic consonant /dˤ/ was actually pronounced [ɮˤ], or possibly [d͡ɮˤ][80]—either way, a highly unusual sound. The medieval Arabs actually termed their language lughat al-ḍād 'the language of the Ḍād' (the name of the letter used for this sound), since they thought the sound was unique to their language. (In fact, it also exists in a few other minority Semitic languages, e.g., Mehri.)

Arabic has consonants traditionally termed "emphatic" /tˤ, dˤ, sˤ, ðˤ/ (ط, ض, ص, ظ), which exhibit simultaneous pharyngealization [tˤ, dˤ, sˤ, ðˤ] as well as varying degrees of velarization [tˠ, dˠ, sˠ, ðˠ] (depending on the region), so they may be written with the "Velarized or pharyngealized" diacritic ( ̴) as: /t̴, d̴, s̴, ð̴/. This simultaneous articulation is described as "Retracted Tongue Root" by phonologists.[81] In some transcription systems, emphasis is shown by capitalizing the letter, for example, /dˤ/ is written ⟨D⟩; in others the letter is underlined or has a dot below it, for example, ⟨ḍ⟩.

Vowels and consonants can be phonologically short or long. Long (geminate) consonants are normally written doubled in Latin transcription (i.e. bb, dd, etc.), reflecting the presence of the Arabic diacritic mark shaddah, which indicates doubled consonants. In actual pronunciation, doubled consonants are held twice as long as short consonants. This consonant lengthening is phonemically contrastive: قبل qabila 'he accepted' vs. قبّل qabbala 'he kissed'.

Syllable structure

Arabic has two kinds of syllables: open syllables (CV) and (CVV)—and closed syllables (CVC), (CVVC) and (CVCC). The syllable types with two morae (units of time), i.e. CVC and CVV, are termed heavy syllables, while those with three morae, i.e. CVVC and CVCC, are superheavy syllables. Superheavy syllables in Classical Arabic occur in only two places: at the end of the sentence (due to pausal pronunciation) and in words such as حارّ ḥārr 'hot', مادّة māddah 'stuff, substance', تحاجوا taḥājjū 'they disputed with each other', where a long ā occurs before two identical consonants (a former short vowel between the consonants has been lost). (In less formal pronunciations of Modern Standard Arabic, superheavy syllables are common at the end of words or before clitic suffixes such as -nā 'us, our', due to the deletion of final short vowels.)

In surface pronunciation, every vowel must be preceded by a consonant (which may include the glottal stop [ʔ]). There are no cases of hiatus within a word (where two vowels occur next to each other, without an intervening consonant). Some words do have an underlying vowel at the beginning, such as the definite article al- or words such as اشترا ishtarā 'he bought', اجتماع ijtimāʻ 'meeting'. When actually pronounced, one of three things happens:

- If the word occurs after another word ending in a consonant, there is a smooth transition from final consonant to initial vowel, e.g., الاجتماع al-ijtimāʻ 'meeting' /alid͡ʒtimaːʕ/.

- If the word occurs after another word ending in a vowel, the initial vowel of the word is elided, e.g., بيت المدير baytu (a)l-mudīr 'house of the director' /bajtulmudiːr/.

- If the word occurs at the beginning of an utterance, a glottal stop [ʔ] is added onto the beginning, e.g., البيت هو al-baytu huwa ... 'The house is ...' /ʔalbajtuhuwa ... /.

Stress

Word stress is not phonemically contrastive in Standard Arabic. It bears a strong relationship to vowel length. The basic rules for Modern Standard Arabic are:

- A final vowel, long or short, may not be stressed.

- Only one of the last three syllables may be stressed.

- Given this restriction, the last heavy syllable (containing a long vowel or ending in a consonant) is stressed, if it is not the final syllable.

- If the final syllable is super heavy and closed (of the form CVVC or CVCC) it receives stress.

- If no syllable is heavy or super heavy, the first possible syllable (i.e. third from end) is stressed.

- As a special exception, in Form VII and VIII verb forms stress may not be on the first syllable, despite the above rules: Hence inkatab(a) 'he subscribed' (whether or not the final short vowel is pronounced), yankatib(u) 'he subscribes' (whether or not the final short vowel is pronounced), yankatib 'he should subscribe (juss.)'. Likewise Form VIII ishtarā 'he bought', yashtarī 'he buys'.

Examples:kitāb(un) 'book', kā-ti-b(un) 'writer', mak-ta-b(un) 'desk', ma-kā-ti-b(u) 'desks', mak-ta-ba-tun 'library' (but mak-ta-ba(-tun) 'library' in short pronunciation), ka-ta-bū (Modern Standard Arabic) 'they wrote' = ka-ta-bu (dialect), ka-ta-bū-h(u) (Modern Standard Arabic) 'they wrote it' = ka-ta-bū (dialect), ka-ta-ba-tā (Modern Standard Arabic) 'they (dual, fem) wrote', ka-tab-tu (Modern Standard Arabic) 'I wrote' = ka-tabt (short form or dialect). Doubled consonants count as two consonants: ma-jal-la-(tan) 'magazine', ma-ḥall(-un) "place".

These rules may result in differently stressed syllables when final case endings are pronounced, vs. the normal situation where they are not pronounced, as in the above example of mak-ta-ba-tun 'library' in full pronunciation, but mak-ta-ba(-tun) 'library' in short pronunciation.

The restriction on final long vowels does not apply to the spoken dialects, where original final long vowels have been shortened and secondary final long vowels have arisen from loss of original final -hu/hi.

Some dialects have different stress rules. In the Cairo (Egyptian Arabic) dialect a heavy syllable may not carry stress more than two syllables from the end of a word, hence mad-ra-sah 'school', qā-hi-rah 'Cairo'. This also affects the way that Modern Standard Arabic is pronounced in Egypt. In the Arabic of Sanaa, stress is often retracted: bay-tayn 'two houses', mā-sat-hum 'their table', ma-kā-tīb 'desks', zā-rat-ḥīn 'sometimes', mad-ra-sat-hum 'their school'. (In this dialect, only syllables with long vowels or diphthongs are considered heavy; in a two-syllable word, the final syllable can be stressed only if the preceding syllable is light; and in longer words, the final syllable cannot be stressed.)

Levels of pronunciation

The final short vowels (e.g., the case endings -a -i -u and mood endings -u -a) are often not pronounced in this language, despite forming part of the formal paradigm of nouns and verbs. The following levels of pronunciation exist:

Full pronunciation with pausa

This is the most formal level actually used in speech. All endings are pronounced as written, except at the end of an utterance, where the following changes occur:

- Final short vowels are not pronounced. (But possibly an exception is made for feminine plural -na and shortened vowels in the jussive/imperative of defective verbs, e.g., irmi! 'throw!'".)

- The entire indefinite noun endings -in and -un (with nunation) are left off. The ending -an is left off of nouns preceded by a tāʾ marbūṭah ة (i.e. the -t in the ending -at- that typically marks feminine nouns), but pronounced as -ā in other nouns (hence its writing in this fashion in the Arabic script).

- The tāʼ marbūṭah itself (typically of feminine nouns) is pronounced as h. (At least, this is the case in extremely formal pronunciation, e.g., some Quranic recitations. In practice, this h is usually omitted.)

Formal short pronunciation

This is a formal level of pronunciation sometimes seen. It is somewhat like pronouncing all words as if they were in pausal position (with influence from the colloquial varieties). The following changes occur:

- Most final short vowels are not pronounced. However, the following short vowels are pronounced:

- feminine plural -na

- shortened vowels in the jussive/imperative of defective verbs, e.g., irmi! 'throw!'

- second-person singular feminine past-tense -ti and likewise anti 'you (fem. sg.)'

- sometimes, first-person singular past-tense -tu

- sometimes, second-person masculine past-tense -ta and likewise anta 'you (masc. sg.)'

- final -a in certain short words, e.g., laysa 'is not', sawfa (future-tense marker)

- The nunation endings -an -in -un are not pronounced. However, they are pronounced in adverbial accusative formations, e.g., taqrīban تَقْرِيبًا 'almost, approximately', ʻādatan عَادَةً 'usually'.

- The tāʾ marbūṭah ending ة is unpronounced, except in construct state nouns, where it sounds as t (and in adverbial accusative constructions, e.g., ʻādatan عَادَةً 'usually', where the entire -tan is pronounced).

- The masculine singular nisbah ending -iyy is actually pronounced -ī and is unstressed (but plural and feminine singular forms, i.e. when followed by a suffix, still sound as -iyy-).

- Full endings (including case endings) occur when a clitic object or possessive suffix is added (e.g., -nā 'us/our').

Informal short pronunciation

This is the pronunciation used by speakers of Modern Standard Arabic in extemporaneous speech, i.e. when producing new sentences rather than simply reading a prepared text. It is similar to formal short pronunciation except that the rules for dropping final vowels apply even when a clitic suffix is added. Basically, short-vowel case and mood endings are never pronounced and certain other changes occur that echo the corresponding colloquial pronunciations. Specifically:

- All the rules for formal short pronunciation apply, except as follows.

- The past tense singular endings written formally as -tu -ta -ti are pronounced -t -t -ti. But masculine ʾanta is pronounced in full.

- Unlike in formal short pronunciation, the rules for dropping or modifying final endings are also applied when a clitic object or possessive suffix is added (e.g., -nā 'us/our'). If this produces a sequence of three consonants, then one of the following happens, depending on the speaker's native colloquial variety:

- A short vowel (e.g., -i- or -ǝ-) is consistently added, either between the second and third or the first and second consonants.

- Or, a short vowel is added only if an otherwise unpronounceable sequence occurs, typically due to a violation of the sonority hierarchy (e.g., -rtn- is pronounced as a three-consonant cluster, but -trn- needs to be broken up).

- Or, a short vowel is never added, but consonants like r l m n occurring between two other consonants will be pronounced as a syllabic consonant (as in the English words "butter bottle bottom button").

- When a doubled consonant occurs before another consonant (or finally), it is often shortened to a single consonant rather than a vowel added. (However, Moroccan Arabic never shortens doubled consonants or inserts short vowels to break up clusters, instead tolerating arbitrary-length series of arbitrary consonants and hence Moroccan Arabic speakers are likely to follow the same rules in their pronunciation of Modern Standard Arabic.)

- The clitic suffixes themselves tend also to be changed, in a way that avoids many possible occurrences of three-consonant clusters. In particular, -ka -ki -hu generally sound as -ak -ik -uh.

- Final long vowels are often shortened, merging with any short vowels that remain.

- Depending on the level of formality, the speaker's education level, etc., various grammatical changes may occur in ways that echo the colloquial variants:

- Any remaining case endings (e.g. masculine plural nominative -ūn vs. oblique -īn) will be leveled, with the oblique form used everywhere. (However, in words like ab 'father' and akh 'brother' with special long-vowel case endings in the construct state, the nominative is used everywhere, hence abū 'father of', akhū 'brother of'.)

- Feminine plural endings in verbs and clitic suffixes will often drop out, with the masculine plural endings used instead. If the speaker's native variety has feminine plural endings, they may be preserved, but will often be modified in the direction of the forms used in the speaker's native variety, e.g. -an instead of -na.

- Dual endings will often drop out except on nouns and then used only for emphasis (similar to their use in the colloquial varieties); elsewhere, the plural endings are used (or feminine singular, if appropriate).

Colloquial varieties

Vowels

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As mentioned above, many spoken dialects have a process of emphasis spreading, where the "emphasis" (pharyngealization) of emphatic consonants spreads forward and back through adjacent syllables, pharyngealizing all nearby consonants and triggering the back allophone [ɑ(ː)] in all nearby low vowels. The extent of emphasis spreading varies. For example, in Moroccan Arabic, it spreads as far as the first full vowel (i.e. sound derived from a long vowel or diphthong) on either side; in many Levantine dialects, it spreads indefinitely, but is blocked by any /j/ or /ʃ/; while in Egyptian Arabic, it usually spreads throughout the entire word, including prefixes and suffixes. In Moroccan Arabic, /i u/ also have emphatic allophones [e~ɛ] and [o~ɔ], respectively.

Unstressed short vowels, especially /i u/, are deleted in many contexts. Many sporadic examples of short vowel change have occurred (especially /a/→/i/ and interchange /i/↔/u/). Most Levantine dialects merge short /i u/ into /ə/ in most contexts (all except directly before a single final consonant). In Moroccan Arabic, on the other hand, short /u/ triggers labialization of nearby consonants (especially velar consonants and uvular consonants), and then short /a i u/ all merge into /ə/, which is deleted in many contexts. (The labialization plus /ə/ is sometimes interpreted as an underlying phoneme /ŭ/.) This essentially causes the wholesale loss of the short-long vowel distinction, with the original long vowels /aː iː uː/ remaining as half-long [aˑ iˑ uˑ], phonemically /a i u/, which are used to represent both short and long vowels in borrowings from Literary Arabic.

Most spoken dialects have monophthongized original /aj aw/ to /eː oː/ in most circumstances, including adjacent to emphatic consonants, while keeping them as the original diphthongs in others e.g. مَوْعِد /mawʕid/. In most of the Moroccan, Algerian and Tunisian (except Sahel and Southeastern) Arabic dialects, they have subsequently merged into original /iː uː/.

Consonants

In most dialects, there may be more or fewer phonemes than those listed in the chart above. For example, [g] is considered a native phoneme in most Arabic dialects except in Levantine dialects like Syrian or Lebanese where ج is pronounced [ʒ] and ق is pronounced [ʔ]. [d͡ʒ] or [ʒ] (ج) is considered a native phoneme in most dialects except in Egyptian and a number of Yemeni and Omani dialects where ج is pronounced [g]. [zˤ] or [ðˤ] and [dˤ] are distinguished in the dialects of Egypt, Sudan, the Levant and the Hejaz, but they have merged as [ðˤ] in most dialects of the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq and Tunisia and have merged as [dˤ] in Morocco and Algeria. The usage of non-native [p] پ and [v] ڤ depends on the usage of each speaker but they might be more prevalent in some dialects than others. The Iraqi and Gulf Arabic also has the sound [t͡ʃ] and writes it and [ɡ] with the Persian letters چ and گ, as in گوجة gawjah "plum"; چمة chimah "truffle".

Early in the expansion of Arabic, the separate emphatic phonemes [ɮˤ] and [ðˤ] coalesced into a single phoneme [ðˤ]. Many dialects (such as Egyptian, Levantine, and much of the Maghreb) subsequently lost interdental fricatives, converting [θ ð ðˤ] into [t d dˤ]. Most dialects borrow "learned" words from the Standard language using the same pronunciation as for inherited words, but some dialects without interdental fricatives (particularly in Egypt and the Levant) render original [θ ð ðˤ dˤ] in borrowed words as [s z zˤ dˤ].